The final score was a dismally boring 14-2. Our hometown Oakland A’s were creamed by the storied Boston Red Sox in a sparsely attended game, in their ugly, concrete stadium. The game – late in the season for our non-playoff team – didn’t count for much. But my community had gathered together for the first time that evening and this outing meant a great deal for us – a chance to get to know each other a little better before beginning another year of studies.

I live with a good number of international men, and the rules and process of America’s pastime eluded them. In truth, the rules of baseball elude me most times, too. Infield fly rule? Fielder’s choice? How is what is plainly a hit ball is not recorded as a hit? I saw him hit it! And when did instant replay become a thing in baseball? Still, I could follow along better than most, having grown up with a father and older brother who obsessively watched the Mets (another historically dismal franchise) and who could spout off sports trivia as if it were a full-time profession.

There’s more to baseball, of course, than just watching the game and always has been. On TV, there are advertisements to contend with as well as color commentary from some-less-than-colorful commentators. 1

But nowadays in the stadium itself, there are lots of gimmicky things happening – things you only used to see at minor league ballparks or stadiums for the most local of local semi-professional teams. The athletes themselves participate in pre-recorded (and mindless) polls: Adele or Taylor Swift? Kids run the bases between innings.

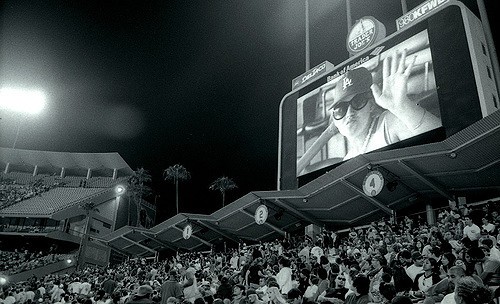

From the comfort of my uncomfortable seat, I took in all of these frenetic happenings there on the Jumbotron, that huge TV screen that hangs over this stadium and in stadiums all over the world, projecting live video, stats and figures in bold colors and flashes of light. The Jumbotron in Oakland may be the largest one of these I have ever seen.

There are on-camera interviews with long-time season ticket holders, people who – like my dad – root for their team through ups and downs and who drive long distances to take in a game in person. And there is public recognition of couples, one of whom chose to spend their 50th wedding anniversary with their beloved spouse watching their beloved team get shellacked. And sometimes, when there isn’t anything hokey planned for between innings, the cameramen just scan the crowd, and unsuspecting, anonymous people find themselves suddenly projected on that huge screen.

The reaction is almost always the same: an arm from someone out of the shot begins pointing at the Jumbotron. The person on whom the camera is focused turns and sees him or herself projected and magnified on said Jumbotron and their mouth drops open. (They’re always surprised.) They smile a small half-smile. As their recognition intensifies, they and the people surrounding them begin to dance or point, or otherwise break out into some never-before-seen full-bodied freedom. Hips are swung. Fingers are raised. Teeth are flashed. The camera cuts to another group of unsuspecting persons and the unchoreographed but familiar mayhem unfolds again in real time on a really big screen. The next inning brings more of the same – uninhibited people flailing and smiling, laughing and pointing. And the inning after that, too.

More than the information it displays, more than the flashes of light that could elicit a seizure in some, the Jumbotron has some sort of magnetic pull for spectators in the stadium. It’s a point of reference for the game’s stats, to be sure, but more and more the Jumbotron is the point of reference for something more: a sort of anonymous yet embodied awareness of self and others. The Jumbotron shows us something familiar in a surprising way. People see themselves there on the huge screen, but it provides more than just an exhilarating 15 seconds of fame.

How to explain the Jumbotron? Perhaps by saying that it provides an opportunity to remember that one exists at all, anonymous there in a temporary community of other anonymous souls, uninhibited and carefree, even if only for the briefest of moments during meaningless games. There I am! Look at me go! Now you!

–//–

The cover photo, from Flickr user Ben Nyberg can be found here.

- I grew up suffering with Tim McCarver’s banterless banter on WWOR, Channel 9 in New York. The rest of the nation was subjected to him only later in his career. Lucky you. ↩