As even the most casual observer can tell you, political and social life in America is, well, dysfunctional. This is hardly a new state of affairs, because — I would argue — our collective dysfunction is rooted in the hidden dysfunction of our personal relationships. If the old statement that art mirrors reality is true — and I think it is — then it should come as little surprise when novels point out these overlapping layers of dysfunction. And perhaps it is even less surprising that they don’t have much good to say about the way we live now.

Six years after publication, I revisited Jonathan Franzen’s Freedom (2010), one example of that fiction that points out the unseemly underside of this American life. But Franzen also shows why our age should write and read such novels: even if we live in anti-heroic times, there is still hope for us.

* * *

Like so many stories, Freedom revolves around an unhappy marriage. And like so many unhappy marriages, both spouses were unhappy long before they married each other. Walter and Patty could not be more dissimilar: he is of modest Midwestern stock, and she is the child of Westchester wealth and privilege. What they have in common is their rebellion against their families. Patty surprises and disturbs her intellectual family by excelling at basketball, but then decides she wants to become a housewife. Walter becomes a progressive activist dedicated to bird conservation and human population growth.

But neither rebellion works out the way they planned. Walter goes to law school, becoming part of the very system he wants to bring down. While possessed of strong principles, he is actually driven by childish jealousy of a college friend.

Patty re-invents herself as the good wife, but somehow always finds ways to disturb her family’s peace. She dotes on her undeserving son to the neglect of her talented daughter, and manages to re-ignite an old flame. But the flame, Walter’s aforementioned college friend, happens to be the only person who loves Walter as much as she does. The revelation of the adultery leads to their breakup, but the marriage has been over for years. The irony, if not the tragedy, runs deep.

* * *

As you will have guessed, a major theme of the book is compromised principles. The book is littered with lies, hypocrisy and self-deception, and Franzen is not afraid to search out such wrongdoing at the highest levels. The book, which came out in 2010, is set largely during the contentious years of the first decade of the new millennium. This allows Franzen to connect the family drama to national events that are no less sad, desperate, and (seemingly) without solution.

What Franzen points to in 2010 is even clearer to us in 2016: the United States lives in the grip of tremendous fear. We do not have the child-like faith in the future that characterized our national ethos for so much of our history. This fear chokes hope, and this loss of hope strangles freedom. For while we may still be free in many respects, in lacking hope we are confused about what we need to be free from and free for.

Patty and Walter are drowning in this confusion. The title Freedom is particularly apt: the characters are all trying to break free from the people and things they think are holding them back. But they don’t ask themselves what they should be free for. And when they look beyond their individual lives to the wider culture, they don’t find much hope for happiness there, either.

This cultural dysfunction justifies Patty and Walter’s rebellion: a part of them sees that America has to change. And so, in classic American form, they aim to reinvent themselves. But their self-invention is not supported by any part of the society in which they live, and thus their lonesome project is a failure. And that is the greatest irony of the book: the principles that Patty and Walter constantly compromise are of their own making.

Indeed, Franzen makes it clear that Patty and Walter aren’t any worse than their parents or grandparents. But whatever supported those past generations in their idiosyncrasies and insulated them from their failures is gone. Patty and Walter won’t get the life their parents had.

I could not help but think of solidarity while reading this book, because solidarity is precisely what is missing. The people in Freedom never really connect with each other, and rarely know true friendship or love. They’re always hiding behind anger and sorrow — unknowingly imprisoned by such emotions — and they can never say or do quite what they want to, always grasping for something deeper than what they can express. With all of the disappointment and frustration in their lives, they can’t help but see others as enemies from whom they must hide all their failures, and upon whom they must heap all their blame.

Yes, there is a deep disconnect in their culture, and it operates at the highest levels. But it also enters into the most basic human relationships, and even in the individual relationship.

* * *

Franzen is depicting one part of a vast phenomenon. It might be too much to expect him to offer any solutions to these complex problems. But I think he does show a way forward. Despite the ridiculous situation Walter and Patty get themselves in, they [spoiler alert!] are able to save their marriage in the end.

This moment comes at the end of the book. Patty has returned to Walter after a six-year separation, and makes herself sick waiting outside Walter’s house in the cold Minnesota air. He finally breaks down and lets her in, and warms her in his arms. This leads to the first genuinely intimate moment of the book:

And so he stopped looking at her eyes and started looking into them, returning their look before it was too late…

With that look, and in that embrace, they gain the freedom to see each other, and to see themselves, for the first time.

“It’s me,” she said. “Just me.”

“I know,” he said, and kissed her.

For once they don’t see each other as mirror images of their broken dreams and hollowed-out hopes. Rather, they see each other as human. Perhaps in a time when it can be hard to be human, it is the task of good art to remind us that human is what we are.

–//–

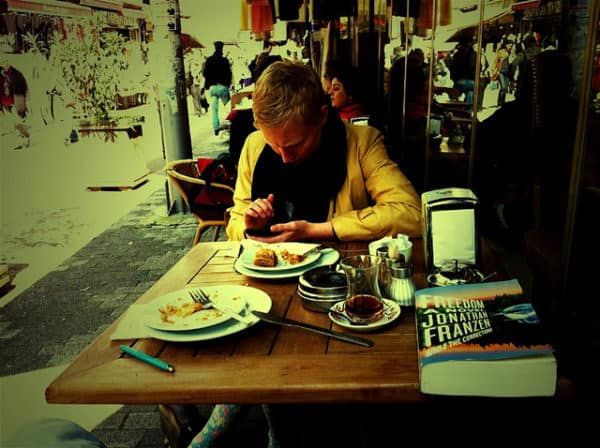

“Åkte över till Kadıköy. Där läste man vidare på sin episka roman.” by Flickr user storuman, is available here.