I study history for the stories.

Sure there are uses for history: lessons to inform present action and future directions, as a source of identity, as a general practice of trying to come to grips with existential purpose. All of these are good, but it is the stories which impact me the most.

In my recent studies, I’ve encountered the tale of a Jesuit who was sent on a five year excursion, from Northern Indian to China, by land, searching for a (legendary) kingdom of Christians hidden in the mountains and I think his story is fascinating.

Jesuit Brother Bento de Goës was born in the Azores islands off the coast of Portugal in 1562. While not much else is known about his early life, he described himself as having a “dissolute youth” (perhaps not unlike a young Ignatius Loyola).

In his early twenties, he experienced a conversion, and resolved to reform his life and to join the Society of Jesus. He first entered the Jesuits in 1584. At 22 years of age, Goës was older than most applicants to the Jesuits and, for this reason, was informed that he would be a Brother, rather than a priest. Infuriated by this, Goës ran away from the novitiate.

Four years later he returned and was readmitted to become a Jesuit Brother. From this time on, he was known as a model religious: humble service and prudence were his two most praised qualities.

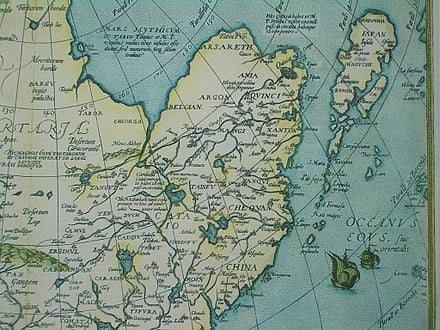

While Goës was quietly ministering at the Jesuit college at Goa, a controversy was brewing among missionaries in Asia and authorities in Rome. Since the explorations of Marco Polo three hundred years earlier, rumors had circulated in Europe of the Kingdom of Cathay—a kingdom of Christains evangelized by the apostles and supposedly located northeast of India and west of China. Though none of them had ever been there, and only a scant few (such as Polo) had heard the rumors of Cathay from merchants traveling along the Silk Road, European mapmakers had nonetheless included Cathay in their maps of Asia for centuries.

In the mid-1590’s, the Jesuit missionary Matteo Ricci, who had been in China for a decade, wrote to Rome that mapmakers had confused Cathay for China, (he argued that there was linguistic and cultural confusion which led to some Muslim merchants believing that the Chinese Buddhists were European Christians).

Eager to come to the truth of the matter, Pope Paul V requested that the Jesuits send someone to travel by land (rather than the usual sea route) from India into China. If they were able to make it to China without coming across a Christian Cathay, then Ricci’s theory would be proved right.

The journey would be a dangerous one. The only ones travelling across these areas were merchants, virtually all of whom were from various Muslim kingdoms and, while being a Christian could cause some difficulties, to be known as a European would be a death sentence. Someone was needed who was both reliable and knowledgeable in the language and customs of the area.

Jesuit superiors chose Brother Goës for the job. They decided that he should disguise himself as an Armenian Christian merchant. So, he grew out his beard, dressed in a robe and turban, and took the name Abdullah Isai (which means “Servant of Jesus”).

Along with an Armenian named Isaac, “Abdullah Isai” left Agra in 1602. During the journey, which would last almost five years, Isaac would be the only one with him who knew Goës’ real name (let alone that he was a Portugese Jesuit).

The route that Goës and Isaac had to take was long and roundabout. Since they were meant to be traveling to China as merchants, they had to follow the customary roads around the mountains and travel in large caravans. This often meant staying in one town for months (even more than a year) while enough merchants arrived to form a large enough group. The size of the group was important for scaring away bandits which were a constant threat.

While most of the merchants he travelled with accepted Goës and Isaac as fellow merchants, not minding that they were Christians, occasionally the citizens or rulers of the kingdoms they passed through were not so accommodating. The most dangerous encounter took place near the end of their journey, in the kingdom of Karashar (today the capital of China’s westernmost province). Upon their arrival in the city, Goës was summoned by the king and threatened with imprisonment if he did not convert to Islam. The king allowed him to leave the palace, but later that night summoned him back. There were some scholars at court who wanted to have an argument with Goës about the tenets of his faith. The king watched intently. Goës’ calm demeanor and simple answers to the scholars’ questions won him over, and the king declared that Christians were to be considered true believers in God.

The king also took a liking to Goës, and wrote him letters to help him pass through the remaining lands on his journey to China. Concerned that others may be hostile to Goës’ faith, the king asked him if he wished to be identified as a Christian in the letters. Goës is said to have responded: “Yes, I most certainly do. I have made the journey this far bearing the name of Christian, and so shall I end it.”

After several more months of travel, Goës and Isaac made it to the Great Wall and officially entered the kingdom of China. Foreign merchants were required to wait in the city of Soceu, not far from the Wall, for imperial permission to conduct business. This process could take over a year. In the meantime, Goës wrote letters to Matteo Ricci and the other Jesuits in China, letting them know of his journey and asking for help in leaving the city.

It took eight months for Ricci to receive one of Goës’ letters, and he immediately dispatched a Chinese Jesuit to go and pick up Goës and Isaac. It took another year for this Jesuit to make it to Soceu and find the travelers. By this time, Goës had fallen severely ill. He lived to meet his fellow Jesuit, the first he had seen in five years. However, he was not strong enough to travel, and died ten days later.

The Chinese Jesuit and Isaac did their best to bury the body of Brother Bento de Goës outside the walls of the city. Neither of them knew the rituals for Christian burial, so they prayed a rosary together over his grave.

It took over six more months to make it back to Beijing. When they returned, Isaac informed Ricci about all of their travels, and gave him what documents of Goës’ he was able to salvage. It is thanks to Isaac and to Matteo Ricci that we know Goës’ story. In his journal, Ricci recounts some of the Brother’s final words. As he spoke about the difficulty of going five years without being able to attend a Mass or go to Confession, Goës stated: “I am dying without this consolation, and yet, so great is the goodness of God, that my conscience does not bother me in the slightest about anything that may have happened in the years that have passed.”

In travelling across central Asia for five years, Goës demonstrated that Matteo Ricci’s theory was correct: there was no lost kingdom of Christians, and the reports about them from travelling merchants were the result of linguistic confusion. More importantly, however, Brother Bento de Goës demonstrated perseverance in both his vowed life and his primary vocation: he ended his journey as a Christian.