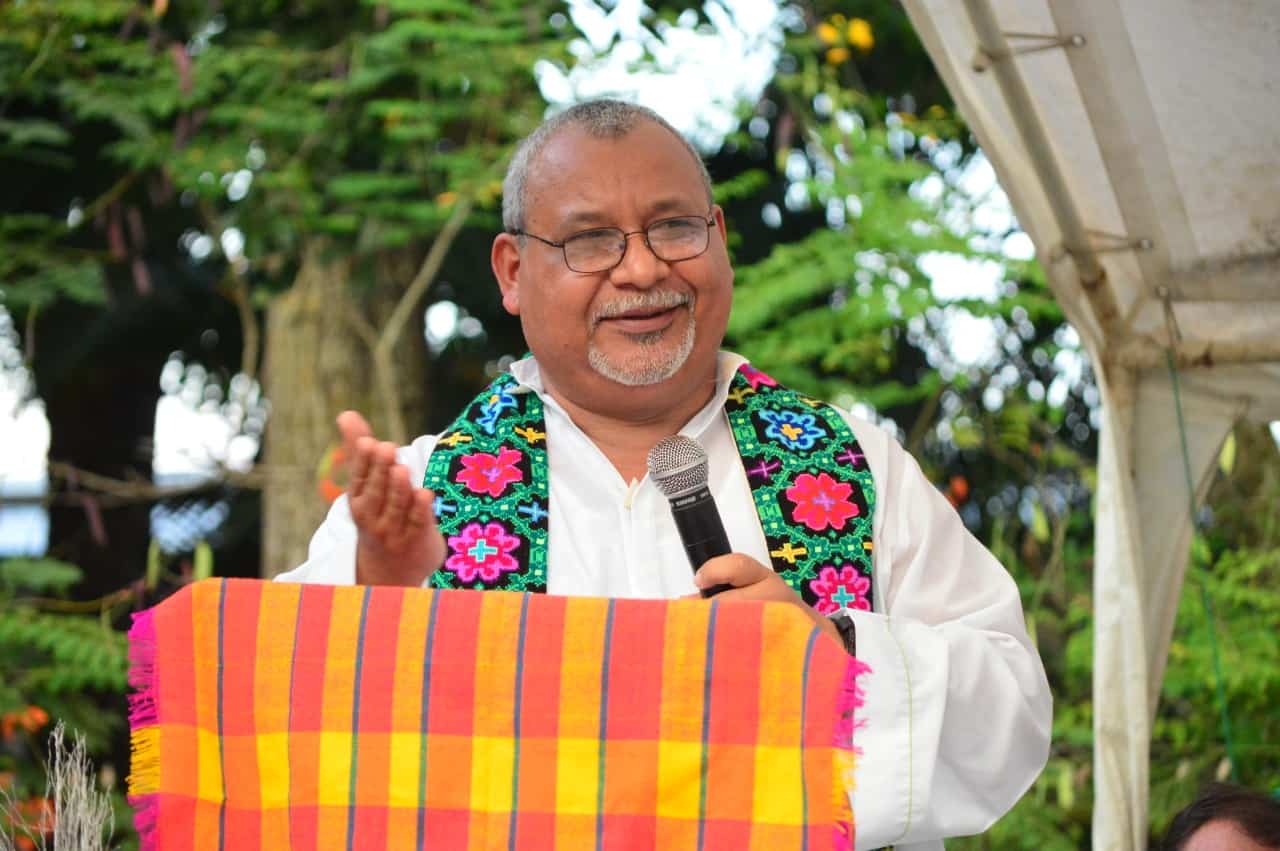

The regime of the narco dictator Juan Orlando Hernández and his right-wing National Party of Honduras fell on Sunday, November 28, 2021, with the election of the left-wing Xiomara Castro de Zelaya of the Party for Liberty and Refoundation (LIBRE). Ms. Castro secured the most votes that a presidential candidate has ever obtained in Honduran history. David Inczauskis, SJ, interviewed Fr. Ismael Moreno, SJ, in El Progreso, Honduras, about Ms. Castro’s victory. Fr. Melo is the director of Radio Progreso / ERIC, a communications and social research ministry of the Central American Jesuits.

Describe the reality in Honduras behind Xiomara Castro’s victory. What’s been going on in Honduras that led to her election?

What do we see behind the 2021 elections? We see a Honduran society that from my point of view has three ingredients of a profound crisis. The first is an economic model that permanently produces inequalities. Here in Honduras there are–at least five years ago according to a study–five people, five men, who have a fortune equivalent to the combined minimum annual salary of 2 million Hondurans. And this is increasing! It’s a model that produces inequalities, that concentrates wealth, that takes away opportunities from millions of Hondurans.

The second ingredient of the crisis is a development model based on extractivism, on exploiting natural resources, which makes the country move inevitably towards greater environmental degradation, compounded by the problem of global warming. Honduras has become one of the most vulnerable countries to natural phenomena.

And the third ingredient of the crisis is an institutional state of affairs that is moving increasingly towards ungovernability. That’s to say we have a political system that favors small groups, that’s responsible for corruption, for impunity, for the violation of human rights. These three ingredients of a crisis are behind Ms. Xiomara Castro’s victory in these elections.

In the U.S. press, Ms. Castro has been called a socialist. Is she a socialist? What are Ms. Castro’s economic proposals?

I don’t think that Ms. Castro’s political project is a socialist one, beginning with my conviction that she doesn’t have a socialist model as her horizon. Better put, she has a great desire to restore democracy, and her triumph is largely due to the deterioration that we’ve lived through in Honduras. Honduran society is sick of corruption, of impunity, of the violation of human rights, of organized crime, including high public officials connected to drug trafficking. So I don’t think she’s a socialist.

Moreover, she represents a coalition that stretches from the left that supported Mel Zelaya Rosales before the 2009 coup to the Party for Innovation and Social Democratic Unity (PINU) and other parties of the center right. It’s very hard to say that it’s a coalition that wants to move towards a socialist project. In this coalition, there are some tied to the Party for Liberty and Refoundation who come from a socialist tradition and are interested in orienting the country towards a project that they call “democratic socialism.” But I believe that Ms. Castro has neither the coalition nor the capacity to push for such a project.

The Honduran project is not ideological. It is not a political ideology. It’s about humanity. It’s about a society that has been in such extreme conditions that it’s just looking for healthcare, for education, for truly Honduran responses, for employment, for more access, especially among the youth, to a bit more dignity and to overcome such high levels of violence. Those are the basics. I think that all that about a socialist project is not real, and I don’t think it will happen in the future. We’ll have to start a debate about what’s the best political project for Honduras, but, right now, it’s not the project that matters but the necessity of recovering people’s dignity, to have work, healthcare, and education for our people.

From a Christian liberationist perspective, how can one interpret Ms. Castro’s victory? We know that the Church does not identify itself with a particular party or politician, but we also know that the mission of the Church has a political dimension. Where do the reign of God and Ms. Castro’s proposals coincide?

They coincide in the search for justice and the dignifying of Honduran society, especially the most destitute. I believe that Ms. Castro incarnates the yearning of many of us in the Church who are looking to attend to the cry of the poor. If I had to summarize, I would say that our current mission is to listen and attend to the cry of the poor majorities in Honduras. I think that Ms. Castro situates herself in that dimension. But of course the Church must maintain clear autonomy and independence from any political party and from any government because the mission of the Church is to be the critical consciousness of society and to defend the rights of the most humbled, oppressed people.

Insofar as a government attends to the cry for justice and the grievances of the poorest people, the Church can be close to its project, always without getting confused, always maintaining its independence. Insofar as a government distances itself from the societal demands of the impoverished, the Church has to become a critical consciousness, a channel for denunciations and a defender of the rights of the poorest.

Right now, I think Ms. Castro is identified with the search for justice. The Church, as a continuation of the mission to historicize the reign of God, also searches for justice. We are together, but we are not married. We are simply together in our identification with the cry of the poor.

Help us understand Ms. Castro’s religious identity and rhetoric.

Look. Ms. Castro is Catholic. Now, she is quite resentful towards church hierarchy because she has expressed that the Church closed its doors to her after the coup. In fact, for a certain time, she was not permitted inside a church building. She’s said as much in a few close circles, but she is Catholic. She has looked for closeness to the Church. She’s looked for people in the Church who would listen to her, who would heed her.

During the campaign and after her victory, Castro has spoken about LIBRE’s martyrs. Who are these martyrs? What do these martyrs have in common with the martyrs of the Bible and of church history?

The martyrs to whom Ms. Castro is referring are those people in Honduras who, for their commitment to justice, for their love of a new society, lost their lives. They were killed. They are martyrs who represent a Honduran tradition of commitment, of dedication. They are martyrs who were assassinated during the coup and after it. They have names like Berta Cáceres or Margarita Murillo here along the northern Honduran coast. They have names like Carlos Escaleras in the zone of the Aguán. They are people who had faith in others. They had faith in justice. They had faith that the future would be one of dignification.

How are these martyrs associated with those of the Bible and of church history? Well, they are associated because they had faith in humanity, faith in God, faith in justice. They were committed to social transformation. It has to do with humanity. The martyrs were not only humans. They defended the cause of humanity, and, in humanity, God is present.

Upon giving their lives or upon having their lives taken away, they were enmeshed in the church’s tradition of martyrs in which God’s cause is humanity’s cause. As the church fathers would say, where the glory of God shines, justice and right shine. Therefore, these martyrs actively or passively sought for God’s glory to shine in humanity. Therefore, there is an intimate unity between the martyrs of the people and the martyrs of faith in Jesus Christ.

We are about to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the publication of A Theology of Liberation by Gustavo Gutiérrez. In that book Gutiérrez speaks of dependency theory and dependency’s noxious effects in Latin America. Does dependency theory continue to accurately capture Honduran reality? What will Ms. Castro do to overcome Honduras’ economic dependency?

Dependency theory is a valid norm here in Honduras because dependency theory tends to present contrasts, profound contradictions in society: the development of some at the cost of the underdevelopment of others. That’s to say, the accumulation of capital is at the cost of the impoverishment of the great majorities. As long as we fail to break from that contradiction, which is a fundamental one, we will only move forward with great difficulty. The problem of justice in Honduras is that it cannot be resolved in patches. It cannot be resolved by cosmetic changes. It cannot be resolved through welfare. Why? Because the Honduran problem is a response to structural roots producing violence, producing inequalities, and dependence is intimately connected to poverty. As such, dependency theory says that development produces underdevelopment. In that sense, it’s still relevant here in Honduras.

Ms. Castro, in as much as she hits on these dynamisms that produce development and underdevelopment, will be putting in practice a profound process of transformation. I think that throughout this century what we’ve had here in Honduras have been mere patches. It’s been welfare that has hidden the deep reality. And this means accumulating conflicts. If I had to summarize the political history of Honduras, I’d say it’s a history of continual processes that accumulate conflicts. Ms. Castro’s task is not to continue accumulating conflicts but to expose these conflicts in order to get to the bottom of what’s producing millions of people without work, without opportunities, with wealth concentrated more and more in fewer and fewer hands. To break with this is Ms. Castro’s task as well as that of those who are committed to backing this process of transformation.

Generally, Radio Progreso has offered a very positive interpretation of Ms. Castro’s victory, but is there anything of concern? What of her politics deserves criticism?

She’s yet to put policies in place, but still one can perceive some concerns. One is the amount of family members in her government. Her son went on campaign with her. Her other son was with her the entire campaign. Her daughter ran for Congress. Her husband was president, and he’s her presidential advisor. That’s worrying. It’s an expression of nepotism. We must be on alert. For example, there’s a serious issue. According to the Constitution of the Republic, her daughter, who won a seat in Congress, should not be a congresswoman. Ms. Castro should do her part to make her daughter step down. It’s what’s best for the common good, for their image. It’s what’s best all around.

Since arriving in Honduras a few days ago, I’ve noticed that many folks are especially hopeful. Most are abuzz with happiness. What’s happening in Honduras?

What’s happening is that we’ve been carrying for so many years an enormous burden: disenchantment, anxieties, fear, uncertainty. I believe that, with the electoral results that gave the win to Ms. Castro, people feel that a big weight has been lifted. Though she’s yet to do anything, we feel that something different is happening. Something has changed. We feel lighter. And that generates happiness. We have a right to life, for our happiness to be prolonged. So we have to just come out and say it: we are a happy people after a long bout of sadness.

What needs to happen is for that happiness to keep its feet on the ground. We must not forget that the reality of violence, misery, and unemployment remains a wound in contemporary life and that these politicians of today are the same as those of the past. They can play us dirty, including those close to Ms. Castro. That’s why it ought to be happiness but with firm feet, happiness but with a view towards the future, happiness but with a critical word.

It’s now for us in this early stage to be of critical support. We should never conspire with the government. Even if it achieves much, we should not conspire. For example, the new government has asked for my collaboration, and I have given it. I am going to support but also maintain my autonomy and that of my team. Why? Because our role is always to be the critical consciousness of society and of the established power. The present danger is to conspire with a power that would later make us lose our freedom, make us lose our identity. And so, happiness, with our gaze placed critically on the future and with our feet placed in the reality that we have to transform and from which we will develop proposals and demand that our elected officials respond to the cry of the poor.

This abbreviated interview was translated into English from the original Spanish by David Inczauskis, SJ.