Last Saturday night, Joe Biden gave his first address to the nation as President-elect. He posed the question: “What is the will of the people? What is our mandate?” Then he proceeded to list a series of great battles of our time, including coronavirus, the economy, health care, racial justice, and climate change.

One thing that was not included on his list: immigration.

Throughout the campaign, Biden has advocated for immigration reform while distancing himself from the Obama administration on the issue of immigration, which featured record levels of deportations. And he has decried Trump’s nationalist and xenophobic rhetoric. But he needs to go further. Immigration needs to be a priority near the top of the list.

We cannot wait for that to happen. Change needs to happen in more than just one office in the White House. It needs to happen in hearts and minds across our country. The U.S. Catholic Church, each and every one of us, needs to take an active part in reshaping the conversation around immigration. We need to advocate in a stronger, more unified voice on the need for immediate policy reform. We must take the lead.

*****

Since March, immigrant communities in the United States have been facing an increasingly precarious situation. Immigrant workers in general account for a disproportionate share of coronavirus-response frontline occupations like physicians, home health aides, hospital room cleaners, food producers, and grocery store staff.

Not surprisingly, undocumented migrants in the United States are even more vulnerable, deprived of access to social-safety nets like unemployment insurance or cash assistance from recent relief packages, despite paying billions of dollars per year in taxes. They also continue to face the constant threat of deportation, which has caused many to be afraid of seeking testing or treatment if they exhibit COVID-19 symptoms. Ironically, many undocumented migrants have continued to work because their industry has been classified as “essential,” even as they are treated as disposable, deportable, and undeserving of many public benefits.

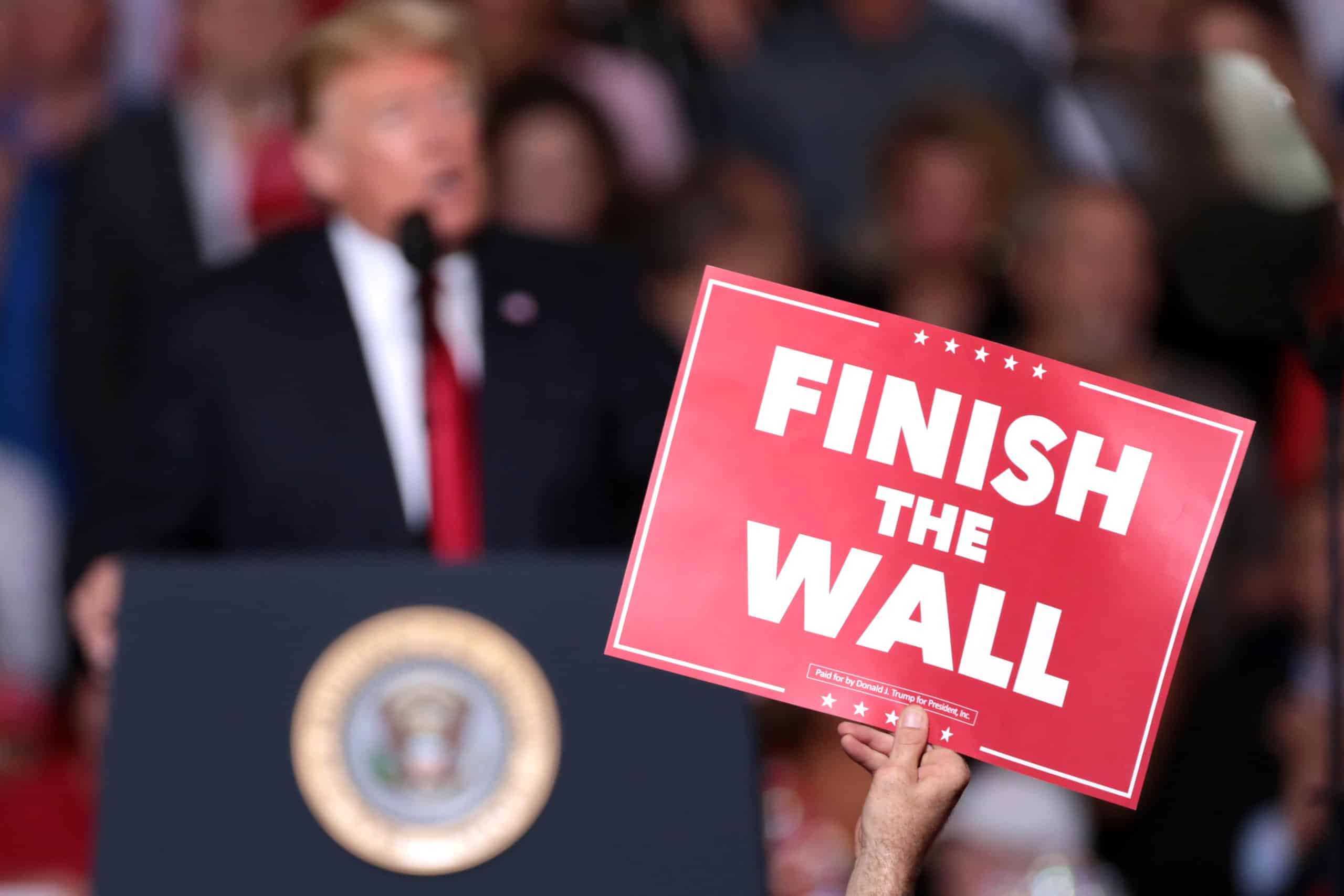

The already precarious situation of migrant communities in the United States has been exacerbated by restrictive policies from the Trump administration. Appealing to health concerns, the Trump administration has expanded travel restrictions, slowed visa processing, and accelerated the return of asylum seekers and undocumented immigrants to their home countries. Immigration detention centers have had alarming cases of outbreaks of coronavirus that are spreading among migrants and staff. At one point in April, President Trump pledged on Twitter to suspend immigration during the pandemic, and then attempted to block new green cards.

All of these policy decisions fell in line with President Trump’s hardline approach to immigration which has been a fundamental component of his platform since the early days of his presidential campaign. Under the guise of health protocols, President Trump has been leveraging the pandemic to advance his anti-immigration agenda.

*****

Catholic Social Teaching is unambiguous in its support of the rights of people to migrate to support themselves and their families, with particular concern for refugees and asylum seekers. The document “Strangers No Longer,” published in 2003 by the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB) along with the Catholic bishop’s conference of Mexico, calls us to embrace the reality of migration, and it outlines extensive proposals for public policy changes.

More recently, Archbishop José H. Gomez of Los Angeles, president of the USCCB, along with other Catholic leaders issued a firm response to Trump’s attempts to restrict immigration: “The President’s action threatens…to fuel polarization and animosity…The global crisis caused by COVID-19 demands unity and the creativity of love, not more division.”

Pope Francis, for his part, has placed the issue of migration at the center of his pontificate. Shortly after his election in 2013, his first papal visit outside of Rome was to the small Mediterranean island of Lampedusa, the epicenter of migration into Europe. The news of migrants dying at sea was “like a painful thorn” in his heart. In his homily there, Francis spoke of a “globalization of indifference,” through which we have become accustomed to the suffering of others and insensitive to their cries. Reflecting on the thousands who have died trying to cross the sea into Europe, Pope Francis poignantly asked, “Has any one of us wept because of this situation? We have forgotten how to weep, how to experience compassion.”

*****

Our Catholic faith begs us for a conversion of hearts on behalf of migrants. Pope Francis offers us the antidote to the globalization of indifference: a “culture of encounter.” This approach has the power to convert hearts and move us to a compassionate response.

He introduced this concept at the very start of his pontificate, preaching on the Vigil of Pentecost in 2013 about the importance of encounter: “It is important to be ready for encounter. For me this word is very important. Encounter with others. Why? Because faith is an encounter with Jesus, and we must do what Jesus does: encounter others.”

As Francis outlined at the Vigil of Pentecost, a culture of encounter is “a culture of friendship, a culture in which we find brothers and sisters, in which we can also speak with those who think differently, as well as those who hold other beliefs…They all have something in common with us: they are images of God, they are children of God.”

Building a culture of encounter is about putting aside differences and seeing commonality: our shared humanity and the dignity of each person as created in the image of God. It’s about breaking down our self-centered introspection and growing indifference to others. It’s about experiencing compassion and remembering how to weep for those who suffer.

Can we build a culture of encounter around migration?

Bringing together groups of U.S. citizens and immigrants can serve as a method of transformation and conversion for all parties. For U.S. citizens, talking with migrants about their experiences and motives for travel can create a real dissonance with the rhetoric of migrants as criminals and threats. Those false narratives and unfounded stereotypes cease to hold up when you get to know the authentic narratives of actual migrants. Similarly, for migrants, the experience of encountering U.S. citizens who want to know their story, or who are offering humanitarian assistance in their time of need, can be transformative. It can help break down their fears about the attitudes of U.S. citizens towards migrants. Thus, encounter becomes beneficial for all parties involved.

What can an experience of encounter look like?

*****

In the summer of 2018, I spent a month on the U.S.-Mexico border in the town of Nogales, Arizona to volunteer at the Kino Border Initiative (KBI), a binational organization coordinated by six Catholic organizations working on both sides of the U.S.-Mexico border in the area of migration.

KBI’s mission is to promote immigration policies that affirm the dignity of the human person and a spirit of bi-national solidarity through direct humanitarian assistance for migrants, social and pastoral education, and engagement in research and advocacy efforts. During my month at KBI, I spent most of my days helping out in the comedor, an aid center on the Mexican side of the border that provides meals for migrants, along with distributing clothing and personal care items and providing orientation for social services and legal assistance. I also spent some time accompanying immersion trips that had come from high schools and colleges around the United States to learn more about migration and encounter the reality of the border. What I learned and experienced during my time there was how KBI is modeling a “culture of encounter” and providing a valuable opportunity for interpersonal solidarity.

The approach to building a “culture of encounter” modeled by KBI can be replicated in a diversity of environments. There are meaningful ways to have authentic encounter within our local communities, even if we live far from the border and cannot travel right now. Immigrant communities are vibrant throughout the United States, including in Catholic parishes and schools.

To build a “culture of encounter,” a local parish or school would be a good place to start. Initiatives that bring students or parishioners face-to-face with immigrant communities, even ones done virtually or at appropriate social distances, can help to foster a spirit of hospitality and correct personal and collective outlooks that might otherwise remain stuck at the level of ideology. KBI’s approach to encounter can help show the way.

*****

We can break down an approach to encounter in three chronological steps: preparation, facilitating encounter, and follow-up. While this would work best for in-person activities, these steps can also guide an approach to virtual events that seek to achieve the same goals.

The first step is preparation.

Encounter between diverse populations can be a complex experience. It is undertaken more fruitfully when there is adequate preparation beforehand. Most fundamentally, this includes planning and logistics. We cannot assume that encounter will happen organically, so we have to be deliberate in planning it. Preparation also goes beyond logistics to include learning about different cultures and contexts, like the history of migration along the U.S.-Mexico border. Preparation should also involve establishing appropriate boundaries for an experience of encounter. Confidentiality, for example, is vitally important if someone is opening up about their migration experience or their legal status.

The second step is actually facilitating encounter.

Facilitating encounter means bringing people together from diverse backgrounds, including U.S. citizens and immigrants, to interact and share. This could be done as a virtual event or with masks and proper distancing. It should provide opportunities to spend time with migrants and hear their stories, in order to humanize the immigration issue and shed light on its complexity. These kinds of conversations are best facilitated by experienced leaders, who are well-trained and knowledgeable and who can help navigate the complexities of the issues. If you don’t have experienced leaders on staff, look for immigration organizations in your area and reach out to them.

To avoid the risk of reinforcing problematic divides, the best approach to the encounter is one where members see themselves as being a single community (such as a united faith community, or even just as part of the broader human family), with relationships set on equal terms. Everyone involved has something to offer and something to gain from the encounter.

The third and final step is follow-up.

Follow-up begins with creating time and space for reflecting on the experience and processing it. Stepping outside of one’s comfort zone can be a jarring experience, so there is great value to reflecting on the experience, including in conversations with others. In addition, follow-up should also include continued engagement and broader advocacy efforts after the encounter is over. Building a “culture of encounter” brings about conversion and that conversion should compel us to action.

All three of these steps (preparation, facilitating encounter, and follow-up) can be adapted for local efforts to build a “culture of encounter.” These steps map out a path to conversion through building a “culture of encounter” that brings together citizens and immigrants alike to recognize our common humanity and to encounter Christ in one another.

*****

With the physical distancing measures in place, the opportunity to authentically build a “culture of encounter” is more difficult. Yet the need for encounter and conversion remains and ever increases. Pope Francis asked: what will our response be “in the aftermath”?

While more will be possible when the pandemic passes, we cannot simply wait until then. Change will take time, years even. We can start the process now, by educating ourselves and others on the issues and by organizing virtual or appropriately-distanced events.

As we near the turning of a new year and the beginning of a new presidency, we need to take the lead in building a “culture of encounter” across the country. The bishops wrote in “Strangers No Longer” that the Church is called to be a sign and instrument, and for too long, the U.S. Catholic Church has not taken enough steps to respond to that call on the issue of immigration. Let’s take the lead now.

President-elect Biden has promised sweeping immigration reform. This is a dramatic about-face from the current administration. We need to hold him to those promises. But change in the White House alone does not mean that anit-immigration sentiments are fading. They still persist.

The approach modeled by the Kino Border Initiative shows us the necessary steps to take: preparation, facilitated encounters, and follow-up. We urgently need to put these steps into action in our local communities. This is the best way to create a hopeful path to positive change beginning with personal conversion through encounter that reshapes attitudes towards immigration. Personal conversion through encounter should then compel us to advocate more widely on behalf of vulnerable migrant populations that are seen and treated as our sisters and brothers.

//

Cover image courtesy of FlickrCC user Gage Skidmore.