I have encountered many well-meaning and Christian people expressing a distrust of fantasy literature. What is particularly striking is that this distrust can come from many different directions and from seemingly opposing “camps” which would be surprised to find themselves in agreement. On one hand, some will criticize fantasy stories as being vehicles of mere escapism which distracts from the pressing needs of the poor and marginalized in our world. On the other, there are those who are suspicious of such stories, particularly those involving magic or supernatural creatures, corrupting young people precisely because those tales suggest reality.

In short, some will criticize fantasy stories for not depicting the “real world,” while others will do so because the world depicted is all too real and they feel it ought to be avoided or rejected.

To the first group I would say that if we stifle our ability to imagine what is not there, then we also run the risk of stifling our ability to imagine what is. To the second, I would say that all of our senses and faculties are given by God for the purpose of drawing closer to Him. While all gifts, imagination included, can be diverted from this purpose, we should remember that God often uses surprising methods of revelation.

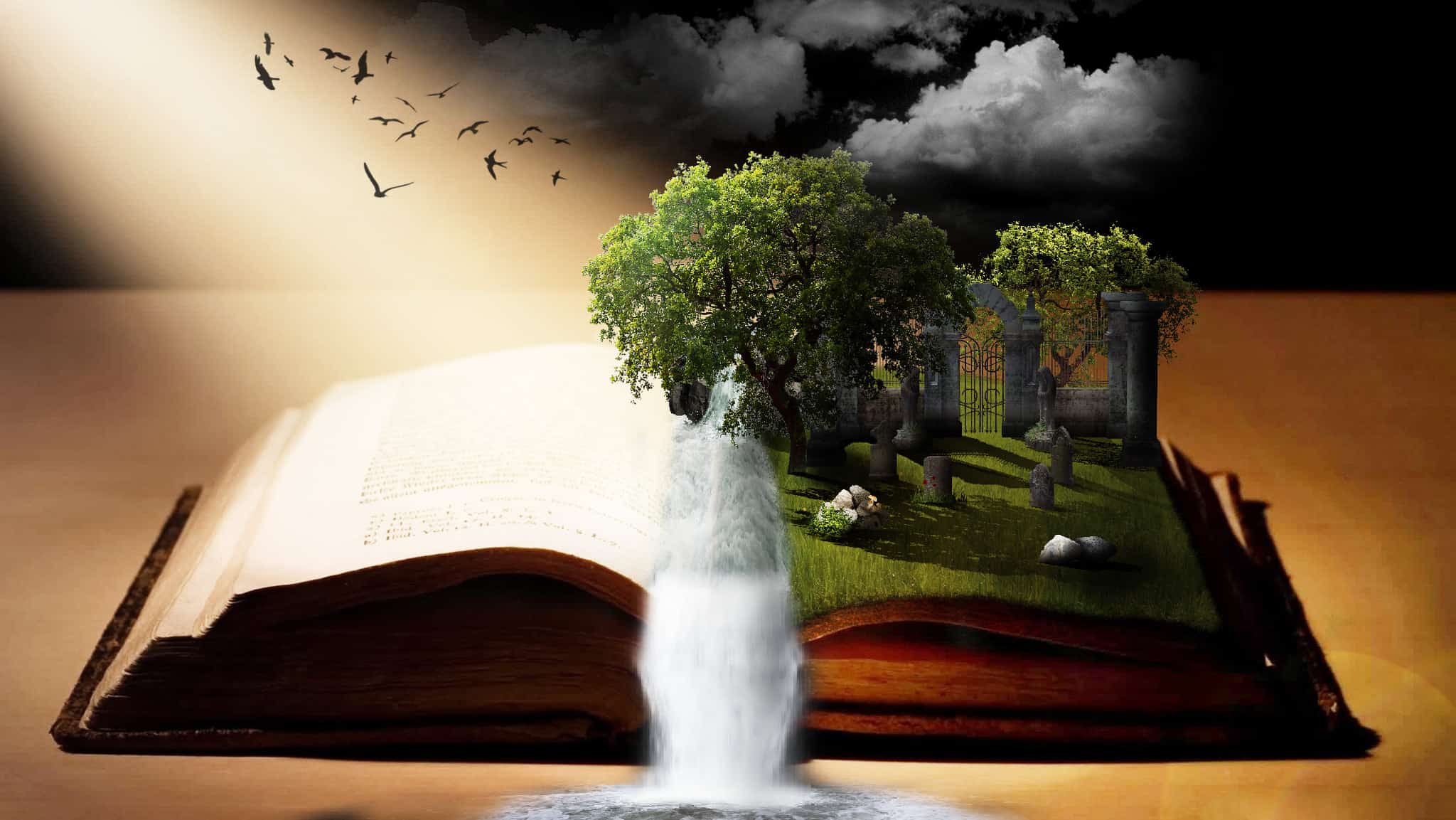

Imaginative literature – which includes the genres of fantasy, science fiction, poetry, fairy tales, gothic horror, and many others – has a long history among Christian writers. When we also consider the arts like painting and sculpture, and techniques of prayer such as Ignatian contemplation, the history of imagination in Christain life becomes broader and deeper.

While escapism itself is not a bad thing from time to time (we all need moments of stepping back and recharging), there is much more to fantasy and imagination, and the literature that fosters them, than that. Here are three points for Christian living and imagining that I have learned from famous writers.

Virtue is a habit; Habits need models.

In his commentary on Dante’s Purgatory, Jesuit activist and author Fr. Dan Berrigan describes the first level, where souls are purged of the sin of pride. They are burdened by carrying heavy boulders on their backs while they view images of various saints and historical figures known for humility. These images, Fr. Berrigan notes, are important: “To play human instead of playing God, we need examples of radiant and sensible conduct.”

All of us need teachers, models, for what it means to live a virtuous life. How can we be courageous? Humble? Loving? Having living role models is vital, of course, but past figures, and even imaginary ones, can inspire the same kinds of lessons. None of us is simply born getting it. Fr. Berrigan continues, “We must imagine the human before we can attain it.”

That need to imagine the human, to be inspired by others and to have models to follow, is not something we age out of. In fact, as we get older and feel the world becoming more and more complicated the need for such guides becomes even more important. While the specifics may have larger consequences as adults, the truth of the virtues remains just as strong then as when we were children. C.S. Lewis understood this when, in his essay “On Stories,” he wrote:

“No book is really worth reading at the age of ten which is not equally (and often far more) worth reading at the age of fifty – except, of course, for books of information. The only imaginative works we ought to grow out of are those which it would have been better not to have read at all.”

Anyone who read The Chronicles of Narnia as a child and has returned to it as an adult will probably understand what Lewis means.

Wonder and humility go hand-in-hand.

The late nineteenth century saw a shift in Western fiction. There was an increase in novels that sought to convey internal struggles and ‘everyday life’ over and against stories which involved the fantastic and supernatural, or the otherwise strange and exotic. The aim of this realistic approach to writing was voiced by Henry James in his “On the Art of Writing Fiction,” when he said that all true art should “compete with life.”

One of James’ contemporaries (and good friends) was Robert Louis Stevenson, whose stories of strange happenings and exotic locations had already made him a well-known figure. In response to James’ essay, Stevenson published one of his own, “A Humble Remonstrance,” in which he wrote that:

“To ‘compete with life,’ whose sun we cannot look upon, whose passions and diseases waste and slay us – to compete with the flavor of wine, the beauty of the dawn, the scorching of fire, the bitterness of death and separation – here is, indeed, a projected escalade of heaven…”

His point is that the beauty and power to be found in life is not replicable in art, including writing. The goal of fiction, for Stevenson, was to excite in readers a passion for life so that they could then go out and live it well. It was about instilling a sense of wonder, and often imaginative and fantastic plots could allow that sense to develop.

This idea was taken further in the next generation by the journalist and essayist G.K. Chesterton, who reflected on his own childhood reading of fairy tales. In chapter four of Orthodoxy, Chesterton recounts how fairy tales taught him that “this world is a wild and strange place which might have been quite different, but which is quite delightful.” The wonder at the world then led to a sense of humility, a recognition that “before this wildness and delight one may well be modest and submit to the queerest limitations of so queer a kindness.”

Wonder leads to humility, and humility leads to gratitude.

In light of the Incarnation, the world is charged with the grandeur of God.

The gratitude which comes from recognizing awe and wonder in the world goes hand-in-hand with a recognition of God’s presence in it all. When the poet Gerard Manley Hopkins wrote that “the world is charged with the grandeur of God,” he was referring to the very energy of existence, of the Source of Life which animates and sustains everything.

This seems like more than enough for which to be grateful, yet within the Christian tradition we see that God’s gift goes deeper still. In the Incarnation, in which this eternal, life-giving Source becomes a human being, not only are all things sustained, they are redeemed. The gift of God’s self, in the person of Christ, raises up all creation to unimaginable heights.

And yet, we are driven to keep imagining.

Whether it is in tales of superheroes, of explorations on new planets or dimensions, of mythical realms with knights and dragons, nothing we can imagine will approach the reality with which God has granted us. What such stories do provide, however, are ways of instilling a sense of wonder and gratitude at what is. And, who knows, “all tales may yet come true,” as J.R.R. Tolkien writes. “And yet, at the last redeemed, they may be as like and unlike the forms we give them as Man, finally redeemed, will be like and unlike the fallen that we know.”

These points are only a few, initial thoughts on the place of imaginative literature in our Christian life. As with the wonder of reality itself, we can always go deeper and always discover that there is more to be amazed by.

To that end, I am happy to announce a semi-regular series here on The Jesuit Post on works of fantasy and imaginative literature. Every other month or so, we will be looking at a particular work and reflecting on what broader lessons can be learned through it.

What written works of fantasy or fiction have been impactful for you? Which would you like to see discussed or reflected upon in this series? Whether it is a classic or a recent publication, feel free to tell us about it in the comments here, or on our Twitter or Facebook pages. Who knows – you might see it in the next entry.

———

Photo by Ryan Hickox