On Wednesday, November 7, 2012, the lead article in The New York Times crowed: “Barack Hussein Obama was re-elected president of the United States on Tuesday, overcoming powerful economic headwinds, a lock-step resistance to his agenda by Republicans in Congress and an unprecedented torrent of advertising as a divided nation voted to give him more time.”

More time is also what we have for considering how our notions of race and racism have evolved over the last two presidential elections.

***

Several years ago, while working on a master’s degree in American Studies, I took a seminar on the works of William Edward Burghardt Du Bois. The seminar was taught by a professor who was a self-proclaimed “race man.”

I scoffed. Really? A “race man”? This is the 21st century, I thought. Find yourself another research interest. I should add here that while I consider myself a black man, my life does not fit neatly into our racial categories. Born in Arkansas, raised in Hawaii and Southern California, race was something that I ran with tennis shoes, not a category to which I belonged. I grew up in an educated, solidly middle-class family, with a Malaysian stepmother and an Indian grandmother. Now I happily concede that I am black, in fact Very Black. But until this seminar, I had scrupulously avoided identifying myself with this dangerous racial category. Now that I’m a “race man” too, I’m still haunted by the jarring, prescient question Du Bois put to blacks in this country a century ago: “What does it mean to be a problem?”

The problem can be sketched with the kind of numbers that remind us that America has a permanent underclass: 27.4% of blacks live under the poverty line, 46% of black children live in poverty, which has disastrous effects on health and educational attainment1 According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, one in three black men can expect to go to prison in their lifetime. I could go on. In spite of giddy declarations of the end of race, the obvious effects of slavery, segregation, and Jim Crow are painfully, obviously, with us. It is no wonder, with such a historical burden on our conscience, that many of us desire to invest in simple solutions to eradicate this evil.

Du Bois argued that the problem of race would forever torment post-emancipation America, and named it the distinctive American “tragedy.” But for all of his prescient insight into the “problem” of race, even the way Du Bois talked about race was not always helpful.

Du Bois lived in a time when race was largely attributed to biology. The consensus among researchers today is that human races are sociocultural constructs. But to say that race, biologically speaking, is dead, does not mean that it is not alive and well in America. Whether considered taboo or passe, the fact remains that word “race” is still used to justify both inferiority and superiority. It’s true that this outdated, and largely unhelpful, mode of thinking has largely been assigned to history’s rubbish bin,2 it’s also true that we Americans still need to rid ourselves of the misconception that race is a genetic trait.3 What does it matter what science tells us, or what scholars say about race as a sociocultural concept when popular discourse still holds onto a biological construct of race? Or, to put it provocatively, what does it matter that race as biology does not exist, while racism does?

In his book The Uncompleted Argument: Du Bois and the Illusion of Race, Anthony Appiah (himself of hyphenated, Ghanaian-British-American identity) observes that Du Bois acquiesced to a dubious biological concept of race. And Appiah, in his strenuous attempt to undo the negative effects of such phony biologism, offers a critique of race that can seem, at first glance, just as dubious. He claims that it doesn’t exist at all:

The truth is that there are no races: there is nothing in the world we can ask race to do for us. As we have seen, even the biologist’s notion has only limited uses, and the notion that Du Bois required, and that underlies the more hateful racisms of the modern era, refers to nothing in the world at all.

But Appiah is using hyperbole – and perhaps not helpfully. Appiah is not saying that race is not perceived, nor that racism doesn’t exist. What he means is that race has no definable content or essence. It’s a fiction whose terms change depending on the minority, ethnicity, era, and history of prejudice against a group. For example, in medieval and early modern Europe, Jews were considered the “dark-skinned” race. But when Jews emigrated to America, that term of “darkness” was already in place for African-Americans; hence, American anti-Semitism uses different terms than anti-Semitism derived from European sources.

So while “race” in Appiah’s analysis does not actually exist, forms of racism do, which is why Appiah coined the phrase “intrinsic racism” to describe our modern problem. Intrinsic racism views each race as having a different moral status, brooks no contradiction and is immune to evidence that would overturn its assumptions. Appiah contends that the problem of racism in America is that we are in thrall to intrinsic racism, that we all too often hold onto racist attitudes regardless of the evidence presented.

But, it might be asked, we’re a country that just elected a black president to a second term – what does intrinsic racism say in light of a second inauguration of President Obama?

***

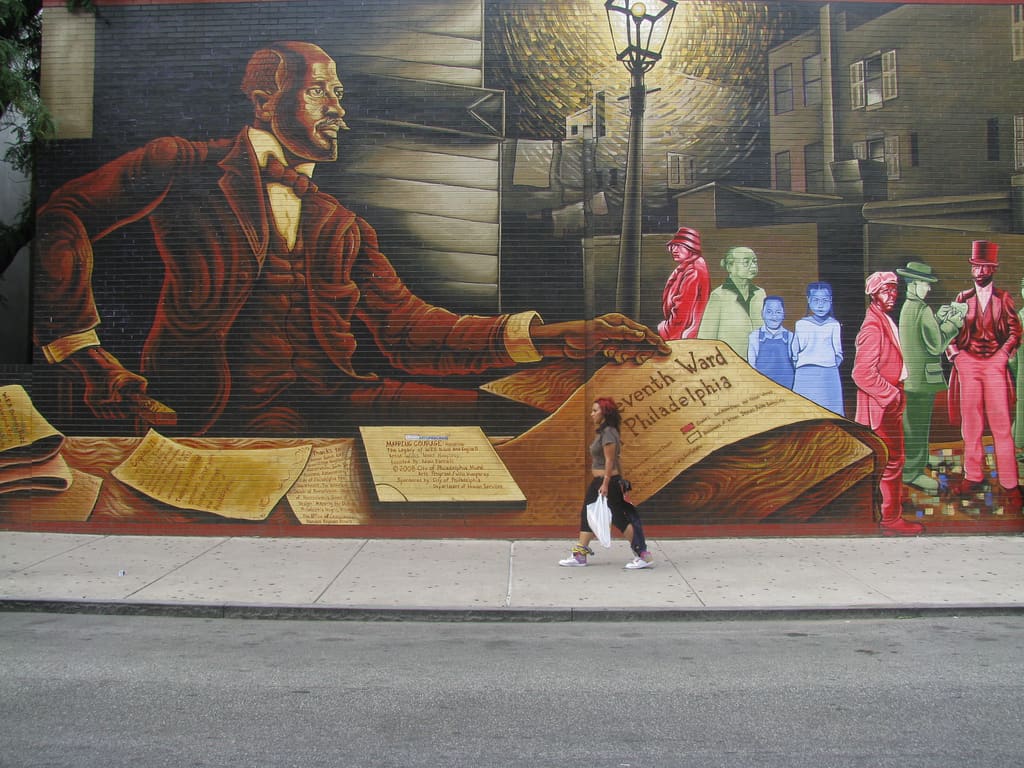

DuBois Philly Mural by Lauren(elle)n at Flickr

Twelve years prior to President Obama’s candidacy, Dinesh D’Souza, a man who seems to always enflame progressive angst, published his flimsy, pseudo-scholarly book, The End of Racism.4 According to D’Souza’s logic, if racism has a historical beginning – say, the end of slavery – then it must have a historical end. In 1995, D’Souza supposed that sufficient evidence was then available to show that we had reached the endpoint of racism. If lightweights such as D’Souza thought it could be done in 1995, there are still plenty of folks who think it’s only a matter of (short) time before we can answer the question: how can we know when we have reached the end of racism?

Enter President Barack Hussein Obama, circa 2007.

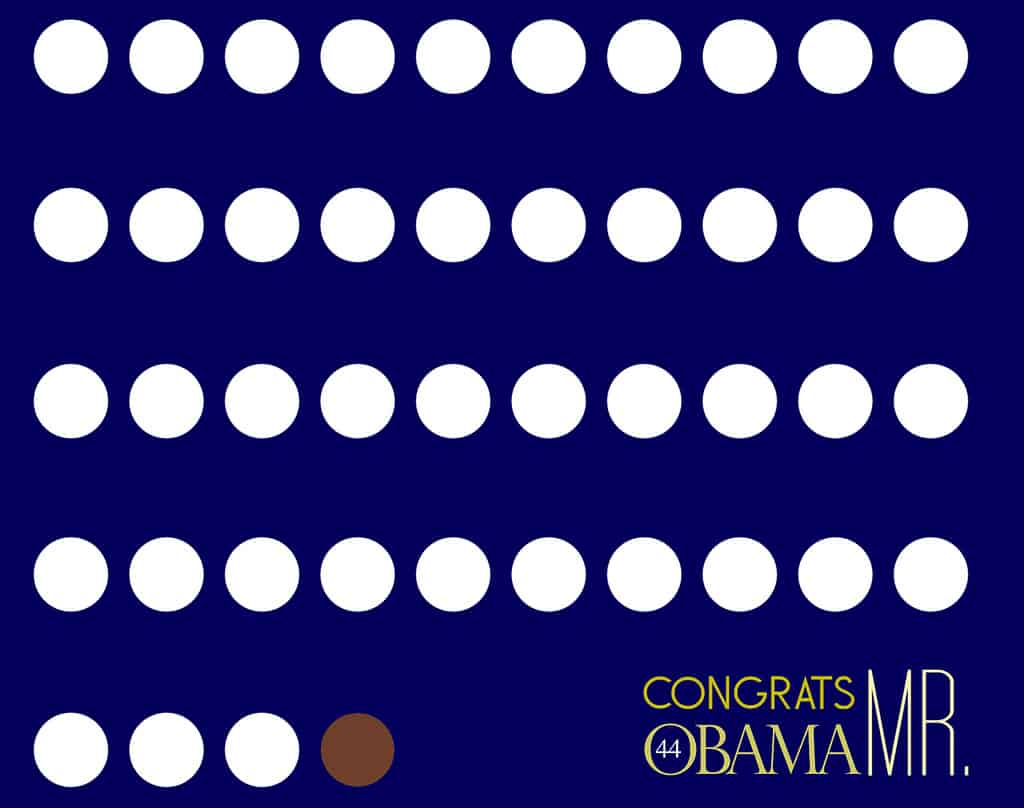

What more evidence could we want? According to Donald R. Kinder and Allison Dale-Riddle, author’s of The End of Race?: Obama, 2008, and Racial Politics in America, more. The engine of Kindler and Dale-Riddle’s book is a question: how did race affect the election that gave America its first black president? They argue that, if not for the effects of racism, Barack Obama would have won the election in a landslide. Their reasoning? While the identification of black voters with Obama helped to increase black turnout, “what race gives, race can take away,” and they also found that racial resentment and stereotyping among white voters powerfully predicted votes against Obama.5 More specifically, Kinder and Dale-Riddle estimate that Obama’s racial identity cost him approximately ten percentage points off his final victory.6

We can draw two conclusions from this analysis. First, Obama created a passionate sociocultural buy-in with black, Hispanic, and Asian voters that propelled him to victory. Second, Obama’s background cost him a certain percentage of white voters who privately held reservations about voting for a black candidate. Does this sound like the end of race? I do not think so. Rather than end, in the 2008 presidential election race was more powerfully operative than ever.

***

When Senator Obama became President Obama, the country collectively sighed. At least our media did. The New York Times captured the gist of many front pages when it announced “Obama Elected President as Racial Barrier Falls.”7 On the one hand, we can read this headline as pertaining solely to the fact that the country just elected its first black president. On the other hand, recall the television coverage and the articles in newspapers and magazines in the wake of the 2007 election. Much of the narrative went further than Obama becoming the first black president. His victory was supposedly a victory that transcended race and somehow defeated racism.8 Both liberals and conservatives put Obama’s victory in a pine box labelled: “The End of Racism.” In subsequent days racism would be waked and eulogized. Its funeral would happen on inauguration day. And on inauguration day of ’08 all parties seemed to be in agreement: racism was a thing of the past. The discussion of race was to be passé. In other words, stop talking about race.

***

But’s it’s not dead. And there’s no use telling us to stop talking about what needs to be talked about. Four years ago, as this nation patted itself on its collective back for electing Obama the details of the voting patterns from that election went largely ignored. But now it’s 2012, and a second inauguration has just come and gone. Surely it’s better now.

That’s not what the numbers say. The 2012 presidential election results skewed even more heavily toward the proverbial rainbow coalition: Romney won 59% of the white vote. Obama won 93% of the black vote, 71% of the Hispanic vote, and 73% of the Asian vote. Racism hasn’t died, there just seems to be a disconnect between our media narrative of “Transcendent Victory” and the deeply ingrained reality that Appiah has pointed out to us: intrinsic racism is alive and well.

Several weeks prior to Obama’s reelection in 2012, the Associated Press published a survey on race (you can download the pdf here, or read a summary here). This survey, completed in 2011, finds that a slight majority of Americans express prejudice toward blacks. Even more, explicit tests showed that 79% of Republicans and 32% of Democrats held some form of racial prejudice while implicit tests showed that 55% of Democrats and 64% of Republicans held anti-black sentiments. And this after four years of a black president in the White House. It comes down to this: a biracial, Harvard-educated, former law professor at the University of Chicago has not been able to sway the considerable portion of the electorate who hold anti-black attitudes and sentiments is astonishing. Intrinsic racism is alive and well.9

We wanted race to be dead, to eulogize and bury it, but intrinsic racism is too deep to be rooted out simply by electing a black man. Voting alone cannot absolve us of our complicity in racial bias. I think, now that a second inauguration has come and gone, that the biggest problem we face vis-à-vis race is that we do not want to admit that the election of a black man was not the game changer many of us thought it would be.

***

Shortly after World War II, a reporter asked Richard Wright for his views about the “Negro problem” in America. Wright replied, “There isn’t any Negro problem; there is only a white problem.” I disagree. The problem is race itself. The persitent existence of implicit racism in America is a white and a black problem. It is a systemic problem, persisting in us and around us. It is a problem that we must discuss. And it is a problem that begs for precision and personal reflection. It is not easy to talk about a problem when we are part of that problem.

So I return to Du Bois’ prescient question and ask again: what does it mean to be a problem? It means that this nation has not yet made peace with its past. It means that the Blacks, Hispanics, Asians, and minority of white voters who bet heavily that an Obama election would move this nation towards freedom from its racial history still have work to do. It means that, whatever good may have come of these past four years, the realization that our past is present is disappointing – a disappointment made all the more bitter because of that unreachable ideal licensed by the very racial constructs for which we are all responsible.

— — — — —

- US Census Bureau. Current Population Survey. People in Families by Family Structure, Age, and Sex, Iterated by Income-to-Poverty Ratio and Race: 2007 ↩

- Which is not to say that there is no genetic variation between races, as evidenced in the distribution of sickle cell disease and the prevalence of certain genetic diseases in Ashkenazy Jews to name a few. However, there is no scientific basis to draw social, cultural, or moral conclusions from these tiny variances. ↩

- This is the message of Race?: Debunking a Scientific Myth, by Ian Tattersall and Rob DeSalle and Race and the Genetic Revolution: Science, Myth, and Culture, edited by Sheldon Krimsky and Kathleen Sloan. ↩

- A book one critic zinged as a “700-page doorstop by a one-time AEI scholar that no one cites today.” ↩

- Kinder and Dale-Riddle use data on attitudes toward race from the quadrennial National Election Studies surveys. ↩

- In the end, McCain won the white vote 55-43 percent while Obama won blacks 95-4 percent, Hispanics 67-31 percent, and Asians 62-35 percent. See Cost, Jay (November 20, 2008), “HorseRaceBlog—Electoral Polarization Continues Under Obama and Kuhn, David Paul (November 5, 2008), “Exit polls: How Obama won.” While Kinder and Dale-Riddle’s analysis has been criticized as overzealous by some, the raw numbers support their main conclusions. Non-white voters invested heavily in that election. White voters were the least likely group to vote for Obama. ↩

- Obama’s election was seen as a culmination of the work of Martin Luther King Jr, Rosa Parks, W.E.B. DU Bois, and many others who worked towards racial equality. ↩

- One of the more striking claims of the Transcendent Victory Narrative came from Thomas Friedman of The New York Times, when he wrote, “The Civil War is over. Let reconstruction begin.” Many people connected Obama’s victory within a larger victory harkening back to this country’s history. The New Yorker’s editor David Remnick wrote an essay a few weeks after the election entitled: “The Joshua Generation—Race and the Campaign of Barack Obama.” Remnick detailed the campaign’s use of the theme of race, especially the hope that the ills of race could be erased with Obama’s candidacy. In other words, the Transcendent Victory Narrative was shared by the Obama campaign. ↩

- The survey also finds that 52% of non-Hispanic whites express anti-Hispanic attitudes and confirms the research done by Donald R. Kinder and Allison Dale-Riddle that Obama stands at an estimated net loss of 2% due to anti-black attitudes. Explicit survey questions asked respondents whether they agreed or disagreed with a series of statements about black and Hispanic people. For example, the survey takers were asked how well certain labels such as “friendly,” “hardworking,” “violent,” and “lazy” described blacks, whites, and Hispanics. Implicit surveys relied on photos of blacks, whites, and Hispanics displayed on a screen and gauged people’s initial reactions. ↩