What if God loves us as we are? And God calls us to something higher?

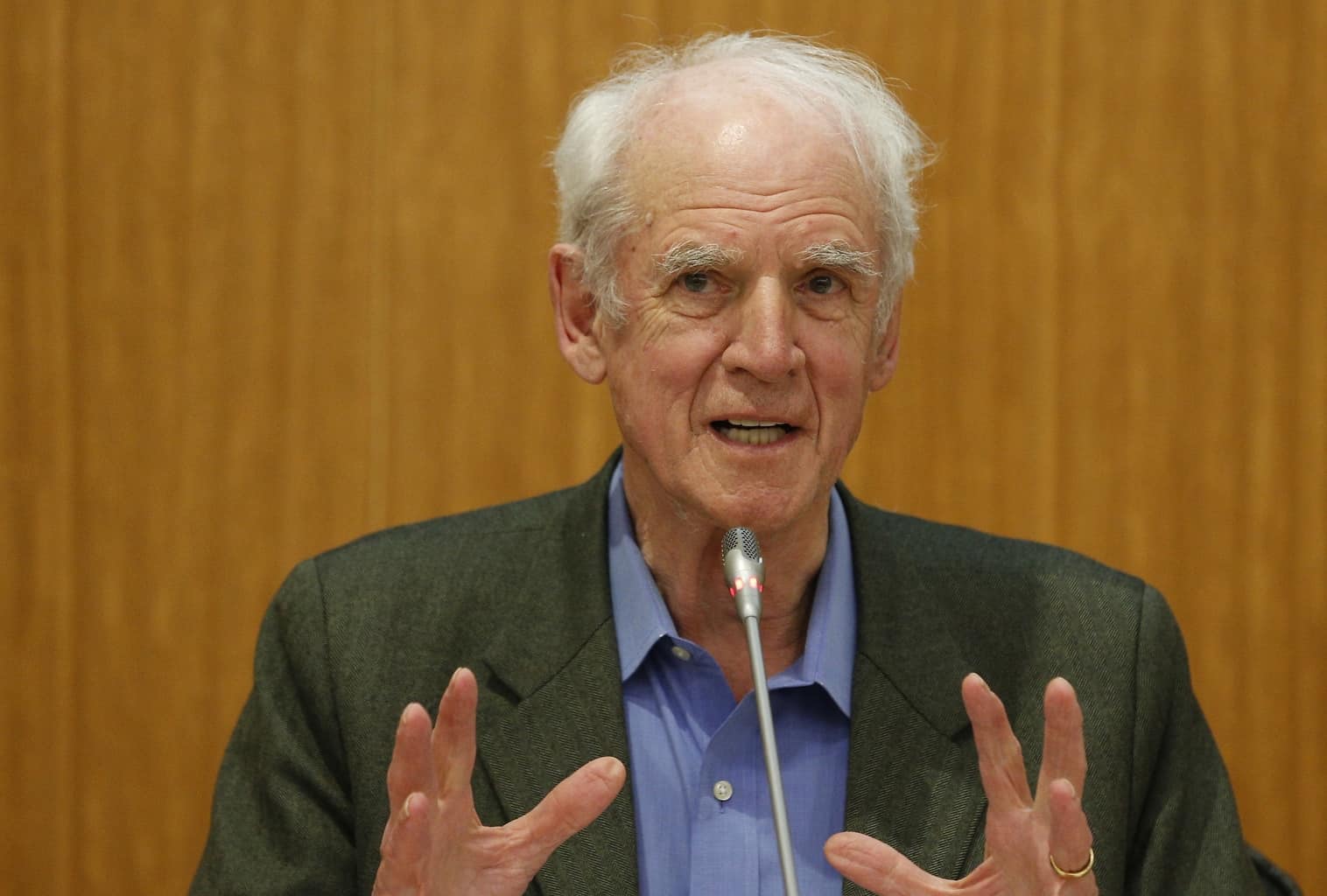

These might seem like odd questions to address to a great philosopher and social theorist, but I propose they are good ones to bring to Charles Taylor. Taylor is a scholar whose work not only attracts widespread attention from academics beyond his academic speciality, but also remains remarkably rooted in the lived experiences of his time.

It’s this second part that compels me to raise spiritual questions to an academic philosopher. Because I believe Charles Taylor has something to say about them.

Taylor has renewed his fame for his 2007 book A Secular Age, and it’s a book worth reading. In it, Taylor offers a rich account of religion and its place in the modern world. Perhaps most importantly, he offers a view of secularism as a condition where all modes of belief—including unbelief—are equally questionable and fragile. We no longer live in an age of unquestioning faith, if that ever existed, but we also no longer live at a time when atheism can claim the high ground, as at moments during the Enlightenment.

It’s how Taylor describes the Christian life that is of particular note for me. According to Taylor, Christianity animates us in two ways: it calls us to accept high goals, but also to sanctify the ordinary. Taylor speaks of an equilibrium “between the demands of the total transformation to which the faith calls to, and the requirements of ordinary ongoing human life,” (44). In other words, Christianity calls humans both to self-fulfillment and self-transcendence.

Tensions and equilibria are tricky things, and their twists and turns play a leading role in Taylor’s book. For how does one define and live out high spiritual aspirations while also offering a path to transformation that does not crush its adherents? How does a religion that calls us to be perfect like its founder (Mt 5:48) not grind its adherents into the dust? How, for that matter, does a religion that calls all people children of God not lead to complacent mediocrity?

As James KA Smith notes in his wonderful commentary on A Secular Age, meeting that challenge requires a great deal of imagination, lest the choice seem to be between crushing orthodoxy or banal freedom.

Indeed, as Taylor has it, too much of the history of Christianity seems to be a history of this lack of imagination. Many Christian groups have tried to eliminate the gap between quotidian sanctity and heroic virtue. Some do so by denying the goodness of creation, some by advocating for an empty moralism that asks nothing of humans and gives them even less.

But Christianity does not release us from this dilemma between everyday holiness and salvation: it promises a final transformation that is not yet. And so we live in hope toward that transformation. That hope challenges us to stretch ourselves beyond the present even as it consoles us in present difficulties.

Because God loves us as we are. And God also calls us to something more.

How can we live out this tension? As a Jesuit, one of my preferred heuristics for the issue is Taylor’s image of Saint Ignatius of Loyola. For Taylor, Ignatius always lived out the perennial tensions between immanent and transcendent, between everyday and holy, between the renunciation and affirmation of everyday life.

Ignatius did so by living not only in the everyday, but through it: with a sense for what transcends it, to affirm the eternal basis of the temporal. Whatever we do, we “do it all for the glory of God.”

Living this tension is hard work, and in no small part because the challenge of living out tensions is supremely practical. How do we do it? This eschatological tension requires that we learn again how to live together in uncertain, fragile times and no amount of books is going to teach us that. We need practice, and we need friends and teachers to help us along the way.

Thus the importance of moderation for our time. Moderation means finding a mean in all we say and do. We need to eat, but we don’t want to eat too much or too little. We want to be generous, but we don’t want to give away everything. We want to share the truth, but we don’t want to crowd out other truths.

Moderation is not a flashy virtue. But it guides us in so many parts of our life. Moderation is about avoiding extremes that pull us away from our deepest commitments.

In this sense, moderation is among the most concrete virtues. It does not allow us to drift into abstractions, to separate ideals from realities. Those principles are ultimately grounded in a care for persons. It cares about institutions, practices and habits that protect people, particularly the most vulnerable. It therefore neither seeks to raze them to the ground because they are not perfect, nor does it preserve them for the sake of nostalgia.

Christianity does not call us to defend any “-ism”, but rather to proclaim the Reign of God here and now. We might ardently believe that some system of thought or belief helps to advance that Kingdom, but make no mistake: it is a shadow of it, at best.

Moderation does not mean a moderation only about earthly living or transcendent yearning. That would be to try to separate what we know with every fiber of our being to be combined: our present life and the beyond toward which it always points. Moderation cannot mean giving up on the greatest gift of humanity: the final promise that we will all be one, both interiorly and with our fellow humans in God.