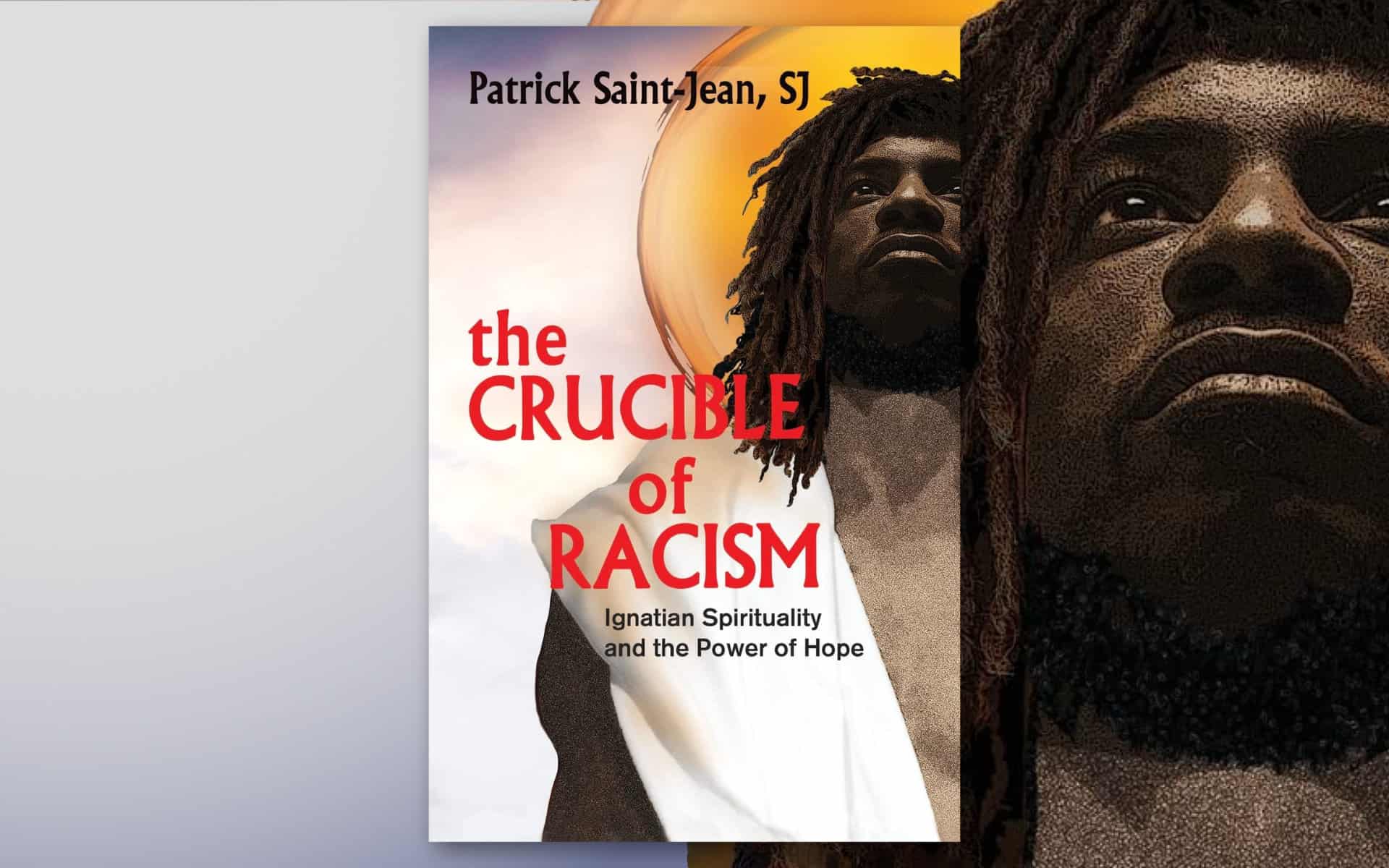

The following is an edited excerpt from The Crucible of Racism: Ignatian Spirituality and the Power of Hope, a new book from TJP contributor Patrick Saint-Jean.

“To Christians, the future does have a name, and its name is Hope. Feeling hopeful does not mean to be optimistically naïve and ignore the tragedy humanity is facing. Hope is the virtue of a heart that doesn’t lock itself into darkness, that doesn’t dwell on the past, does not simply get by in the present, but is able to see a tomorrow. “Pope Francis

Until I was eleven years old, I had never stepped inside a Catholic church. Then, when my Catholic godfather died, I attended his funeral mass. During it, I experienced a moment of epiphany that changed my life forever.

During the funeral homily, the priest looked out at us— directly at me, it seemed—and said that all of us had received a unique call from God. “God calls each one of us,” he said, “to do something special in the kingdom of heaven.” I didn’t understand exactly what the priest was saying, and yet I knew his words were somehow meant for me. I felt it in my very body.

After the service, I asked my mother about the priest’s words. She said, “The priest was talking about people who are going to be priests in the Catholic Church. You are not Catholic—so you don’t need to worry about what he said.”

I continued to think about the homily, though, and eventually, I talked to my grandmother, who was my best friend back then. She was a Southern Baptist minister, but she had also worked with a broad and varied religious community. She said, “My son, you are not Catholic, but I will pray for you, and God will provide.” The hug she gave me filled me with a sense of peace and hope.

I was born in Haiti, where the second-largest denomination (after the Roman Catholic Church) is the Southern Baptist Church. My beautiful and loving family has been Southern Baptist for generations; my mother’s family came to Haiti in 1875 to begin a medical mission and evangelize. Continuing her family’s legacy, she was the main preacher in the church where I grew up.

As a kid, I often got into fights with my mother. I was curious about everything, and so I was constantly asking questions. Often she had no answer for me; instead, she would simply say, “Well, you will have to deal with your eagerness yourself. Go to your room and pray about it.”

When it came to questions about social justice, however, she always made time for me. With care, love, and patience, she helped me understand the complexity of these subjects. Our devotion to social justice was woven into our family, and I understood that the community was an essential part of our identity as Christians. Both my parents are well versed in social ministry, and from them, I learned many things.

The person who had the strongest impact on my life, though, was my grandmother, Félicie Saint-Georges. She was my first role model, a model of love. Sharply intelligent, a nurse by profession, a Southern Baptist preacher by passion, and an avid politician and social worker, my grandmother taught me to be a man of hope. She believed that tomorrow will always be better; it is just a matter of waiting for what God will do. Equality, justice, and freedom were the themes of the songs she sang to me, and her love of community shaped my life. It inspired me to also become involved in social action and seek God in others through justice and love. I grew up believing that I was born to serve God in active ministry. But my family never dreamed where my vocation would take me.

My grandmother worked for the Haitian consulate in Paris, where she often met with various religious leaders, including Father Pedro Arrupe when he was the Superior General of the Jesuits. Father Arrupe’s passion for working with Vietnamese refugees inspired her, and she had come to love the Ignatian way because of its commitment to social justice. She had also heard Father Arrupe allude to a Christ who was not a white man; instead, said Father Arrupe, Christ looks like all of us, no matter our race, no matter our gender. Christ is each of us.

“Be open to God in everything,” Father Arrupe said. His words encouraged my grandmother to persist in her work for justice. Ignatian spirituality does not discriminate—and through its lens, she came to see more deeply that standing up for those who are racially and economically on the margins is a spiritual practice.

“Learn to see Christ in everyone, in everything, everywhere,” she taught me. Ignatian spirituality was helping her find a wider and deeper path to the Divine. Since I too was eager to learn more and follow the urging in my heart, she introduced me to her friend Father Moreau Joseph, a Jesuit who also taught in the school I attended.

Until his death in 2004, Father Moreau was my dear friend. Through him, I learned more about the Jesuit practice of finding God in everything, in everyone. Even on the path of suffering, he told me, I would encounter Christ. He showed me the way of justice, healing, and reconciliation that he had learned as a follower of the Ignatian way.

Perhaps most important, through Father Moreau’s teaching, I came to see a Christ who is not white. When I found myself in all-white settings at school, he would say to me, “Stay on the path, Patrick. Hang on. Remember Jesus was not white.” His words inspired hope in me, a hope I have needed more than ever in recent years.

Because of Father Moreau’s influence, I was eventually confirmed as a Catholic. He helped me understand that the feeling I had carried within me ever since my godfather’s funeral was God’s voice calling me to the priesthood. And all the while, my friend was teaching me more and more about the Society of Jesus.

As my friend told me more about the Jesuits, I heard God’s call for my life even more deeply. Ignatian spirituality, I sensed, would be the bridge that I would cross to connect my heart with God. It would also become the vehicle through which I engaged with the world around me.

Through the process of Jesuit formation, the lens of Ignatian spirituality has allowed me to focus more sharply on the work of justice. The teachings Ignatius left us do not create a philosophy or even a theology; instead they act as a doorway through which we can enter a new way of living in the world. Ignatian spirituality is a powerful tool in my work for racial justice, healing, and reconciliation.

Ignatian spirituality offers an alternative to the forms of Christianity that have been used to justify slavery and colonization, which, in their more modern forms, continue to be used to deny justice to the Black community. The white church has often cherry-picked its way through the Bible, ignoring scripture’s clear and consistent support of those whom society has marginalized. Meanwhile, the actual message of the Hebrew Scriptures and the message of Christ in the Gospels and throughout the rest of the Christian scriptures challenge us to build a world based on justice, equality, and love. The teachings of Ignatius of Loyola give us practical ways to respond more deeply and effectively to Christ’s call to an inner spiritual transformation that is expressed through social justice in the world.

This is not to say that this is the only spiritual tradition that supports the antiracist struggle. There are obviously many others, within both Catholic and Protestant Christianity as well as in other faith traditions, but this is my way. It is my doorway into the Divine Presence. It gives me the tools I need to do the work to which God has called me. Through the Society of Jesus, I lay claim to the identity my grandmother embodied: I am a person of possibility, a firm believer in the power of love. I am a man of hope.

For nearly five centuries, members of the Society of Jesus have been using the tools of Ignatian spirituality to lead people to Christ, promoting reconciliation and healing for the marginalized—but these same tools are freely available to everyone, not only Jesuits. Ignatius insisted that his teachings were not intended only for the clergy; they are also open to laypeople. Today, Ignatius continues to invite everyone—through their own experiences, whatever they may be—to find Christ in everything. Ignatian spirituality helps us know that God is at work, always knocking at the door of our lives. No matter where we are, God is there with us.

Included in the tools that Ignatius offers us are The Spiritual Exercises, a detailed structure for personal prayer and reflection, as well as the Daily Examen. We will spend more time with both of these in later chapters but let me say now that the Examen lies at the very heart of this book.

In my own life, the daily practice of the Examen has led me to a new perspective on my identity. When I joined the Jesuits, I also came to America, where I encountered something, I had never experienced before: racism. I learned I am a Black man—and that America, including the Society of Jesus here in this country, is white space where people of color are not welcome. This direct experience of racism became a crucible for me.

In the medieval practice of alchemy, a crucible was a container where different elements were heated to extreme temperatures in order to create an entirely new substance. For me, the racism I encountered after I joined the Jesuits generated a space of both fire and transformation, both deep pain and startling new hope. It began a process of transformation within me. As I write this book, I realize I am still dwelling within that crucible.

Recently, while talking with a friend, a fellow Jesuit, I commented that the stories that I use in this book to illustrate racism come mostly from my experiences with Jesuits in America. At the same time, I feel pressured to disguise the identities of the individuals involved in these incidents. My friend compared my difficulty to the sexual scandals within the Catholic Church. In the beginning, as the scandals came to light, the Church would not reveal the names of the men who had committed these acts of sexual violation. The underlying understanding was that by protecting the individuals, we were also protecting the Church. Then, after the Pennsylvania grand jury report, the Church was asked to release the names. As I listened to what my friend was saying, I recognized the accuracy of his comparison, and my stomach began to cramp. My head was spinning, my hands were sweating, and I felt as though I could not catch my breath. When I tried to speak, I choked. Tears sprang from eyes. My church, my own order, is still protecting itself rather than face the truth and bring renewed justice and healing into the world.

In writing this book, it is not my intention to complain about my fellow Jesuits. I know that they, like me, are imperfect human beings, struggling to live out their calling as followers of Christ, as well as followers of the path left for us by Ignatius of Loyola. I want to affirm all that is good about the Jesuits and testify to the good they do in the world. But at the same time I ask myself: Why are we not allowed to speak the names of those who have mistreated Blacks? Why do we care more about shielding the wrongdoers than we do those who spend their lives on the margins of society? Are we going to side with the Gospel—or are we going to take our stand as “Christians” or as Jesuits, seeking to protect the “good name” of those identities? If we are truly followers of Christ, won’t we follow his example and care more about those who have been abused and overlooked than we do the reputation of any group to which we belong? What would God have us do? As I wept over these questions, I knew I was once more feeling the fiery pain of the crucible in which I live.

You do not need to be Black to live within this crucible. My experience is as a Black man and as a Jesuit, so this is the perspective from which I write this book, but you may have lived within some other branch of the BIPOC (Black, indigenous, and people of color) experience—or you may be a member of the LGBTQ+ community. You may have some form of physical challenge that has placed you at the margins of society, or you may be forced to confront ageism or sexism. Regardless of your race or gender, racism and the other “isms” that have shaped your life in some way, you too are in the crucible.

This book is for us all, because Ignatian spirituality can convert this place of fire—regardless of its form—into a place of regeneration. Through Ignatius’s powerful tools of discernment, we can all—no matter what our individual experiences—come to understand more deeply what God asks of us from within this container of pain and possibility. Together, we can be transformed.

Despite the danger my skin color represents in the white spaces I move through, Ignatian spirituality has allowed me once again to live with the hope my grandmother taught me. Hope is fundamental to me; it is reinvented every day, and it underlies my thirst for justice.

As a Black Jesuit, I have learned to have hope in my brother Jesuits. I have learned to have hope for America and for our entire world. That hope, as well as my love for the Catholic Church, for the Society of Jesus, for America, and for our global community, is what has inspired this book. I write this book neither to protect nor to denigrate these institutions but because of my faith in their potential.

The Structure of the Book

As you read this book, I hope you will join me on a spiritual pilgrimage of healing and hope. In the first part of the book, we’ll discuss the nature of racism’s crucible. In the second part, we will focus on how we can apply Ignatian teachings more specifically to the work of antiracism. Finally, we will go through the four phases of Ignatius’s Spiritual Exercises. Although Ignatius divided the Exercises into weeks that can be practiced over thirty days, where each “week” represents a stage in the process of entering into relationship with God through Christ. Each stage has a different theme, and we will apply each one to the crucible of racism.

In each of these chapters, I invite you to encounter a Christ who is yearning for justice, healing, and reconciliation. I pray that in all this you will hear God’s call to you. Racism is a sin against the image of God in our fellow human beings, but antiracist work is a ministry of transformation. This is what my grandmother taught me, and this is also what I have learned from Ignatian spirituality.

We can’t take action, though, unless we can breathe, for breath is essential to our life. In fact, it is so essential that we often take it for granted. The year 2020 taught us to look at breath differently, though. That seemingly endless year of pandemic, isolation, racial injustice, and protest made us aware of one another in new ways. We could no longer ignore the very essence of our lives. We discovered that we live in what I call the Age of Breath—a time when we are all being called on to learn once more how truly to breathe.

If you enjoyed this excerpt, please consider purchasing your own copy of The Crucible of Racism: Ignatian Spirituality and the Power of Hope.

*No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher, Orbis Books.