Are you ready to give up the wheel?

Self-driving cars are coming. In fact, they are already here. A self-driving truck transported beer in Colorado. In California, they are logging literally thousands of miles. Car manufactures and major tech companies like Google, Uber, Tesla, and, most recently, Apple are competing to stay on the cutting edge of this technology.

It’s no longer a matter of “if,” but rather “when” the streets and highways of our world become populated by self-driving machines with people and cargo as their idle passengers.1

Technological change usually comes upon us whether we like it or not. But even a feeling of inevitability shouldn’t excuse a lack of reflexion. Technological progress isn’t an inherent good. It brings with it much more than that.

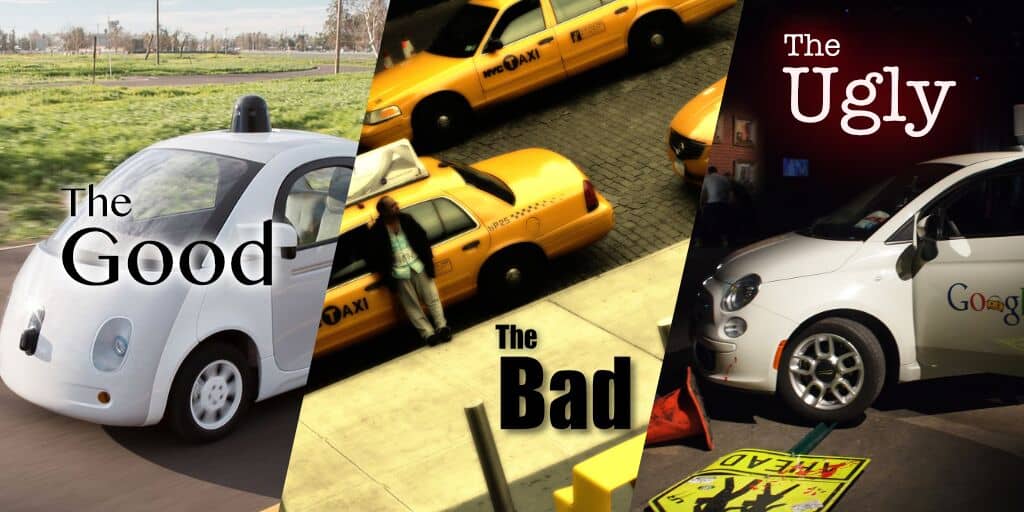

Let’s take a look at self-driving cars, and THE GOOD, THE BAD, and THE UGLY.

Self-Driving Cars: THE GOOD

Over 37,000 Americans and 1.3 million people globally die every year in automobile accidents. Those are staggering numbers. It’s the ninth leading cause of death globally (just ahead of HIV/AIDS), and it’s the only non-disease entry on the top ten list.

Have you ever thought about the power that’s in your hands when you drive a car? It’s actually quite remarkable that we entrust millions of people across the world (you and me included) to navigate two-ton metal machines speeding at 60 mph between buildings, pedestrians, and other vehicles. We’re not even that good at it.

While human driving error is not the sole cause of all 1.3 million deaths, some estimates put the number of accidents committed through human error as high as 94%. Self-driving cars might not be able to eliminate all driving fatalities, but couldn’t they lower the number?

It seems pretty safe to assume that self-driving cars would at least outperform a drunk driver or a texting teen, which would go a long way to saving lives on our roads.

Almost a third of fatal traffic accidents in the U.S. are caused by drunk drivers (around 10,000). Additionally, cell phone use and texting have led to a spike in accidents related to distracted driving. According to the Center for Disease Control, distracted driving kills more than eight people and injuries more than a thousand people each day in the U.S. alone. The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration estimates that 80% of traffic accidents and 16% of traffic fatalities are related to distracted driving.

And so we arrive at THE GOOD. While further arguments could me made for efficiency gains,2 financial benefits,3 and even the prospect of creating transportation independence for the blind or disabled, let’s just stick with the biggest argument in favor.

THE GOOD: Self-driving cars can save lives!

*****

Self-Driving Cars: THE BAD

Think about your most recent drive: did you pass any delivery trucks? A local bus? Maybe a taxi or two? All those vehicles are piloted by paid employees. And lots of people make a living by driving- millions of people, in fact.

Roughly 3.5 million people in the U.S. make their living from driving vehicles around.

NPR made noise a couple of years ago when they published a map showing the most common job in every state, and truck drivers dominated by leading the way in 29 of the 50 states. While these statistics don’t paint the clearest picture, the fact is that roughly 2.8 million Americans make a living by driving trucks.

On top of that, there are taxi drivers. New York City alone has over 13,000 medallion-licensed taxi drivers, not to mention all the Uber and Lyft employees (errr…contractors?). Across the country, the total number of U.S. licensed taxi drivers and chauffeurs is around 190,000, while Uber claims the engagement of around 160,000 drivers. Throw in half a million school bus drivers and around 170,000 transit bus drivers, and you get the picture. Lots of jobs.

So we arrive at THE BAD. Let’s skip over the periphery jobs that could also be lost,4 and excuse the fact that the job statistics are U.S.-focused.5 An argument could also be made for the negative health effects of safer driving that would worsen the shortage of organ donors.6 But there is one argument against self-driving cars that is the most prominent.

THE BAD: Self-driving cars will eliminate jobs!

Self-Driving Cars: THE UGLY

What about accidents that do occur? What about accidents that are unavoidable?

Results have shown that human error has played a primary role in almost every reported accident with a self-driving vehicle, but the increased use of self-driving vehicles will inevitably involve more accidents, including fatal ones.

In May of last year, the fatal crash of a self-driving Tesla in Florida applied the strongest brakes to the self-driving car movement and tempered enthusiasm. In the incident, a tractor trailer made an ill-advised left turn into oncoming traffic, and the white side of the trailer against a brightly lit sky wasn’t picked up by the vehicle (nor the driver who was still behind the wheel). The self-driving car did not “see” the tractor trailer. So who is responsible for this accident? The rider? The manufacturer?

This was the first case of a fatality from an automation error. But a bigger ethical question looms. How will we program self-driving vehicles to confront situations where an accident is inevitable? What if the outcome varies based on different maneuvers?

Let me illustrate by example:

Car A and Car B are two self-driving cars that are side-by-side on a highway. An inattentive child darts in front of the car on the left (Car A). The car’s computer notices the child, and calculates the following options:

1- Swerve left to avoid both the child and the other car, and head into the median where Car A’s rider has a 60% chance of survival.

2- Swerve right to avoid the child, but collide with Car B from the passenger side, where Car A’s rider has a 80% chance of survival but Car B’s driver has just a 30% chance of survival.

3- Apply the brakes swiftly but maintain a straight course. The child has a 1% chance of survival, Car A’s rider now has a 99% chance of survive, and Car B won’t be impacted.

A human driver who has to confront such a situation wouldn’t have time to calculate the odds, and would have to react instinctively. Given the frightening outcomes, we would be quite sympathetic regardless of how the driver responds.

But with a self-driving car that can run calculations and make decisions in fractions of a second…how would we want it to respond?? That is to say: how would we program it?

Should it swerve left to assume the lowest odds at killing someone, although the highest risk would fall on the car’s rider/owner? Should it swerve right to protect a young child, even if it risks adult riders? Should it stay the course to protect the safety of its owner above all others?

An ethical dilemma like this should give us pause. The more that we allow technology to interact with us in the world, the more we force technology to confront ethical dilemmas. In the case of self-driving cars, we are literally placing a potential killing machine (a 2-ton vehicle) in the control of a computer.

We have reached THE UGLY. Let’s pass over the murky question of the environmental impact, and the legal uncertainties of potential lawsuits, and go to the clear winner.

THE UGLY: the ethical puzzle of self-driving cars is complex and controversial.

****

Have we given sufficient thought to these factors? Have we weighed THE GOOD, THE BAD and the UGLY?

I’m afraid not.

That is to say, I am literally afraid that we have not considered all of these factors, especially not THE UGLY.

Why? Because there is one “GOOD” that I did not address: the earning potential for manufacturers of self-driving cars.

In the U.S., we are in a seven-year streak of growing sales in the auto industry, with 17.6 million cars sold in 2016. As for the global level, hold your breath. In 2010, we passed the one billion mark for the number of cars on the roads. Projections suggest that the total could reach 2.5 billion cars by the year 2050 (!!!). That’s a LOT of cars; that’s a LOT of cars to be sold. And if the wave of the future is self-driving cars, that includes a lot of cars to be replaced.7 In other words: $$$.

Here’s the bottom line: the financial incentives for automakers and tech companies is enormous. Literally billions of dollars in profits are at stake.

Let this give us pause to reflect.

- THE GOOD of reducing traffic fatalities and accidents in general is valuable and a tremendous human good.

- THE BAD of lost jobs is frightening, as we continue to confront the loss of millions of lower-skilled jobs to new technology (in which we basically always favor the technological gains to the preservation of the jobs).

- But THE UGLY, especially in this case, is something that deserves even more thought and reflection. A self-driving car is not on an equal level as all other forms of technology, especially when it comes to life and death ethical choices.

While your iPhone might be a real time-suck, it’s not going to make a decision that could take someone’s life. Drones have the power to kill, but we still haven’t granted them the ability to choose their own targets (and for good reason). With self-driving cars, there is no avoiding it. A two-ton vehicle speeding among other cars and people will inevitably make contact. Ethical choices will have to be embedded in their programming.

We cannot allow the inevitability of technological advance to impede us from reflecting on the risks at stake. We cannot allow profit-driven corporations to play up the benefits of new technology while diverting attention from the unavoidable ethical dilemmas contained within. What values guide our policies on the programming and development of self-driving cars? Ethics? Or financial gains?

We have to give more careful consideration to all aspects: THE GOOD, THE BAD, and THE UGLY. Only then can we make informed decisions about how to create and control the technology that will become a part of our future.

The time to reflect is now, while the wheel is still under our control.

- Commercial self-driving vehicles could be available as soon as 2021. ↩

- Efficiency is a clear winner with self-driving cars. With the car in control, riding along could be more akin to taking the train or riding public transportation (without the discomfort having to squeeze into a crowded space). Perhaps you could use that time to catch up on emails, play with your kids, make a few phone calls, or read a book. Traffic flow would also be more efficient through the precision of self-driving cars, which would result in fewer traffic jams and less time wasted in gridlock. Plus for shipping purposes, a self-driving truck could run all day and all night. So yes, self-driving cars would bring efficiency gains. Now, whether these efficiency advances are inherently good or not is more debatable. ↩

- A good argument can be made that self-driving cars would save money. Fewer accidents (not just the ones that cause fatalities, but all accidents) means less money spent on repairs, maintenance, and medical bills. Insurance prices would be expected to drop as the risk of accidents declines. Fuel efficiency could be increased, saving a few bucks at the gas station as well. Nonetheless, this new technology will come with a hefty price tag for the first the first couple of generations, so it’s probably too early to bank on this yet. ↩

- On top of all those who make a living by actually driving, some other periphery jobs could also be lost, most notably auto repair workers if the number of car accidents declines drastically. Valet parkers would become as obsolete as pay phones and Blockbuster video. ↩

- The global number of people employed in these industries is really difficult to estimate, which is why the cited statistics are from the U.S. But if you’ve traveled abroad to large urban centers, anecdotal evidence alone suggests that the global total of taxi, bus, and truck drivers is staggeringly large. ↩

- Thousands of Americans already die every year while waiting for organ donations. And that shortage could be exacerbated by safer self-driving cars: one in five organ donations comes from the victim of a vehicle accident. ↩

- A strong argument could be made that self-driving cars will eventually drive down the number of personal automobiles bought and sold (and I recommend this article for the argument laid out), but there will still be millions of self-driving cars manufactured if/when the movement takes off. An early entrant in this market could stand to gain a great deal in profits. ↩