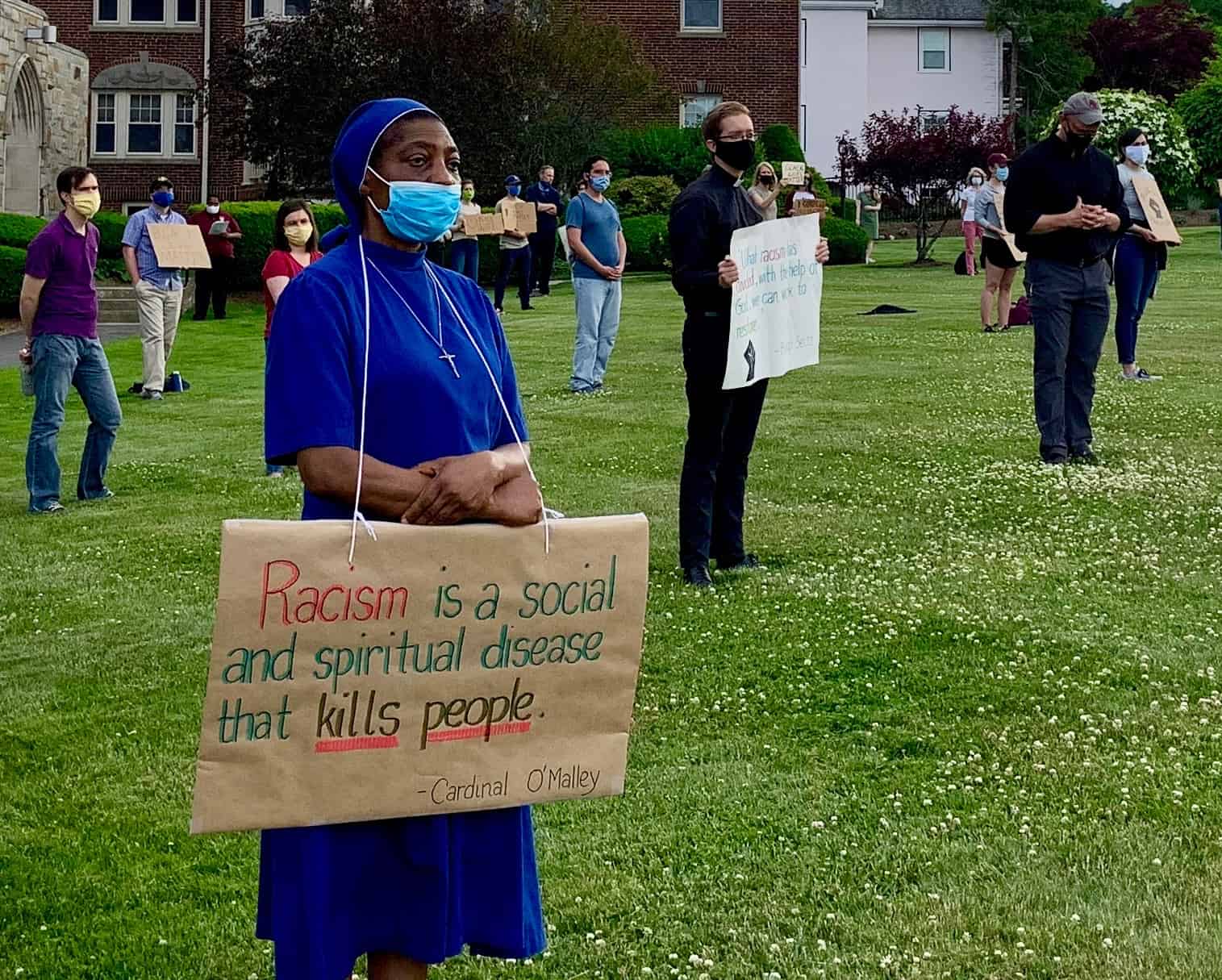

As the movement for racial justice has received greater media attention in the past few months, particularly since the killing of George Floyd by police in Minneapolis, MN, some Catholics may be wondering what to think about the anti-racist movement and how it fits into the Church’s mission. Let’s take a look at a few questions that some Catholics may be asking about the anti-racist movement and see where the Church’s teaching provides answers.

What is racism? And what is the Catholic Church’s stance on it?

When defining racism, it is helpful to consider it in three of its forms, each recognized by the Church: a) racist ideas and theories, b) acts of racial discrimination, and c) systemic racism.

- A racist idea or theory is one that claims that a certain racial group is in some way superior or inferior to other racial groups.

- An act of racial discrimination is one in which a person or group of people are given some type of unjust treatment due to their race.

- Systemic or institutionalized racism refers to the occurrence of institutions and policies that have the purpose or effect of perpetuating or increasing racial inequity.

While a racist idea or theory might explicitly or implicitly lead to an act of racial discrimination, sometimes racist theories and ideas have been created in order to justify pre-existing racist systems, as was the case with the Transatlantic African slave trade.

The Church considers all forms of racism—including racist ideas, acts of racial discrimination, and systematic racism—to be evil. Racism is evil because it violates the fundamental dignity of the human person who is made in the image and likeness of God, and it denies the unity of the human family. Racism has been denounced by numerous popes, including most recently Pope Francis. The U.S. bishops have written that racist actions are gravely and intrinsically evil—meaning that there is no situation in which they are not evil and completely unjustifiable. In 1999, St. John Paul II called on the United States “to put an end to every form of racism” and echoed the U.S. bishops’ belief that racism is “one of the most persistent and destructive evils of the nation.”

What does Catholic teaching have to say about “systemic racism”? How can an institution or a system be racist? Isn’t the problem racist people?

While individual people being racist is indeed part of the problem, racism can also transcend the ideas and actions of individual people when those racist ideas or actions permeate a culture or become policies of institutions. Perhaps the most obvious 20th century examples of explicit systemic racism are South African apartheid and the Jim Crow laws in the U.S. South.

That being said, the Church recognizes that systemic racism also occurs through institutions and policies that do not explicitly refer to race yet are racist due to their effects. The U.S. bishops for example have repeatedly pointed to the ways systemic racism exists in housing, education, employment, and the criminal justice system. When we consider that racism is a grave injustice, the fact that it exists in our country in so many forms means that racism is an enormous problem in need of correction.

What about this idea of “implicit bias”? I don’t understand how I could be doing something racist when I’m not trying to be racist.

Church doctrine provides helpful ways of understanding implicit bias. We talk in Catholic morality about the need to educate our consciences. The catechism states that educating our consciences “is indispensable for human beings who are subjected to negative influences” and that this education “is a lifelong task.” We need to work on developing our consciences, for we might be doing things that we do not even know are wrong and harmful to others. We may have erroneous judgments about our actions due to our ignorance. This does not mean we are evil people, but it does mean we need to learn more in order to change these harmful behaviors.

Since racist actions are sinful, everything in the above paragraph applies to it. A person might be doing racist things without even knowing that what they are doing is racist. They have been so shaped by the negative influences around them that they’ve been malformed to believe racist ideas without even fully realizing they believe them. Those ideas can flow into their words, their decisions, and their votes. Hence, “implicit bias” does not always remain or even begin at the personal level—it has systemic impacts as well. We could be supporting or remaining silent before racial injustice and systemic racism because we have not educated our consciences. Since this education is available to us, this support and silence could amount to sins of omission and complicity.

Therefore, if I hear that an idea, action, or policy is a racist one even though it doesn’t seem racist to me, as a morally responsible Catholic, I should be open to listening to and researching how racism might play a role in that idea, action, or policy. I need to engage in the task of educating my conscience.

What does it mean to be “anti-racist”?

To understand the idea of “anti-racism,” it is helpful to consider what we as Catholics believe about the moral life. If I want to oppose sin and evil in my life, I do not merely “try not to sin.” I try to grow in virtue, and I try to actively oppose evil in society. Think of the problem of lying. If I frequently struggle with lying, simply saying, “Ok, I won’t be a liar anymore” is not enough. I need to regularly examine my conscience to see when I’m telling “little lies” when I did not even realize it. I need to grow in grace and virtue, and I need to practice telling the truth.

But if I really am against lying, I will not just oppose it in myself. I will oppose it throughout society, because I know that lies often cause great harm in people’s lives. I will want to vote a lying politician out of office. If there are lies written into our laws, I will want those laws repealed and replaced with laws based on truth. Additionally, I will demand that the harm that resulted from those lies be acknowledged and repaired as completely as is possible.

It is the same way with anti-racism. Anti-racism is not simply a commitment to saying, “I will not say or do racist things.” It is a combination of continually fighting racism within myself, practicing the actions of racial equity in my life, and fighting against the evil of racism in all of its forms within society—including seeking to bring about racial justice where racial injustice is present.

What would the Church say about reparations for past injustices, such as for slavery? Slavery ended 155 years ago in the United States. Why don’t we just try to treat everyone equally moving forward, and perhaps even place stronger laws in the books for that, instead of punishing people in the present for the sins of the past?

Catholic theology not only supports but requires that injustices be remedied. For example, those who knowingly benefit from theft, even if they did not do the original stealing, “are obliged to make restitution in proportion to their responsibility and to their share of what was stolen.”

In other words, if I steal $1000 from my neighbor and give it to my child, and my child finds out later that the money was stolen, my child must return the money to its proper owner. My child will not need to be punished, such as receiving jail time—I will be—but my child must make restitution. After all, that $1000 could eventually have been passed down, as an inheritance, to my neighbor’s children. And indeed, one of the reasons why the Catholic Church supports the right to private property (checked by the principle of the common good) is so that parents can pass down that property to their children through inheritance.

The fact that it has been 155 years since the end of slavery in the United States makes reparations for these injustices very complicated. The issue is further complicated by the history of government-supported housing segregation and a host of other racial injustices—both past and present. Our country’s brutal history with the Indigenous peoples of this land makes reparations to those communities very complicated, as well. But injustice being complicated does not mean it no longer needs to be rectified. The Church supports affirmative action programs and other creative attempts to find ways to make restitution for the damage done by racism. Again, according to Church teaching, reparation for injustices is not one moral option among many. It is a strict moral obligation.

Even if I agree with the principles of anti-racism and justice, it seems like this will require a massive amount of effort from our country. Is this really worth it when there are so many other important issues?

Indeed, the effort needed has been and will continue to be massive. As the U.S. bishops have written, racism is a “radical evil,” and the fight against it will require “an equally radical transformation, in our own minds and hearts as well as in the structure of our society.” Our country will need to reconsider and reconstruct the way we portray American history. We will need to engage in that “lifelong task” of educating our consciences about the sin of racism. In order to meet the demands of justice, we will have to make significant reallocation of our country’s financial resources. We also will need to seek changes in the policies of our governments at every level, not to mention in so many other social institutions.

The Catholic Church in the United States will need to do some serious self-examination about its own history and present policies, structures, and cultural norms, as well. The Church’s active participation in slavery and segregation was large-scale, and we have not fully addressed the injustices resulting from this participation. We have strong teachings and documents against racism, but as an institution we have failed to live up to them. Surely, fully addressing our history and its continuing effects will be a humbling but necessary process for U.S. Catholics.

We also should remember that by recognizing injustices done to Black people, Indigenous people, and other people of color, this necessarily includes injustices done to Black Catholics, Indigenous Catholics, and other Catholics of color. Pope Benedict XVI wrote that if we want to exercise Christian love toward others, we must first treat them with justice. If we do not treat even our own fellow Catholics justly, then we have not loved them—meaning we have not loved God (cf. 1 John 4:20-21). If the Church in the U.S. as a whole were to continue to ignore the injustices perpetuated upon its non-white members, it would be affirming that our Church’s fundamental teachings of justice do not apply to people who are not white. Such an affirmation and action would only increase in intensity this infected and self-inflicted wound of injustice on the Body of Christ.

All of this work will be difficult, but the basic tenets of morality and justice require it. Discomfort, inconvenience, pain, and sacrifice are not reasons to back down from doing what is right. We follow Jesus, who told us, “If any want to become my followers, let them deny themselves and take up their cross and follow me” (Matthew 16:24). Taking up the cross leads to the resurrection, and that is what makes pain and sacrifice for the sake of truth, goodness, and justice unconditionally worth it.