If some the the hype around neuroscience is correct — we may never pray the same way again.

If some the the hype around neuroscience is correct — we may never pray the same way again.

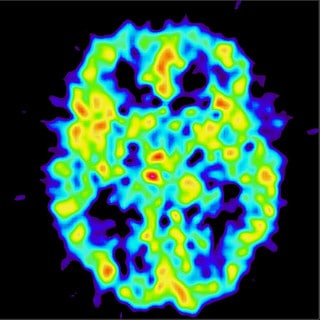

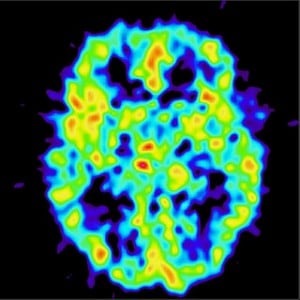

That’s one of the conclusions we might leap to from reports like NPR’s “Is This Your Brain On God?” Some research suggests that there’s a “God spot” in the brain, a region that tends to be active in people with belief in a higher being. Presuming that such a region exists and could be well described, what difference might this make in our understanding of prayer? Or, for that matter, what difference might neuroscience make about understanding everything? If we really understand how the brain works will that change the way we think about morality, self-identity, God, etc.? Will we be forced to throw away the previous understandings and adopt much better neuro-understandings?

Religion is not the only traditional area of human endeavor being investigated by neuroscience. Adding “neuro-” to anything these days is very much in vogue in the popular and scholarly scientific press. There are stories of “neuroeconomics”, “neurolaw”, “neuroethics”, and the list goes on. Many an optimistic article has been published about the promise of these new neuro-fields.

The common thread of all the neuro-disciplines is that neuroscience will revolutionize our understanding of the human world (and maybe the divine world). In the midst of the revolution some old ways of thinking must be cast aside. This is the Copernican revolution of the mind, or at least that’s the story. Roger Scruton summarizes the point well:

“[Must] our own way of understanding ourselves … be replaced by neuroscience, which rejects the whole enterprise of a specifically ‘humane’ understanding of the human condition?”

Scruton answers forcefully in the negative. His reason? Neuroscience answers fundamentally different questions than economics, sociology, philosophy, or theology. Yes it’s true that all those things in some way involve the brain, but understanding brain structures only goes a small way to understanding how the mind interacts with the world.

While I’m more sanguine about the importance of neuroscience in human self-understanding than Scruton, I take his basic point.1 Imagine trying to explain a pianist playing a Rachmaninoff Concerto. What is the best way to explain this? Well…the pianist must use her hands to play. The physiology of her hands definitely shapes the way pieces are both written and played. So if I understand how hands work I will understand the Rachmaninoff Concerto, right?

Let’s return to the example of certain parts of the brain “lighting up” during prayer. The brain is necessary for prayer much like the hands are necessary for playing the piano. Knowing what patterns emerge in the brain during prayer tells us something.2 It certainly doesn’t tell us everything. Knowing that a certain region of the brain lights us during prayer tells us nothing about, say, the existence of God. The brain is just one component of the prayer as the hands are just one component of playing a concerto. To wax philosophical: the brain is necessary but not sufficient to explain prayer and a host of other phenomena.

Neuroscience is important and, if I may geek out for a sec, intensely cool. I read a fair amount of neuroscience in my philosophical work and often find it illuminating, at least when its spotlight is aimed at the right things — it casts more light on our knowledge of neurons than our knowledge of our souls.

— — —