COVID-19 is not the first pandemic of our lifetime. But we’re certainly acting like it is.

Missteps, misinformation, and pandemic-fatigue have propelled the virus into a brutal new wave of infections in the United States and elsewhere around the world. Have we learned nothing from the last eight months?

Or how about the last forty years?

The AIDS epidemic emerged in 1981 when the CDC published the first official reporting on what came to be known as AIDS (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome). Since then, nearly 76 million people have become infected with HIV, the virus that causes AIDS, and a staggering 33 million people have died from AIDS-related illnesses. Those are statistics that almost make the coronavirus look tame by comparison with more than 60 million cases and counting, and 1.5 million deaths.

What can we learn from nearly 40 years of the HIV/AIDS pandemic? What can it teach us about our way forward as we continue to confront the coronavirus pandemic? Turns out, a great deal.

*****

Both HIV/AIDS and COVID-19 have infected millions of people around the globe and millions have died from these diseases. Narratives of disinformation and clinical confusion exacerbated the spread of both these diseases: Do masks really make a difference for the spread of COVID? (Yes!) Does AIDS only affect gay men? (No!)

Stigma can travel hand-in-hand with disinformation. When coronavirus first hit the United States, many Americans cast a stigma on people of Asian descent, with outright hate crimes or by insidiously calling it the “Chinese virus.” While those sentiments have largely subsided in the mainstream, AIDS activists continue to challenge the stigma that AIDS is a disease for people who are “morally inferior,” casting judgement on high-risk groups like gay men or people who inject drugs. When this stigma ostracizes individuals and stifles public action, the inherent dignity of human persons is violated, and lives are critically endangered.

Admittedly, there are marked differences between HIV/AIDS and COVID-19. COVID results from an airborne virus that spreads quickly and easily. If symptoms manifest, they appear between 2-14 days after exposure to the virus. For the majority of patients, their bodies can overcome the virus and develop antibodies with minimal medical intervention.

In contrast, HIV/AIDS is primarily transmitted through the exchange of bodily fluids during sex or by sharing needles when injecting drugs. It develops much slower in the body than COVID, and it can take years for symptoms to manifest. Unlike with COVID, our bodies are unable to overcome HIV and there are no antibodies that resist it. Heavy medical intervention in the form of antiretroviral treatment (ART) has made it possible for people to live decades with the disease. But there is still no cure and no preventative vaccine.

*****

A cure for HIV remains elusive, but we can learn a lot from forty years of fighting the HIV/AIDS pandemic. Allow me to offer three important lessons from HIV/AIDS that should shape our way forward with the coronavirus pandemic.

-

Prevention before infection effectively eliminates the spread of the virus.

Only someone who has HIV can pass it on to someone else. And once a person is infected with HIV, there is no cure. Thus it is critically important to prevent infection in the first place.

Drugs that reduce mother-to-child transmission of HIV prevented a staggering 1.4 million estimated new HIV infections from 2010-2018. And a groundbreaking trial in 2011 revealed that people taking ART are 96% less likely to transmit the virus. In other words, the medication provides a double benefit of treating the virus and cutting transmission rates. National and global responses to HIV/AIDS have recognized the twin need for addressing treatment and prevention.

The lesson for fighting coronavirus is that measures that prevent infection in the first place are critically important. Wearing masks, social distancing, quarantining after exposure, and even widespread lockdowns are not simply suggestions that we can choose to abide by or disregard. These are critical methods for preventing infection in ourselves and others.

A terrifying characteristic of COVID-19 is how easily it spreads, including through asymptomatic carriers. Too many people have lowered their guard because of asymptomatic cases. This is a disregard for personal safety. It is a disregard for the common good. And this is precisely how COVID-19 is spreading so effectively: people are unwittingly sharing it with neighbors, family members, and co-workers. One person might be asymptomatic, but they can pass the disease to someone who ends up on a ventilator. Or dead.

Preventing infection in the first place can eliminate the spread of the virus. Adopting preventative measures like wearing masks and social distancing is everyone’s responsibility.

-

The “terrain” matters.

Louis Pasteur, the French biologist and chemist who discovered the principles of vaccination (and pasteurization, his namesake) is said to have noted on his deathbed: “The virus is nothing, the terrain is everything.”

Understanding the biology of viruses like HIV and coronavirus is not sufficient for curtailing the damage it can do to a human population. We have to look beyond the virus itself and examine the “terrain.” The terrain comprises the economic, political, social, and cultural factors that result in differential susceptibility to a virus. These factors are largely under our control. Too often, the combination of these factors results in structures that oppress people, violate human dignity, and heighten inequality, which constitutes social sin.

A variety of economic, political, social, and cultural factors have complicated the global response to HIV/AIDS.

Economically, extreme poverty has been both a cause and consequence of HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa. On the one hand, lack of resources for prevention and treatment have driven the region to the highest AIDS rates in the world. On the other hand, reduced life expectancy and the depletion of the labor force have drastically decreased economic productivity.

Political leadership has shaped national responses to HIV/AIDS, often with dire results. For example, the former President of South Africa, Thabo Mbeki, denied the link between HIV and AIDS and cast skepticism on Western pharmaceuticals. In the early 2000s, he limited the availability of live-saving medication that resulted in an estimated 330,000 lives lost along with 35,000 babies born with HIV during the first half of his presidency.

Social factors like the lack of access to healthcare services and education further drive the AIDS pandemic. Getting tested, accessing sexual and reproductive health care, and learning prevention strategies are all methods for reducing HIV rates.

Cultural factors like gender roles and agency in sexual relationships have heightened women’s susceptibility to contracting HIV. Women now account for nearly half of all people living with HIV worldwide, and 59% of new HIV infections in sub-Saharan Africa.

The lesson for fighting coronavirus is that our response needs to be attentive to the economic, political, social, and cultural factors at play. To date, President Trump’s leadership in responding to the pandemic has contributed to the United States being the country hardest hit by the disease. In comparison, the government’s quick and attentive response in countries like South Korea and New Zealand has led to astoundingly low rates. Developing a comprehensive National COVID-19 Strategy in the United States, based on lessons learned from the National HIV/AIDS Strategy, would be an obvious starting point and is already long overdue.

Insufficient initial investments in testing and contact tracing, politicizing preventive measures like mask wearing, emphasizing individual liberties over a sense of the common good: these factors constitute our current terrain. This terrain is allowing the coronavirus to flourish in our midst.

The spread of the virus has exposed existing inequalities. In his latest encyclical, Fratelli Tutti, Pope Francis writes: “If everything is connected, it is hard to imagine that this global disaster is unrelated to our way of approaching reality, our claim to be absolute masters of our own lives and of all that exists.” On Thanksgiving Day, he called for a deeper societal conversion in an op-ed for the New York Times: “what is revealed is what needs to change: our lack of internal freedom, the idols we have been serving, the ideologies we have tried to live by, the relationships we have neglected.”

Yet rather than responding collectively in order to change what has been revealed, many have begun to normalize COVID deaths as though they are unavoidable and unpreventable. But that’s just not true. An adequate political response combined with social and cultural shifts can dramatically alter the trajectory of the virus.

Because the terrain matters!

-

Marginalized communities are disproportionately affected by the terrain.

There’s an old African American aphorism: “When white America catches a cold, black America gets pneumonia.”

The United States has stabilized and begun to reduce the number of new HIV infections every year, but minority populations continue to be disproportionately affected. In 2018, Black Americans accounted for 13% of the U.S. population, but 42% of the roughly 38,000 new HIV infections. Latinos make up 16% of the population, but account for 27% of new infections.

On a global level, low- and middle-income countries similarly suffer more acutely from HIV/AIDS. East and Southern Africa, in particular, has borne the brunt of the pandemic, with over half (54%) of global cases of HIV despite this region accounting for only 6% of the global population. The regional explosion was initially fueled in part by the high costs of treatment. It took until the early 2000s for generic drugs to cut prices for developing countries.

The lesson for fighting coronavirus is the urgent need for a coordinated response for marginalized communities. The false narrative that “COVID doesn’t discriminate” obscures the reality. Black people have been dying from COVID-19 at twice the rate of white people. Latinos are nearly three times more likely to be infected than white people. Native American populations, like the Navajo nation, have been hit particularly hard, and so have immigration detention centers and prisons.

The reason these communities have higher rates is not because members of these communities failed to take the pandemic seriously. In his article titled “Stop blaming Black people for dying of coronavirus,” Ibram X. Kendi cries out: “Black people are not to blame for racial disparities. Racism is to blame.” Heightened susceptibility is a direct result of the terrain, infected with racism, that has worked dramatically against minority groups. Socio-economic factors that existed long before the arrival of COVID have resulted in minority groups living in more crowded conditions, working in essential fields, confronting bias in medical care, and suffering from discrimination and institutionalized racism. COVID-19, much like HIV/AIDS, is merely exposing these long-festering wounds.

Marginalized communities are at higher-risk because of the terrain. A preferential option for the poor and vulnerable compels us to respond by resolving structural inequalities and prioritizing these communities going forward.

*****

The prospects for our future with COVID-19 are plagued by uncertainties. Sky-high infection rates in the United States paint the picture of a bleak winter. But promising results from vaccine trials offer rays of hope. Even still, a vaccine won’t address the underlying societal forces in the terrain that have been exposed. Where we go from here depends on how we choose to respond.

The lessons of nearly forty years of history with HIV/AIDS should shape our way forward. Prevention before infection remains fundamental to stopping the spread, and we need to take individual and collective action to adopt recommended preventative strategies. The terrain of economic, political, cultural, and social factors needs to be addressed head-on, beginning with a national COVID-19 strategy that addresses imbalances in these factors that facilitate the spread of the virus and hinder our response. Marginalized communities that are disproportionately affected must be prioritized going forward in regards to regular testing, distribution of preventative equipment, and access to medical care, including a vaccine, along with addressing the structural injustices that perpetuate unequal health outcomes.

On this World AIDS Day, let these lessons also serve as a reminder of the work left to be done with HIV/AIDS.

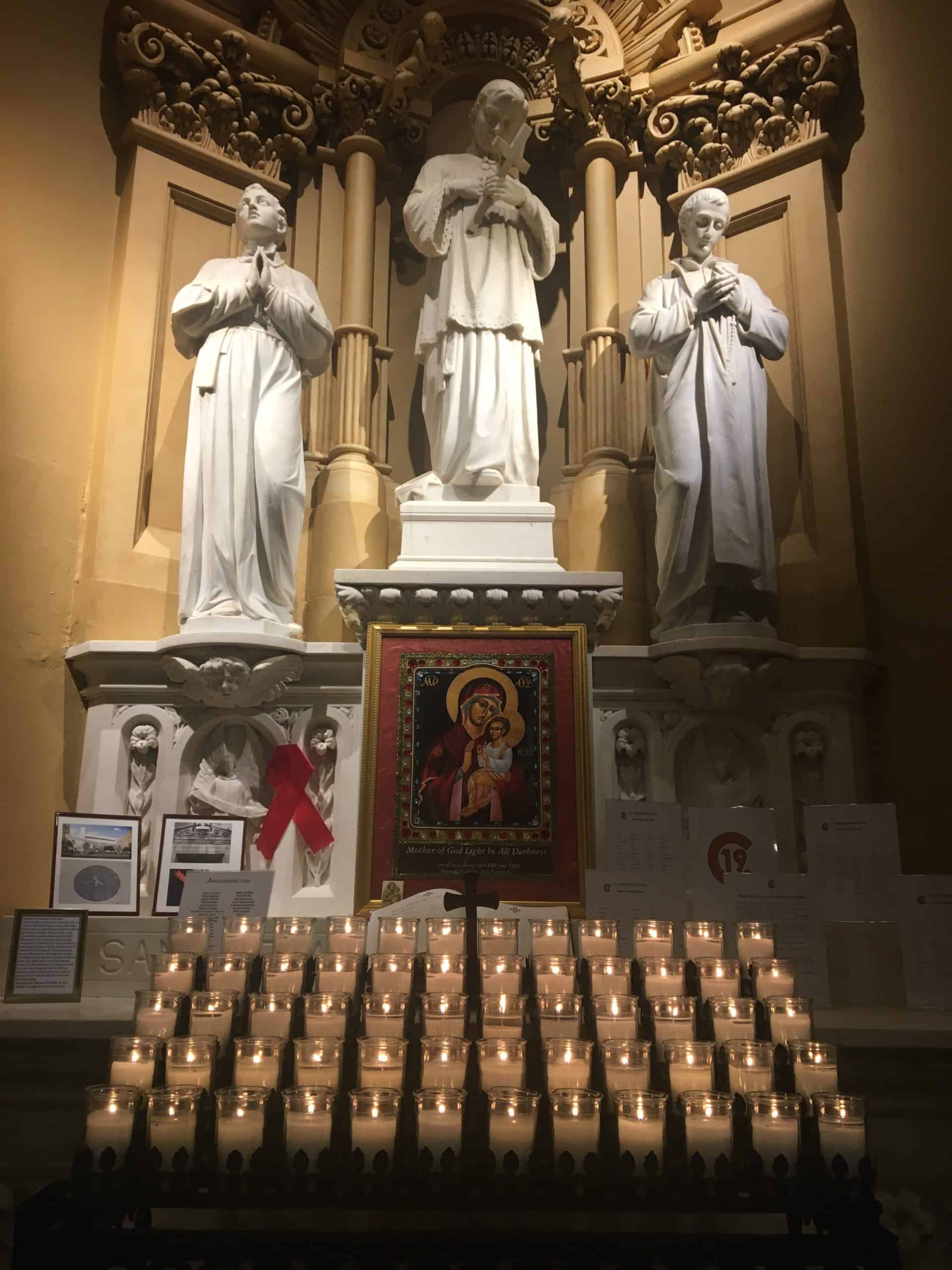

HIV/AIDS Altar of Remembrance at the Church of St. Francis Xavier in New York City, which now includes a memorial for victims of COVID-19.

The early stigma around COVID may have faded, but stigma around HIV remains prevalent and continues to slow progress in ending the pandemic. Several COVID vaccines are in the pipeline with promising results, but there is still no vaccine for HIV and no cure. There have been tremendous global investments in the COVID response, but funding for HIV/AIDS has been declining, with low- and middle-income countries receiving decreasing international assistance. Lockdowns and border closures due to COVID have impacted the production and distribution of ARTs, which could lead to half a million additional deaths from AIDS-related illnesses in the months ahead.

Following the lessons learned by the HIV/AIDS pandemic can help us emerge from the COVID-19 pandemic. And as we move forward, let’s not forget the other pandemic that continues to ravage our world.

//

Cover image courtesy of FlickrCC user Alachua County.