Joe Assadourian, standing at a sturdy 6’2’’ and sporting a thick Jersey accent, greeted my Jesuit friend and I as the lights dimmed and the curtain was drawn: “Step into the Bullpen,” he rumbled.

Who is this man? I wondered. Where is he taking us?

The Bullpen, I learned, had nothing to do with Mariano Rivera getting the last three outs in the ninth. Instead, it was Assadourian’s take on what it is like to be “on the inside.” Inside a jail, that is.

Assadourian was the entire show. For 65 minutes, in the main we were treated to bouts of laughter, as he imitated the 18 characters you meet in jail: the Italian mobster, the guy who’s constantly stoned, the Latino guy who speaks English so fast you don’t know it’s English, the clueless judge; the transgender prostitute.

One of the characters was Assadourian himself. He meets these characters in the bullpen, a large holding cell for those arrested and awaiting trial. Arrested on assault charges, Assadourian is faced with a big decision: should he take the plea (5 years in jail) or risk going to trial? The characters mentioned above help him by conducting a “mock trial” to see how the evidence might hold up in court.

“Speak English, hombre,” the judge cried to bouts of laughter. Everything seemed so ridiculous. Until I realized – this is real.

It was horrifying to connect the dots. What we were watching was not a “mock trial” but a mockery of a trial. It was the true story of Assadourian’s trial and sentencing. He wrote it while he was doing time. The clueless judge suddenly ceased being funny and became a source of frustration. His constant admonition for the characters to speak English moved from the comical to the offensive. It was a show of sharp turns and emotional jerks.

Immediately after it ended, we were invited to an onstage conversation about our nation’s incarceration problem with the Central Park Five.

“Who’s that?” I asked my Jesuit friend. He shrugged his shoulders.

I rarely go to post-production conversations or interviews. See the show, be entertained, go home. That’s my philosophy. Still, I wanted to know what happened to Assadourian. What was it like for him to do the time? Did he see things differently now as a free man?

So I stayed. Connected to Assadourian after spending the past hour with him, I was willing to give him- and the Central Park Five- a bit of my time.

The story of the Central Park Five is well documented. Literally. As in a Ken Burns documentary[1].

In 1989, five boys, all between the ages of 14 and 16, were charged with the assault and rape of a 28 year old white female jogger in Central Park. All the boys were African American or Latino.

Three of the “Five” joined Assadourian, the show’s director, and a state senator on stage as the conversation began. As I listened it was Kevin Richardson, Yusef Salaam, and Raymond Santana, the members of the Five, who kept capturing my attention.

“It was hilarious,” Salaam said about the play.

“And way too accurate,” responded Richardson.

Navigating both the juvenile justice and adult prison systems, these boys spent the remainder of their teenage years and their twenties being treated as if they were something less than human. They were rapists in prison, and they were treated as such.

“In jail, rapists are the worst of the worst. Even the other prisoners look down on you,” Santana said.

They spoke about how everyone treated them as if they were guilty even before their conviction. Media reports came down hard on the boys. Pete Hamill’s April 23, 1989 piece for the New York Post is emblematic. He wrote:

[The Central Park Five] were coming downtown from a world of crack, welfare, guns, knives, indifference and ignorance. They were coming from a land with no fathers. . . . They were coming from the anarchic province of the poor. And driven by a collective fury, brimming with the rippling energies of youth, their minds teeming with the violent images of the streets and the movies, they had only one goal: to smash, hurt, rob, stomp, rape. The enemies were rich. The enemies were white.

So much is contained in Mr. Hamill’s statement. Fear, hatred, anger, ignorance, racism. He is constructing a narrative to stir up anger and frustration in the reader. The success of this narrative depends upon his characterization of the Five as rapists, thieves, criminals. No attention is paid to them as not-yet-convicted human beings. Even 25 years later they are hard words to read.

Initially I wanted to distance myself from words like Mr. Hamill’s, but I wonder if they don’t speak to some of my own prejudices. What narratives do I construct to justify my privileges and lifestyle? Do I make internal assumptions about people of different races or religious beliefs? I would never risk expressing those assumptions, of course. But a glance inside shows me that they exist.

Clearly, Hamill’s words were representative of how many people felt about the Central Park Five at the time. The emotional narrative of five African-American and Latinos attacking an innocent young woman in New York’s hallowed Central Park swept people up. They forgot to ask, “What about these boys? What about their needs and rights?” They forgot to ask, “Did they actually do it?”

They didn’t. The Central Park Five were convicted without DNA evidence and with inconsistent testimonies from witnesses for the prosecution. In 2002, they were exonerated of the crime when police received a confession (and DNA evidence) from the man who actually did.

***

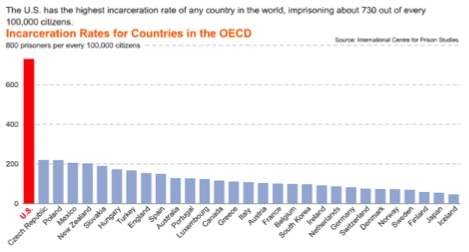

We have an incarceration problem in our country. For most of us, this is hardly news. Much ink has been spilled addressing this, ranging from the accessible to the academic. A quick Google image search of “Incarceration Rates” yields a slew of charts like this:

Or this:

Somehow, the fact that charts like this are google-able don’t make them any less shocking.

The Central Park Five is a story about failure – the failure of our legal system to discover the truth, the failure of so many to give these boys a honest chance, the failure to live out our American hallmark value “innocent until proven guilty,” the failure of a system that is quick to judge and to convict and slow to listen and understand.

There was a moment while watching The Bullpen I stopped seeing Assadourian as a character and started seeing him as a human being. His trial became a serious thing, his comical questions demanded real answers. There was a moment when I thought:

How can you not weigh the evidence? Isn’t there a greater burden of proof for the prosecution? Isn’t there a “reasonable doubt”? Why should it matter if the defendant (or his lawyer) speaks English well or not?

These sorts of questions may be familiar to anyone who has tuned into the excellent podcast “Serial.” We want to believe in our justice system. We want to believe that jurors are educated and impartial, judges patient and understanding. We want to believe that the media takes its objectivity seriously.

It’s hard when the facts don’t let us support this narrative.

Nevertheless, interspersed amid this shared systemic and personal failure, minor gestures become majorly important.

During a question and answer segment of our conversation, I asked Santana, Salaam, and Richardson what sustained them throughout those thirteen years, knowing they were innocent. They gave answers you might expect. Visits from family. Letters from friends. Each other.

Then, after a pause, Salaam started telling a story. “One time,” he said, “I came back to my cell to find a pack of Entenmman’s Cookies and a Tropicana juice box on my pillow. I thought they were trying to poison me, so I didn’t have them. Then I found out it was from our prison guard. I will never forget her. I guess what sustains you is really anything that makes you feel human.

— — // — —

[1] Available on Netflix!!!!