“Desert sky, dream beneath the desert sky.

The rivers run but soon run dry.

We need new dreams tonight.”

— U2, “In God’s Country,” The Joshua Tree

“Therefore, I will allure her now;

I will lead her into the wilderness

and speak persuasively to her.

Then I will give her the vineyards she had…”

— Hosea 2:16-17

Apparently, my favorite band irks a lot of people.

I can’t deny that. I once heard a U2 fan decry the “political B.S.” that always finds a way into the band’s shows. The problem, author David Dark suggests in his recent article, is that U2 tries to blend “pop hits and social justice.” Their music “offers prophetic critique” and “asks us to look hard at what we are doing.” And prophets irk people.

The band is about to return to the U.S. for a second leg of its Joshua Tree tour, an album that was prophetic upon its release thirty years ago, and which remains prophetic now. It criticizes U.S. military action in foreign lands (“Bullet the Blue Sky”), laments the hopelessness of drug addiction (“Running to Stand Still”), and empathizes with coal miners who have lost their livelihood (“Red Hill Mining Town”).

Sure, the songs apply to different contexts now than they did in 1987. But like a prophetic text from the Bible, they are still relevant so many years later.

I began listening to The Joshua Tree album in May, and went out of my way to see The Joshua Tree tour in June, largely because I was drawn to the prophetic element of the music. I had just taken a course on the Hebrew prophets, who frequently call the people Israel to a period of repentance in the desert. The idea was to return to the stark poverty of the wilderness, where Israel had begrudgingly learned to rely on God — and not merely on themselves — for food, water, and shelter.

I found The Joshua Tree so fascinating because it appears to take the prophets’ advice to heart: Go into the desert, where God will speak. 1 Specifically, the band immersed itself in the desert of Joshua Tree National Park, where they wrote the album. The music that emerged is the band’s effort to share what they heard from God, or what they experienced with God, in the desert.

***

To call U2 “prophetic” may seem simply to glorify the band. But no genuine prophet gets off that easy. In ancient Israel, as now, prophets were rarely popular. 2 They point out problems and tell harsh truths. They challenge us to reevaluate the way we live our lives, individually and as a society. 3 They point out the ways we have gone wrong, and this irks us. It hurts.

But prophets do not irk people just for fun, or out of spite. Rather, their criticism — angry and harsh as it sometimes may be — is an act of love. Hosea famously marries a prostitute to symbolize God’s love for Israel, a people that just can’t seem to give its whole heart to God in return. Hosea, like God, gets angry with his unfaithful companion. But Hosea, like God, cannot help but forgive his spouse and love her anyway. 4

Thus The Joshua Tree, even as it sharply criticizes aspects of American society, is also an act of love. Dark calls it “a love letter to the United States, celebrating its promise while skewering its foreign policy.” Notice that there is no contradiction here. The band can be angry at the United States even as it loves — and perhaps because it loves — the United States. U2 wants the best for us. They want the American Dream to be reality. They want liberty and justice for all. So when they see us falling short of our ideals, naturally, they are disappointed.

Consider “In God’s Country,” which falls in the middle of The Joshua Tree album and, thus, at the heart of each Joshua Tree concert. The band, which is Irish, not American, nonetheless bestows the title of “God’s Country” on the United States. The lyrics proclaim the beauty of America’s “desert skies,” which inspire one to dream. The song also extols Lady Liberty, a symbol of hope to those who dream of coming to America: “She is liberty, and she comes to rescue me!”

But this is no facile ode to America, for the band also notes: “Every day the dreamers die / to see what’s on the other side.”

Even after thirty years, these lyrics seem to speak directly to our immigration crisis. So many migrants, desperate to find liberty in the U.S. — from war, poverty, gang violence, or other problems — quite literally “die to see what’s on the other side” of the U.S. border. Sure, Lady Liberty holds out a torch that guides “the tired, the poor, the huddled masses” to safe harbor in America. 5 But perhaps we have made it so difficult to legally enter the country that the American Dream rings hollow. Rather than find liberty in the U.S., many meet their death. The dream, all too often, becomes a nightmare. And so, as U2 sings, “we need new dreams tonight.”

***

Lest we write off The Joshua Tree as a mere liberal rallying cry, the album also laments the plight of coal miners. It is no secret that our current president has promised to bring back coal and to send immigrants back home. While it is easy to view these two groups, immigrants and coal miners, as opposed, The Joshua Tree challenges us to see that justice is lacking for both.

U2 invites us to empathize with coal miners — or with anyone who has lost job and livelihood — in “Red Hill Mining Town.” Bono takes on the voice of an unemployed coal miner, for whom Labor Day is no longer a cause for celebration. On the contrary, Bono mourns the days when coal miners had work: “Our Labor Day has come and gone.”

Not unlike the refugees from “In God’s Country,” Bono’s coal miner tries to cling to the American Dream: “I’m hanging on! / You’re all that’s left to hold on to. / I’m still waiting!” 6 Even though he is a citizen, even though his family might have lived and worked in the U.S. for decades, the coal miner finds himself waiting — still — for the comfort, security, and prosperity that America purportedly promises. You can hear the pain in the miner’s voice as Bono moans, “We see love slowly stripped away; / Our love has seen its better days.” The song offers no happy resolution. It ends with surrender, or perhaps even despair: “The lights go down on Red Hill Town.” Without coal mines and the power they provide, the miner’s town — and a whole way of life — is extinguished.

***

If we are to live up to our ideals and fulfill the American Dream, U2 challenges us, then we all have some growing to do. “All are welcome here, left or right,” Bono said in Chicago. But all are challenged too. Those who oppose immigration reform need to empathize with the migrants who would “die to see the other side” of a U.S. border wall. At the same time, those who support immigrants and refugees, myself included, must learn to empathize with poor American workers who feel, after years of labor in some of the country’s hardest jobs, they’re “still waiting” for the American Dream to kick in.

This, in essence, is what makes U2 prophetic. They love America, but they also know we can be better. They see injustice and point it out, on the left or on the right. That can be irksome. But if we are never irked, if we tune out the voices that call us to change, we will never grow. We will simply stagnate, staying stuck where we are, dreaming the same old dream.

-//-

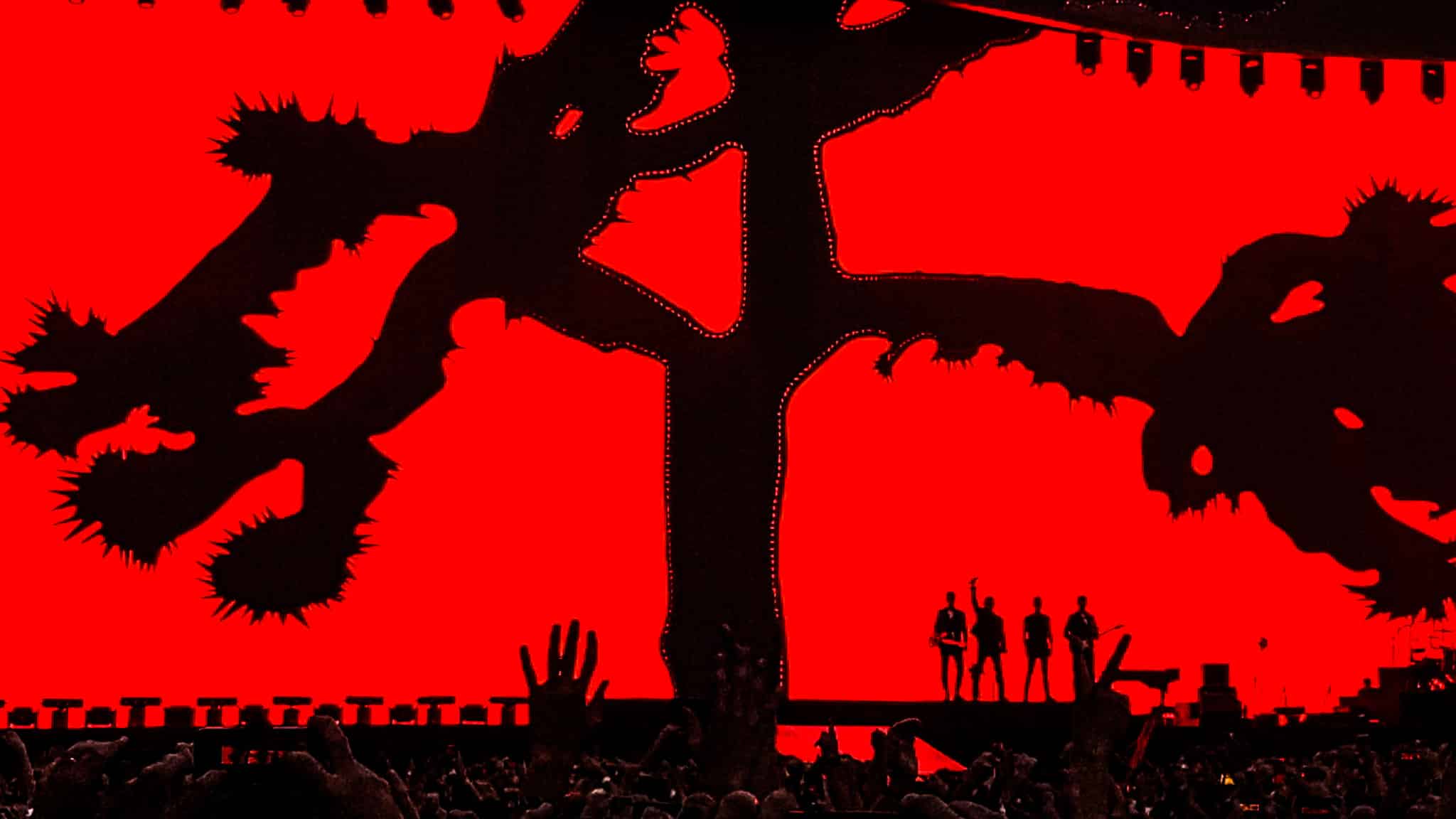

The cover photo is featured courtesy of Gisueppe Milo of the Flickr Creative Commons and is a photo of the current U2 Joshua Tree Tour 2017.

- See Hosea 2:16-17, above ↩

- Just look at Jeremiah, who at one point wishes he’d never been born (Jer. 20:14-18) ↩

- In Dark’s words, they “ask us to look hard at what we are doing.” ↩

- Nowhere is this tension between anger and mercy more evident than in Hosea 11 ↩

- Though our present administration has recently tried to suggest that even these words don’t really express the ideals of our nation. ↩

- Interestingly, Dark hears these lyrics as “the cry of an asylum seeker.” ↩