“I don’t love my country. I just can’t love the United States.”

That’s what a man next to me said on a plane from San Juan, Puerto Rico. He went on to share about his move to San Juan, his love for Puerto Rican culture, his hatred for Donald Trump, his shame for mainland America’s quasi-colonial public policy, and this last statement:

“I don’t love my country…and I know it breaks my parents’ heart. But I just don’t.”

It was sad to hear, and I couldn’t explain why. I kept wondering what made this so sad?

The question that came to me on the plane—why is this so sad?—eventually turned into another one: what do I love when I love my country?

Despite being an American citizen all of my life, the more I think about this question the more my thoughts turn to Mexico. And family.

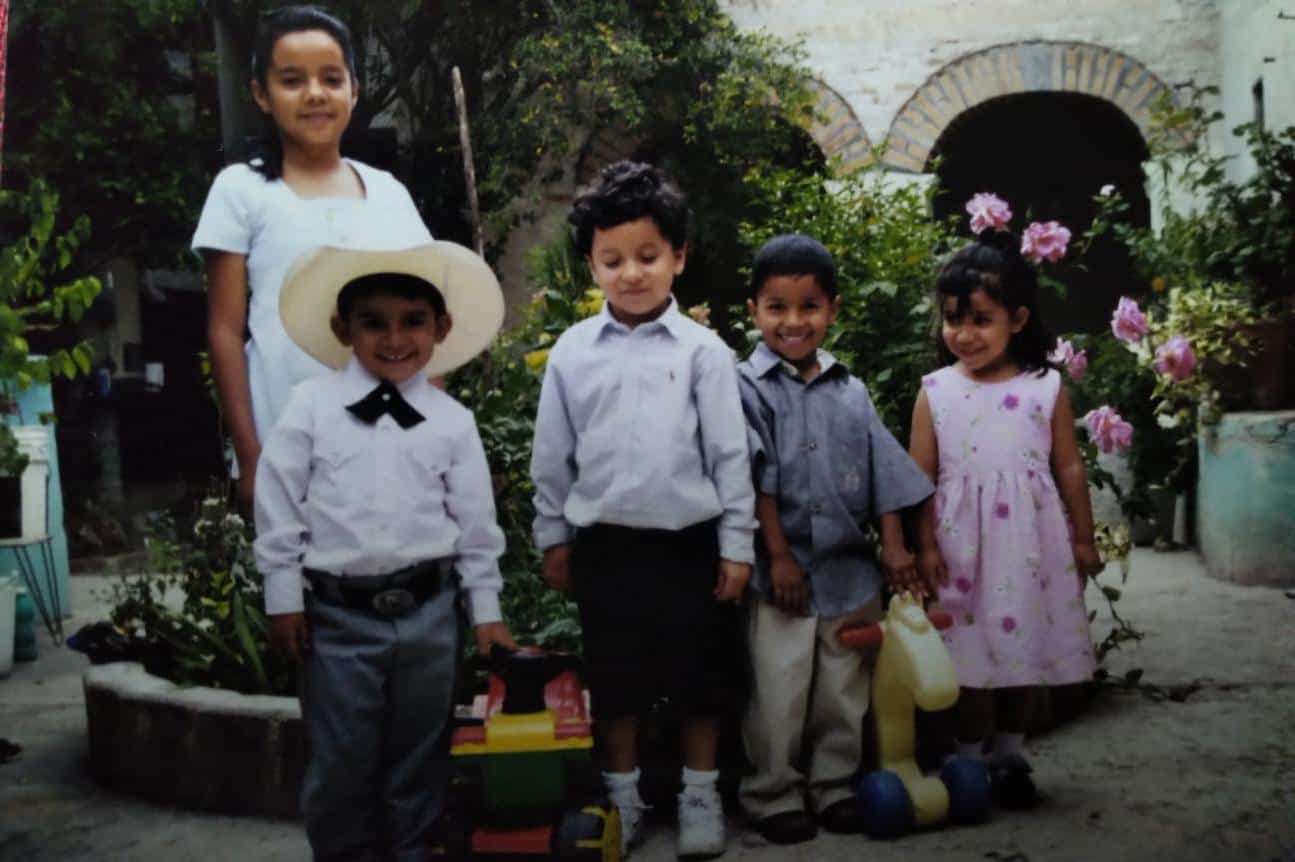

Most of my family don’t live in the United States. My parents are from San Luis Potosí, an eight hour car ride from where I grew up on the border. It’s in their hometown where I was surrounded by my extended family, where I lived out the best parts of my childhood. It’s where I really felt like a kid. This place where I’ve never lived is home to a lot of the simple joys—like playing soccer with my cousins—that warm my memory, regardless of however few times they happened or however far each instance was from the last.

Admittedly, there’s an ambiguity: whenever I was in Mexico, I was the American. I recall an instance where a family friend heard me speak and asked my dad, “why does he talk like that?” Fair enough. On that subject, the movie Selena expresses something a lot of people feel: “Anglos will jump all over you if you don’t speak English perfectly. Mexicans jump all over you if don’t speak Spanish perfectly.” Because even on the border success is tied to speaking perfect English, it’s now my main language. And despite the residual feeling of inadequacy when speaking Spanish, it doesn’t dampen my love for my family’s country. Why should it?

My family, my childhood, the place where I was baptized and received the Eucharist for the first time—that’s what I love when I love Mexico. It altogether doesn’t really matter to me if most Mexicans consider me unambiguously American. It’s a type of love that hasn’t diminished even though it’s been years since I’ve been back. My time there has sunk into the lodges of my childhood memory, stitched unto a part of me that no one other than God and myself can see.

At the risk of downplaying everything imparted to me while growing up in the Rio Grande Valley, the part of myself that loves Mexico feels like something hidden beneath the layers of American culture that’s accrued unto me. An analogy for why I feel heart-tied to Mexico is what the ancients called substance (οὐσία). It refers to what’s most basic and underlies all the accidental and unessential properties of a thing. Substance is that which grounds me, on the side of being as opposed to having.

Appropriating substance to talk about love for country means that it’s ultimately underneath anything I’m able to put into words, especially into a Spanish that always sounds wrong to me or an English that I feel some guilt for speaking with ease.

I do believe there’s something so beneath us, inside of us, that we can never fully expose to the world, even if we wanted to. And it points to something beyond love of country.

To get to the point: there would be something precious missing from me if I didn’t love the country where my parents are from. The love that I’m describing isn’t just a love for a land, a body politic, but for family extending both ways generationally: both the love received from the ones that raised you and the love you give to the family who will long outlive you. To love family is to love the first community you ever encounter. For me, love of country is at the service of a bond that ties relatives across time. It’s why the book of Genesis seeds the birth of Israel within the story of a family, and why the Gospel of Matthew opens by listing a genealogy that culminates with Jesus.

Admittedly, it wasn’t ruminating on Biblical narrative or puzzling over Aristotle’s Categories that helped me think through what constitutes this elusive love for country. It was Chance the Rapper. It was hearing him cover Hamilton’s “Dear Theodosia (reprise).” The song presents love of your country as a way of loving your children. It points to a love of country that’s deep-down a promise: I’ll stay with you so long as I have God-given life, and I’ll do anything to make this place your home. In the context of the musical, I think the song reveals a love for country that’s inextricable from the love these men have for their kids.

From the nebulous love of country we’ve arrived at the astonishing love of a parent for a child, and what it means to accept that love, too.

What’s so sad about not loving your country is that belonging to a people, culture, and nation are a part of what it means to be human, so much so that it was a part of the life of Jesus, something the Lord took up in becoming human. And in my life, it’s been a stepping stone for coming to know Him. As a Jesuit mentor said to me recently, “it’s not like God loves you apart from your history.” The family that raised me and the culture they raised me in was the way God decided to weave my story into his story, meaning it’s how Christ enfleshed himself into my life.

And that’s worth holding onto—no matter what country you’re from.