Andrew Romano over at the Daily Beast really liked HBO’s True Detective; his final review calls the show ‘close to perfect.’ I liked the series as well, but I’m not willing to go quite that far in my praise. I’m with Emily Nussbaum at The New Yorker on the ways in which this show isn’t perfect (i.e. its philosophic musings are muddled and the female characters are, problematically, both thinly written and scantily clad – a popular HBO combo1 [NSFW]). While the show may not be perfect, it remains an intriguing romp for the religious viewer.

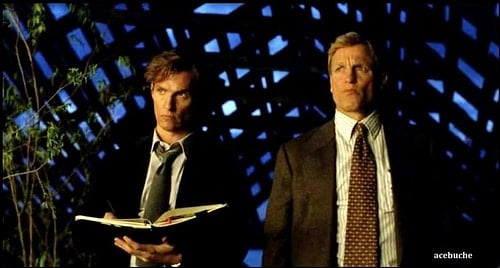

True Detective is both a murder mystery and a character study. Most episodes split their time between a murder investigation full of cultish religious symbology (implicating a potential serial killer) and an interrogation of the two primary investigators which occurs years later (implicating, in mysterious ways, the two of them). The title of the show is revealing as the show’s gaze rests not only on the case but on those trying to solve it. As viewers we follow the investigation as we also question the trustworthiness of the investigators. Detective Rust Cohle, played by Matthew McConaghy, spins a vague and dark philosophy of human depravity while Detective Martin Hart, played by Woody Harrelson, lives a life torn between presumed moral virtue and obvious lapses in perfection – lapses which are painfully preoccupied with sexual purity (for his women) and indiscretion (for himself). Let’s just say, there are no white-hatted heros here.

In an earlier review, Romano wonders if the show is anti-Christian and concludes that it’s ultimately about the power of storytelling. This much I agree with. What I can’t accept is the narrow way in which he understands religious narratives to be merely escapist fantasies. Romano creates two categories – stories told to escape reality (religion) and stories which reveal it (investigation). Surely there are those who seek to avoid reality, but the vast majority of Christians I know are religious not to escape the truth but rather because their faith sheds light on it.

Being religious helps people to understand reality in greater depth, particularly the experiences of suffering about which this show is uniquely concerned. The religious folks I know don’t seek to avoid reality as much as they hope to fully appreciate it. Truly religious narratives aren’t psychopathic delusions or escapist coping mechanisms. In the face of real suffering, religiously faithful people are often less concerned with deliverance than they are with redemption.

As a religious viewer (in every sense) I found the way in which an investigative story can also be a salvific narrative is what made watching this particular show interesting. Similar to the BBC’s Top of the Lake (which I also reviewed here) the writers of True Detective are explicitly concerned not only with the criminal investigation per se as a path toward solving a case (a path which seeks deliverance from mystery) but also with the ways in which the principal characters experience (or fail to experience) redemption and healing in the midst of their own suffering.

Consider the final moments of True Detective [spoilers ahead]. Rust Cohle, the nihilistic investigator, is confronted by his own awareness of how much he loves and misses the daughter he lost tragically many years before. His partner, Detective Martin Hart, attempting to console him in a moment of profound grief, asks him to recall a story, a story Rust himself told him years ago. It’s a savvy pastoral move – inviting the grieving to become a storyteller – and it’s a striking moment not of an investigative narrative as much as a religious one. It’s a healing story and, as Rust notes, it’s the oldest one there is – it’s a story about light and dark.

The surprise ending here (for us as much as for Rust) is an acknowledgement of love in despair, light in darkness. This narrative is at the heart of religious belief and it’s a kind of darkness called ignorance to suggest that religious storytelling is necessarily opposed to investigation and the search for truth. Romano’s view of religious narrative (and he’s certainly not alone in this view) ignores the truth of religious experience. He presumes the religious perspective to be one which avoids reality instead of one interested in probing it’s sacred and harrowing depths.

Certainly there are delusional stories that arise from psychosis and trauma, but true religion seeks truth. In the end, for the nihilist grieving the sad loss of his own child, this story is about facing reality more than it is about escaping it; it’s about redemption more than deliverance. It is only in experiencing grief that his own story of light (a story he actively represses throughout the investigation) becomes credible. It becomes credible because it is rooted in the reality of his experience, in all of its pain and sorrow, its grief and longing.

In the end, being a true detective, like being religious, is not only about finding the bad guy, it’s also about experiencing your experiences and keeping an eye on the light in the midst of darkness. What made this show worth watching (and even sacred) is how the investigation was about the detectives – their crimes, their sufferings, and their wrenching attempts to make a way in the messiness of their own lives. After much investigation – external and internal, broadly (if vaguely) cosmological and profoundly personal – the conclusion of this show is brutally honest and religiously hopeful. It’s full of grace because it’s a love story.

This is not delusional. This is sincere testimony. Detective Hart says in the final shot of the season as he gazes up at the night sky, “The dark has a lot more territory.” His grieving partner, Rust Cohle, the hitherto nihilist, quickly responds with a final line that sounds a lot like what Genesis tells us happened, well, in the beginning. Rust speaks with the authority of lived experience – after profound personal investigation and having finally faced his reality instead of escaping it – as he says, “Once there was only dark. If you ask me, the light’s winning.”

******

Cover Image Credit: Flickr user ¡¡¡!!! / Flickr Creative Commons, https://flic.kr/p/jDPPms

- Editor’s note: This link connects to a popular video that satirizes our culture’s willingness to justify pornographic content because it’s on HBO. ↩