Apple’s announcement that it would offer a free three-month trial of its new music streaming service was met with great celebration in late June. The company’s simultaneous announcement that they wouldn’t pay artists during the trial period was met with considerably less glee, especially among musicians. Most prominently, Taylor Swift called out Apple, saying the lack of pay was unjust. Probably sensing a possible PR debacle, Apple quickly changed course and agreed to compensate artists during the trial period.

In her letter, Swift summarized the issues this way: “This is about the new artist or band that has just released their first single and will not be paid for its success. This is about the young songwriter who just got his or her first cut and thought that the royalties from that would get them out of debt.”

This was not the first time the country queen turned pop icon weighed in on the issue of streaming music. Swift previously scolded Spotify for their inadequate artist pay. Likewise, if you follow the band CAKE on Facebook, you’ve seen their regular posts on this issue. They and many other artists have two overarching concerns: first, record labels get almost all of the profits from sales, and artists get close to nothing from streaming royalties.

Macklemore and Ryan Lewis even comment on these issues in the song “Jimmy Iovine.” The well-known duo points out that the record label gets almost all profit for the music, and conclude the song by saying they would “Rather be a starving artist than succeed at getting f**ked.” Much like Swift, they are asking an important question that goes beyond simple economic self-preservation.

The debate over artist compensation is not new. It stretches back at least as far as ripping and burning CDs from the public library, and trading music over Napster or LimeWire. At the heart of the fair compensation debate is simply this issue: most of us want artists to create music for us, but we don’t want to pay them for their skills.

This raises serious questions about workers’ rights. Are these people fairly compensated for their labors? Is their creativity unjustly used to enrich others because of lacking protections? To put it simply, they are asking us: “How much do we value the work of others?”

***

Wages and compensation are hot button issues right now, and not just in the music industry. Folks are realizing just how little our minimum wage can actually buy us. (Check out this great Living Wage Calculator to learn more.) The Fight for 15, labor unions, and many other groups have been pushing for an increase in the minimum wage. Consider also the populist support Bernie Sanders is winning. Much of this stems from his insistent demand for higher wages. Wages, however, are only one facet of the American landscape around workers’ rights.

You might be wondering, “Workers rights? Those aren’t an issue in the U.S. We already went through that part of our history!” We might assume American workers have it better than our foreign counterparts. Many say that U.S. workers should just stop whining.

But American workers aren’t whining. They’re making demands that accord with their rights as workers and as human beings. Though we’ve already gone through a difficult and dangerous part of American labor history, we’re currently repeating it.

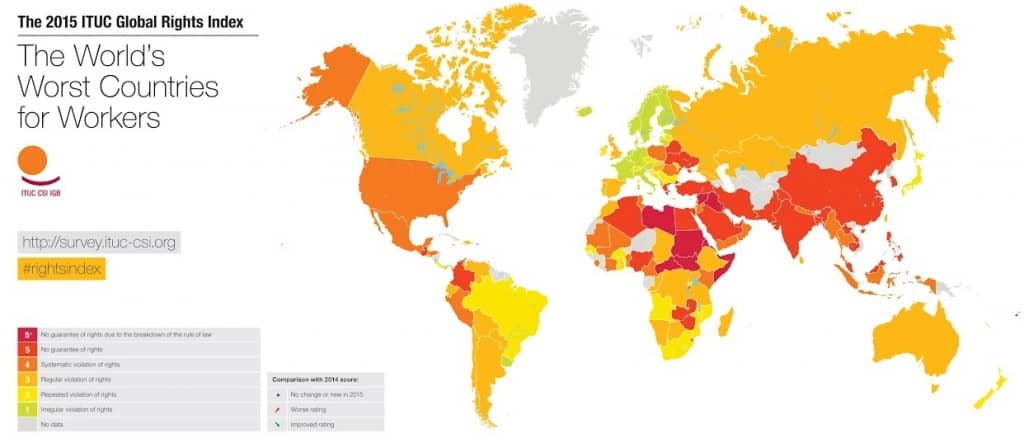

To put it bluntly, America sucks when it comes to workers’ rights. A report by the International Trade Union Confederation1 states that on a scale of 1 to 5+ (1 being best, 5+ being places with little rule of law), the U.S. sits in category 4. This means that we systematically and regularly violate workers’ rights. Who do we share that category with? Mexico, Honduras, Indonesia, and 24 other countries – not very good company.

The ITUC Global Labor Rights Map (used with permission).

The University of Iowa Center for Human Rights reported in 2012 that thirty-four percent of U.S. employers have fired workers for attempting to join or organize a union. The Institute for Southern Studies found that half of all factories facing unionization threaten to shut down and move elsewhere; three of four companies hire anti-union firms to run campaigns; and nine of ten companies force workers (legally) to sit through anti-union propaganda sessions.

UCLA reports that in Los Angeles alone, employers steal $26.2 million from their workers every week. Moreover, when LA workers filed claims against employers, even 83% of those who won their case never saw a penny. This wage theft overwhelmingly affects women and people of color.

These are problems we desperately need to address, even if they don’t regularly pop up in our social media feeds.

***

Catholics have a beautiful tradition of supporting workers, both in articulating social teaching and standing alongside workers as they seek their rights. The Jesuits in St. Louis, to cite just one example, used to run a worker organizing school. But, if we’re honest, Catholics have been part of worker abuses in terms of squashing workers’ rights.

Several Catholic (and Jesuit) universities, hospitals, schools, and diocese have launched anti-worker campaigns. Some outsource services like janitorial staff to avoid paying a fair wage and insulate themselves from calls for just treatment. The Sisters of St. Joseph of Orange health care system in California, for example, fought to prevent the organization of thousands of service employees. Charges of spying and worker intimidation were brought before the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB).

Universities have likely garnered the most attention within the Catholic world for their anti-union efforts. Seattle University gained unwanted notoriety for their efforts to quash a union campaign of adjunct faculty. Duquesne University used its religious affiliation as reason for rejecting unionized teachers. The Duquesne administration stated that its religious affiliation exempted it from NLRB rules, and has reportedly made veiled threats to those leading the pro-union campaign.

Our Catholic institutions’ treatment of workers is simply unacceptable. We must ask ourselves, as our colleagues at America recently did: which side are we on?

***

As states and the federal government continue picking apart workers’ rights, it is imperative that our Catholic institutions demonstrate what it means to support employees. In “Economic Justice for All,” the U.S. Catholic Bishops state, “the Church employs many people; it has investments; it has extensive properties for worship and mission. All the moral principles that govern the just operation of any economic endeavor apply to the Church and its agencies and institutions; indeed, the Church should be exemplary.” 2 Basically, the bishops are saying that Catholic institutions have a lot of fiscal clout. Not only should the Church apply moral behavior to its economic activities (such as employment), it needs to be stellar in supporting economic justice. That includes a full array of workers’ rights, such as openness to unions, a fair wage, and paid leave.

Organizations like The Kalmanovitz Initiative for the Working Poor and Just Employment Policy have been pushing for Catholic institutions to respect and advocate for workers’ rights. It is time for all our institutions to get on board. After all, as a highly visible proponent of workers’ rights (i.e., the pope) said in Laudato Si’ that “We require a new and universal solidarity ”3. Perhaps like Swift, Pope Francis’ demand for justice will cause us to rethink labor rights in the United States.

In her letter to Apple, T-Swift says, “Three months is a long time to go unpaid, and it is unfair to ask anyone to work for nothing.” She’s absolutely right. It’s wrong to expect anybody to go without compensation for their work.

Perhaps Swift’s point could also be said of Catholic institutions and wider labor questions in the U.S. Moreover, Catholic organizations would do well to consider another point she made in writing to Apple: “But I say…with all due respect, it’s not too late to change this policy and change the minds of those in the music industry who will be deeply and gravely affected by this.”

Not too late, in other words, to do the right thing.

–//–

The cover image, “TS (2),” is by Flickr user Sonny Li.

- One might justly question whether a trade union league is biased. The ITUC is actually a special representative to both the United Nations and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. ↩

- Economic Justice for All, US Conference of Catholic Bishops, 1983. Emphasis added. ↩

- Laudato Si’, Paragraph 14 ↩