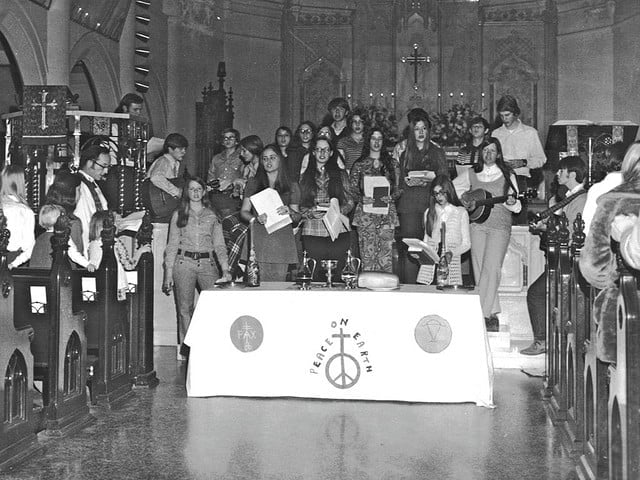

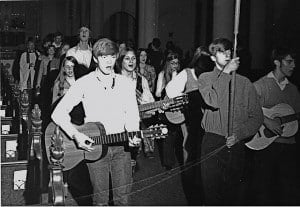

Over at Commonweal Cathleen Kaveny has a great piece about the Church in the 1970s. Plenty of people lament that decade as the “silly season,” as she calls it, replete with “sharing, caring, and felt banners.” About the musical revolution of the time, she tells us: “I do not remember much about [my] confirmation ceremony itself. I am pretty sure we sang ‘On Eagle’s Wings.’ Don’t judge—it was the ’70s!”

Ah yes, “On Eagle’s Wings.” The much-derided staple of the folk mass phenomenon that came out of the liturgical reforms of the 70s.1 It was the music that defined singing-at-church for a generation – my generation specifically. Where chant and organ music reigned for centuries prior, guitars and tambourines became de rigeur!2 A quick look through the song books from the time will tell you that the new style marked a turn back to scripture for Catholic hymnody. For some, the music to their ears was the wailing of Gehenna, while for others, it became, well, a treasure in – wait for it – Earthen Vessels.

But I submit the following: Even though the St. Louis Jesuits got their start in the 1970s, they were not the truly great revolutionaries in modern liturgical music. No, I say the greatest experiments came from the 1960s. As evidence, I give you the following, any which I dare you to trot out on an upcoming Sunday:

Exhibit A: Anything on this website.

Exhibit B: Peter Cetera (yes, that Peter Cetera) with The Exceptions and this groovy Rock ‘N’ Roll Mass from 1966 (great news, the old translation works once again!):

Exhibit C: The Electric Prunes Mass in F Minor from 1968:

Both of those groups came out of the psychedelic and acid rock styles of the decade. They pushed the boundaries of modern music with long solos and experimental guitar riffs at the same time a Church was trying to push out of its own boundaries. Stylistically they had their roots in the blues and jazz musical styles of African American culture, so if that’s the case, let’s go right to the source, or in this case, the soul of it all: Mary Lou Williams, the First Lady of Jazz, who Duke Ellington described as “soul on soul.” A piano virtuoso who worked with all the greats of her genre, Mary Lou Williams took a hiatus from music to live in Paris, where she converted to Catholicism and became a pioneer in a new genre of religious jazz; her magnum opus is Mary Lou’s Mass from 1969, which is Exhibit D:

Newsweek called the score “an encyclopedia of black music, richly represented from spirituals to bop to rock.” This is Williams’s “Music for Peace,” a landmark recording which addressed many of the social ills of the 1960s and 70s. It is perhaps the most openly religious jazz recording made at that time. In her own words, it is “Music for the Soul.”

******

BONUS TRACK!

Because Mary Lou Williams is so exquisite3, and because her conversion was facilitated by a Jesuit (in fact, she was eventually managed by a Jesuit!), here’s Mary Lou’s adaption of the prayer attributed to St. Ignatius Loyola, the Anima Christi:

******

- For the story of how folk music came to the Roman Catholic liturgy, check out Keep the Fire Burning, by Ken Canedo. ↩

- Full disclosure: I was in a folk-music quartet with my dad and two family friends for much of my teen years: my dad on guitar, myself on the keyboard, and smooth four-part barbershop harmonies, appearing every week at the 5:30pm Vigil Mass. ↩

- Her sacred pieces on Black Christ of the Andes are worth listening to and even praying with; I take them with me on every retreat. ↩