“Despite its beauty, this is a place of brokenness.” So said the guide sheet handed to tourists (like me) upon entering Ely Cathedral – a massive, spectacular Anglican church that rises out of the English countryside some 80 miles north of London.

Mine was an accidental pilgrimage – the happy result of having arrived extremely early for another appointment. And so I found myself wandering slowly through this imposing Norman edifice, and lingering especially in the Lady Chapel. This was the space that the guide sheet described as beautiful and broken, as many of the intricate statues in the chapel were defaced (literally – their visages chiseled away) during the Reformation. Rather than trying to remedy the excesses of bygone religious fervor, a recent restoration left the faceless statues untouched.

My trusty guide invited me to pause here, in order to “pray about the brokenness, grief or loss” that marks my life and the lives of those I love.

Unbidden, a kind of slideshow started flickering across the screen of my mind. In one frame, a friend who several years earlier found herself shattered by the sudden, unexpected disintegration of a happy relationship with wedding bells tolling in the distance. In another, images of friends who struggled or struggle with cancer or other illnesses, vulnerable and often scared. In another, scenes from my own life, especially the wounds of the past that seem slow (or impossible) to heal. The places that just don’t make sense, and maybe can’t. The kind of memories that the mind either avoids altogether or seems utterly incapable of avoiding.

And I stood there, beauty and brokenness coexisting in the same space, at the same time.

***

When I teach Introduction to Theology at Loyola University Maryland, my class reads the “Autobiography” of Ignatius Loyola, and one of the subsequent final paper options is for the students to pen a spiritual autobiography. Ideally, choosing this paper allows students to reflect on places where their own narratives have intersected questions of theological or religious meaning.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, stories of “brokenness, grief or loss” fill these pages, but the theological questions that emerge from personal experience are perhaps even more important than the narrative itself. Often enough, they sound something like: “Why would God do X, Y, or Z?” I find this question completely understandable. Faced with a mystery, especially the mystery of suffering, who among us hasn’t asked a question precisely like this one?

Often enough, the resolution of these questions comes down to the ubiquitous statement that “everything happens for a reason.”

Let me be clear: I hate this saying. I hate it for complicated reasons that would take a much longer essay to explain. But I hate it mostly because it can mean several wildly different things, and it’s rarely clear which one the speaker (or here, the writer) intends.

On one level, yes, everything happens for a reason. When I got my first and only (so far) black eye, there was a reason (sister, argument, snowshovel…long story). This pithy phrase can also indicate the view that, in ways we cannot imagine, there are good things that can come out of bad situations (breakup, sad music, enter soul mate). Again, no problem.

But often it seems something else looms behind this statement: that the reason something awful happens is the inscrutable will of God. In other words, suffering is somehow visited upon us by God in order to teach us a lesson – a lesson that will (ultimately) be to our benefit. Admittedly, this is a recurrent idea in the history of theology. But it is also has the potential to be enormously problematic: if ‘everything’ really means everything, what reason can we possibly give for, say, genocide? What reason for infants with Leukemia? And if everything happens for a reason – God’s reason, no less – when does God cease to be worthy our worship and become a morally deficient monster?

The implication of these words for brokenness is simple enough, even if the theological issues they raise are not. In the end, pain, suffering, and vulnerability are realities to be overcome and endured, not mysteries to be welcomed or inhabited. They are tolerated only until they teach us the needed lesson. Only until wholeness can resume, in other words.

***

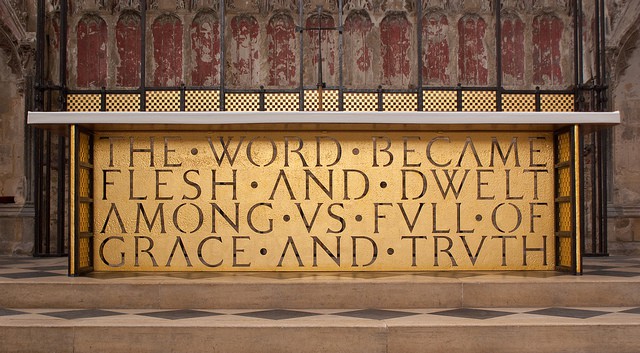

Perhaps by now we are shockproof against the idea of the Incarnation. Perhaps especially at this time of the year, as Pandora and 24-hour Christmas radio stations confidently broadcast, as though it were an ordinary thing, “Veiled in flesh the Godhead see! Hail the incarnate Deity!” or “Word of the Father, now in Flesh appearing.”

Whatever else we might say about them, early Christians lacked our armor against these ideas. So did the surrounding intellectual and religious culture. God taking flesh? Haha. Go home, Christians, you’re drunk. Even some of those who thought Jesus to be divine were scandalized by the idea of a true flesh-and-blood Incarnation. This was mostly because physical matter was seen to be either unworthy of God, evil by nature, or both. This was especially true of ‘corrupt’ human flesh, characterized by its unruly passions, its flickering mind. Our bones and blood were widely seen as impure in their generation and birth, marked as they are by vulnerability, suffering, and death. God could no more “inhabit” flesh than a human could breathe underwater.

When religious types speak of the “suffering and death” of Jesus, conversation inevitably turns from Advent and Christmas to Lent and Easter. The focus shifts from Bethlehem to Jerusalem, which is understandable.

But can we linger a little longer around that manger, and see what we see? A vulnerable child. A savior who must quickly be saved himself, smuggled to a foreign land to avoid Herod’s jealous wrath. A teen who, according at least to pious historical speculation, would have mourned the death of the only father who would (could?) wrestle with him or teach him to fish. An adult who wept for a dead friend. A friend who was no stranger to the sting of betrayal and rejection by treasured companions.

Maybe this is why Jesus’ preferred demographic was the broken-down and the down-and-out. Maybe “The Lord is close to the brokenhearted and saves those who are crushed in spirit” not just because he’s really nice and helpful, but because that’s the only way he knew how to be a human being.

Maybe if we linger a little longer around that manger, we might glimpse the peace this Prince actually brings: the peace of broken things.

***

I’d be lying if I said I love this about Jesus. Most days I can only tolerate it, and some days I resent it. Very infrequently do I welcome it. Truth is, I am much more comfortable with a God who expects me to have my shit together, despite my lingering sense that such a thing will never come to pass. Or at least a God who expects me to fake it. Or at least a God who would prefer it if I were a little less obviously broken, thanks.

An Emmanuel who is less “God with us” and more “God tolerating us.”

A god made in my image and likeness – not the other way around.

***

The good news is that God seems decidedly unconcerned with our sense of propriety. The Emmanuel we have is better than the counterfeits we might conjure and even worship.

The German theologian Johannes Baptist Metz, in his slender but mighty book Poverty of Spirit, says that in the Incarnation Jesus “came to us where we really are – with all our broken dreams and lost hopes, with the meaning of existence slipping through our fingers.”1 He came not to wave some magic wand, so that everything might make sense, so that no one would get sick and die, so that relationships would never wither and decay. The Gospel is many things, but it is a poor roadmap for a light and carefree existence.

“He came and stood with us,” Metz says, “struggling with his whole heart to have us say ‘yes’ to our innate poverty.”2 The One we welcome in this Christmas season stands with us in this place of beauty and brokenness, which is our world. Which is each of our lives.

O magnum mysterium: the One we embrace at Christmas has already embraced us. Embraced especially what we so often resist and fight about us. He stands in those places, perhaps where we’d least like to look for him, waiting.

— — — — —