Pope Francis was widely expected to reform the Vatican. Has he?

Yes and no. The change has been more a matter of evolution than revolution, and has only been partial in many areas. Indeed, even the pope seems unhappy with the pace of change. But given his frequent predictions of a short papacy, Francis seems intent on laying the foundations of a reform that will continue for years after him.

Curial reform

When people speak of reform in the Church, they often mean a reform of the Vatican curia. Indeed, Pope Francis has reserved some of the harshest words of his pontificate for his Christmas addresses to the curia. As John Allen notes:

Let’s begin by acknowledging two truths about the Catholic Church.

The first is that everyone loves complaining about the Vatican. Whether you’re liberal or conservative, from the First World or the Third, no matter what kind of Catholic you are, griping about the slowness, arrogance and dysfunction of the bureaucracy in Rome is a favorite indoor sport.

The second truth about Catholicism is that if we didn’t have the Roman Curia, meaning the central administrative bureaucracy of the Vatican, we’d have to invent it.

So how does one reform a set of institutions that are at once deeply problematic and indispensable?

As is so often the case, “reform” has taken the shape of reshuffling and restructuring personnel and institutions. But do the new structures work any more effectively? This is particularly the question with the new Secretariat for the Economy and the two new massive dicasteries for Laity, Family, and Life and Promoting Integral Human Development.1

The new Secretariat for Communications seems bound to be an improvement, although that is partially because policy had to change with personnel: the indefatigable Federico Lombardi, SJ is no longer around to wear five hats at once.

The Secretariat of State remains unwieldy and probably too powerful. People often use the word “bureaucratic” to describe it, but in fact that is what it is not. Where “bureaucracy” refers to a system that organizes personnel and resources in a way to maximize leverage over policy implementation and oversight, the Vatican curia has tended to be a network of overlapping, often redundant offices that fight for turf.

Of great concern, also is the Italian domination of the Vatican curia, something that has been talked about since at least 1970. Many commentators saw the pope’s appointment of the Australian Cardinal George Pell, for instance, as a move to destabilize the Italian power cliques within the Vatican. But non-Italians, strangers to the language, history and culture of the Curia and Rome, have historically not fared well in the Curia, as Pell’s own difficulties suggest.

Allen also raises an unexpected but vital question: when will this reform end?

Yet there’s a real and present danger to a never-ending cycle of reform, one that Pope Francis and his “C9” council of cardinal advisers will probably have to confront head-on in the not-too-distant future, which is demoralization and paralysis within a workforce that doesn’t know when the next shock to the system may arrive.

Curial reform has been a mixed bag, with much yet to be done and many effects only to be known in the future. But we must also wonder what “normalcy” will look like in the Curia when the dust settles.

Financial reform

Here we see some of the brightest hopes for improvement. The Vatican has gained a reputation as central Italy’s premier money-laundering destination, with terrible scandals dragging the Vatican’s name into the mud. Pope Benedict XVI took steps to reverse that situation, a process that has Francis has continued with great energy.

That said, as John Allen notes, the financial reforms have not unrolled as expected.2 Recent reforms, for instance, have shifted financial power from the new Secretariat for the Economy back to the Secretariat for State. While the Secretariat for the Economy was supposed to scale back the powers of the secretary of state, “it’s now clear that the Secretariat of State is the king of the mountain once again in terms of setting policy, while the Secretariat for the Economy has become essentially a resource center and compliance office.”

Whatever has led Pope Francis to reform his reform, it is clear that his original plans for the Curia have been re-shaped in the face of implacable realities.

Ecclesial reform

More subtle have been the pope’s reforms in the relationship between Rome and the local churches. Most dramatically, he has sought to work more closely with the College of Cardinals by regularly convening the “C9”, a kind of executive committee of the Cardinals. He has also sought advice from a disparate array of voices in his choosing of cardinals.

Amoris Laetitia has also turned out to be an important aspect of Francis’ reform. While much of the controversy has concerned the status of moral teachings at stake in the document, no less a part of the dispute has concerned who is authorized to interpret and apply those moral teachings, and the bounds of interpretative possibilities.

Indeed, synodality and collegiality are buzzwords in this pontificate. But the controversy over Amoris Laetitia suggests that thematic reflection on those concepts is necessary.

***

Those expecting cataclysmic reforms to the Vatican forgot two things: bureaucracies change slowly, and Italian bureaucracies slowest of all. If the president of the United States has little control over his bureaucracy, the pope can perhaps be forgiven for the same.

But perhaps we have also forgotten the very words of the Pope:

This discernment takes time. For example, many think that changes and reforms can take place in a short time. I believe that we always need time to lay the foundations for real, effective change. And this is the time of discernment. Sometimes discernment instead urges us to do precisely what you had at first thought you would do later. And that is what has happened to me in recent months. Discernment is always done in the presence of the Lord, looking at the signs, listening to the things that happen, the feeling of the people, especially the poor.

But I am always wary of decisions made hastily. I am always wary of the first decision, that is, the first thing that comes to my mind if I have to make a decision. This is usually the wrong thing. I have to wait and assess, looking deep into myself, taking the necessary time. The wisdom of discernment redeems the necessary ambiguity of life…

Reform must be slow and intentional, the Pope reminds us. But if there is any truth to the trope that St. John Paul II was primarily outward-looking toward the world and Benedict XVI in-ward looking toward the Church, then there is something admirable if challenging about Pope Francis’ desire to be both outward-focused and concerned about the internal life of the Church.

*****

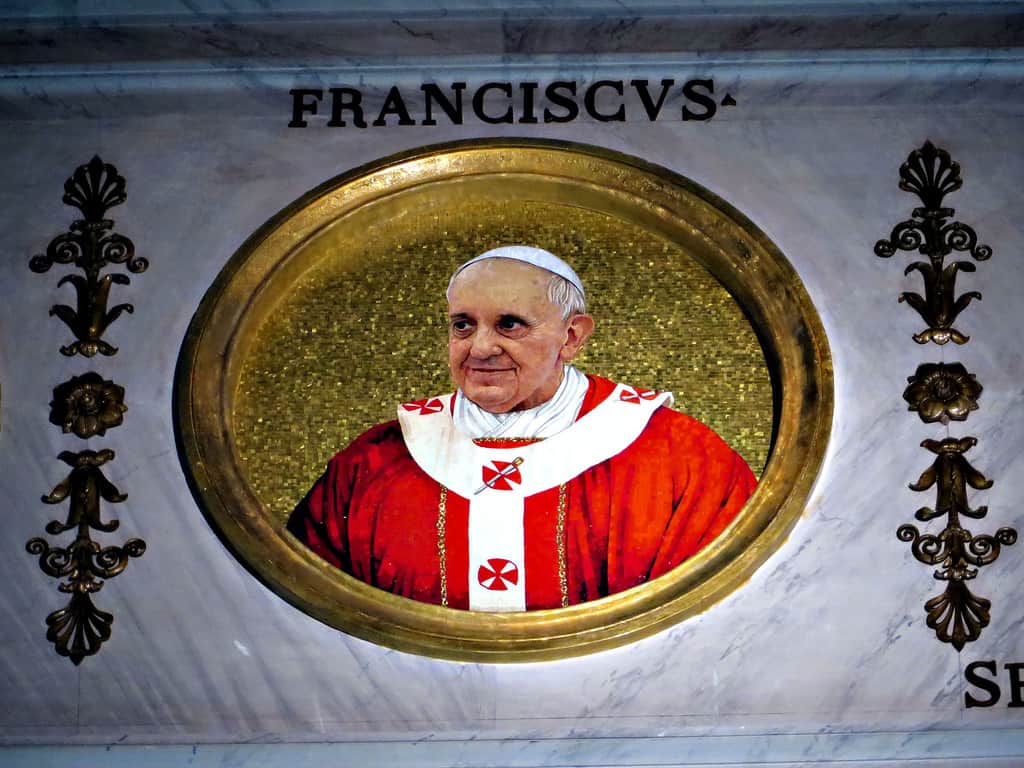

Image courtesy FlickCC user Fowler Tours.

- Most of the documents establishing these bodies can be found here. ↩

- If this article is beginning to look like a summary of John Allen articles, that’s because he is one of the best Vatican watchers in the U.S. Few journalists cover the Vatican as well and as thoroughly as he does. ↩