For those of you who enjoyed the debut post for TJP’s Catholic Writing Series, we’re glad you’re back for more. Just to recap, last week we talked faith and fiction with Nick Ripatrazone, an up-and-coming author from New Jersey.

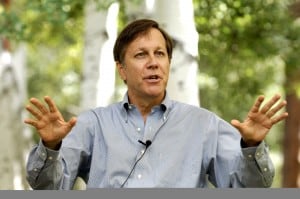

This week’s featured author has, let’s say, already been through the “up-and-coming” stage of his career. His works have long been familiar finds on library and bookstore shelves. Dana Gioia – renowned poet, critic, and former Chairman of the National Endowment for the Arts – was kind enough to do an interview with us at the last minute.

Gioia’s CV boasts a lengthy list of works and accomplishments. His 1991 essay, Can Poetry Matter?, generated so much conversation that it quickly became part of the modern canon of literary criticism. His fourth and latest collection of poems, Pity the Beautiful, was published by Graywolf Press in 2012. And if you’ve been keeping abreast of the recent conversations about Catholic writing, you will probably have run past his recent essay in First Things Magazine – an essay which featured in my conversation with Nick Ripatrazone last week. Gioia is also the mastermind of a number of national initiatives to foster consciousness of and love for poetry in the American public. If you’re at all curious about these initiatives, or about his life and work, his website will tell you all you need to know.

So thank you, Dana, for your work. And thank you for the interview. As for you, dear reader, if you’ve never read Gioia’s poetry, a piece from Pity the Beautiful follows the interview.

Cheers, folks, and let’s keep the conversation going.

_____________

JH: In your recent essay, “The Catholic Writer Today,” you show that for various reasons, Catholic writing doesn’t enjoy the public prominence that it had a half-century ago. How much of this is attributable to the writers themselves (or the dearth of writers), and how much is attributable to other entities—the Church, secular culture, or the demands of publishers?

DG: There is no single cause for the decline of Catholic literary culture. The reason my essay was so long was that the situation is complicated. The decline resulted from half a dozen converging trends– both inside and outside the Church. Internally, there was the assimilation of educated Catholics into secular society, the lack of support for the arts by the Church, the confusion in the Catholic community following Vatican II, the decline of interest in culture by the Catholic media as it became increasingly obsessed by politics, and the failure of Catholic universities to celebrate and champion our literary heritage. These trends occurred as American intellectual life first grew more secular and then turned increasingly anti-Christian. Meanwhile in the broader society there was the steady erosion of print culture—the magazines, newspapers, and publishers which had traditionally supported serious writers. This erosion probably affected Catholic writers disproportionately since they appeared to be out of sync with both the cultural and commercial mainstream.

JH: But what about the writers? Is there now a dearth of Catholic writers compared to the post-war era?

DG: I don’t think we have a dearth of writers. What we have is a dearth of opportunity and recognition. There are significant Catholic writers. But most of them have had to make their own way in the secular literary world with little support from the Catholic subculture. Young Catholic writers today face great difficulties in getting published, reviewed, supported, and employed.

The central theme of my essay is the current invisibility of Catholic artists in American culture. There are few practicing Catholics who are visible as artists in the mainstream culture. I listed about half a dozen established writers who are recognized as Catholics by the literary media. (Of course, there are many more who are not widely recognized, and there are others who keep their faith private.) It seemed paradoxical that the nation’s largest religious and cultural minority had almost disappeared from cultural life. I was trying to understand the complicated situation of Catholic writers today in a culture where they lack recognition and support from within the Church and hostility or indifference in the broader arts world.

JH: If you are exploring the current situation, why spend so much time looking at American literary life seventy years ago? Why such nostalgia?

DG: In order to explain the current situation, I had to go back to the period after World War II in which there was a great explosion of the Catholic literary imagination. Comparing the current situation to the period of Flannery O’Connor, Katherine Anne Porter, J.F. Powers, Brother Antoninus, Thomas Merton, and others helped clarify matters. The sheer size, diversity, and distinction of American Catholic literary life then is astonishing. And it shows how diminished Catholic literary culture is today.

JH: John Henry Newman once wrote that “the heart is commonly reached not through reason but through the imagination.” You also say that Catholic writing as such has more to do with presenting a Catholic imagination rather than presenting “holy” or theological topics.

DG: Newman put the matter exactly right. I don’t think most people come to God (or most other core beliefs) through rational argumentation. They usually do the reasoning afterwards to explain to themselves and others why they believe. We experience faith, as we do almost everything else in life, holistically. We feel it with our emotions, intuition, and imagination as much as with our intellect. We even experience with our physical bodies.

The power of art is that it speaks to us in the fullness of our humanity. When the Church loses that capacity, it loses it ability to speak to most of humanity in its natural language. Theological arguments don’t even convince theologians to change their minds on a topic.

JH: Do you consider yourself a Catholic poet or just a poet who happens to be Catholic?

DG: I don’t see much distinction between the two categories. I’m a Catholic, and I’m a poet. The two identities have to be connected in an artist.

I’m not a devotional poet. I have no interest in converting anyone in my poems or explaining theological principles. My ambition is simply to write as well as possible—to create poems that are beautiful, moving, memorable, and true. Poetry is a form of song, not a branch of philosophy. Having said all that, however, I understand that, as a Catholic, my sense of existence reflects my Catholic worldview, no matter what the overt topic of the poem.

JH: Who are some contemporary authors who, in your opinion, present the Catholic worldview particularly well?

DG: I’ll be happy to give you a list, but let me complain a bit first. Catholics have neglected their own cultural traditions. The most common response I got to my essay was that readers had no idea that there were so many prominent American Catholic writers in the mid-twentieth century. Ironically, most of these writers were better remembered by secular readers than by Catholic ones. There is an alarming narrowness and staleness in the official Catholic modern canon. People read Chesterton, O’Connor, Percy, Waugh, Greene, and Tolkien (usually with some C.S. Lewis on the side to be ecumenical). These are all major writers, but they represent only a fraction of our tradition. Some Catholic journals devote at least half of their literary coverage to those eight writers, the youngest of whom was born in 1925, all of whom are dead, and only two of whom were Americans. The Catholic literary world often seems disconnected from contemporary writing. Too many editors and critics seem spellbound by nostalgia. No wonder current Catholic authors feel abandoned.

There are also significant Catholic writers who remain unknown to the Catholic literary subculture. A good example is the poet and critic Frederick Turner. I’ve never seen any Catholic critic mention him—though probably James Matthew Wilson has since he seems to know everything.

Turner is not only a prolific and talented poet; he is also the most interesting theorist of the concept of beauty. He is the one contemporary who can stand comparison with Maritain, although Turner’s views grow out of different philosophical and scientific assumptions.

JH: That’s one name, but go ahead and give us a list. Who else do you think represents the Catholic literary tradition at its best?

DG: The greatest Catholic poet of the last century was almost certainly Mario Luzi who died in 2005 at the age of 90. He was greatly admired by John Paul II who commissioned him to write a Good Friday meditation. He is a modernist in the manner of T.S. Eliot. Imagine an Italian equivalent of Four Quartets. His work is profoundly Catholic in its Augustinian vision of our existence. I have hardly met anyone in the American Catholic literary world who has read him, although his work has been available in translation for half a century.

Probably the greatest Catholic poet alive today is the Australian Les Murray, a bold, versatile, and prolific writer. His work has remarkable scope. I rarely see him mentioned in the U.S.—at least in Catholic journals. Despite his penchant for controversy—not a bad thing in a poet—he is also probably the most highly regarded poet in Australia. Why isn’t he more widely read and discussed by American Catholics?

JH: How about some contemporary American writers?

DG: Tobias Wolff, Ron Hansen, and Alice McDermott seem to me the three best living Catholic writers in the U.S. Each in a different way is profoundly Catholic. McDermott explores the sociological and psychological world of Catholics. Hansen writes spiritual narratives, only some of which are overtly Catholic in their subject. Wolff is almost never overtly religious, but his work is deeply Catholic in its moral concerns. Gene Wolfe is a major talent in fantasy and science fiction. Richard Rodriguez is a brilliant essayist. I think these five writers all have a plausible claim to posterity.

If we move into the world of cultural Catholics, then there is a much larger group to choose from— Cormac McCarthy, Don DeLillo, John Guare, John Patrick Shanley, Rhina Espaillat, X.J. Kennedy, even George R.R. Martin. But that seems to me a different literary tradition. There is a great essay waiting to be written on the differences between observant and cultural Catholic writers.

The real issue for me, however, is that there are surely fine young writers we haven’t heard about because they haven’t been reviewed, anthologized, or even perhaps published. How can these writers develop their potential in a cultural vacuum?

JH: Your essay has generated a huge response. Have you learned anything from the letters and commentary?

DG: I’ve been very fortunate. The response has been overwhelming positive.

There have been a few predictable complaints that I neglected to mention one or another Catholic writer. Meanwhile two commentators claimed there had been no decline in Catholic literary life– thereby denying the very premise of the essay. Given the huge and immediate response to the piece—something quite rare for a serious literary essay these days—it seem safe to say that most readers agree with my premise that there is a problem.

The most interesting criticism the essay received came from a Protestant, Alan Jacobs of Baylor. He speculated that the reason that Catholic literary culture had declined was that the generation of O’Connor, Porter, Percy, and Powers represented an unrepeatable historical event—the explosive moment when educated Catholic writers first entered the cultural mainstream. I hope he’s wrong, but his notion is certainly worth pondering. Maybe it was the American Catholic equivalent of El Boom.

What I mostly received was a steady stream of articulate and often passionate testimonies from Catholic writers, readers, and teachers who felt that they had almost no home in contemporary literary life. I was astonished by the longing, frustration, and desolation these letters contained. I hope my essay has done a bit to remedy that situation. Catholic artists need to reclaim their rightful place in American culture.

_________

The Angel with the Broken Wing, by Dana Gioia

from Pity the Beautiful, Graywolf Press, 2012

I am the Angel with the Broken Wing,

The one large statue in this quiet room.

The staff finds me too fierce, and so they shut

Faith’s ardor in this air-conditioned tomb.

The docents praise my elegant design

Above the chatter of the gallery.

Perhaps I am a masterpiece of sorts—

The perfect emblem of futility.

Mendoza carved me for a country church.

(His name’s forgotten now except by me.)

I stood beside a gilded altar where

The hopeless offered God their misery.

I heard their women whispering at my feet—

Prayers for the lost, the dying, and the dead.

Their candles stretched my shadows up the wall,

And I became the hunger that they fed.

I broke my left wing in the Revolution

(Even a saint can savor irony)

When troops were sent to vandalize the chapel.

They hit me once—almost apologetically.

For even the godless feel something in a church,

A twinge of hope, fear? Who knows what it is?

A trembling unaccounted by their laws,

An ancient memory they can’t dismiss.

There are so many things I must tell God!

The howling of the damned can’t reach so high.

But I stand like a dead thing nailed to a perch,

A crippled saint against a painted sky.