Ellis Island as seen from the Statue of Liberty

Perhaps the most terrifying part of doing legal work is how banal it can seem. This thought struck me as I sat in a nondescript chair at a nondescript desk in a nondescript cubicle behind an unremarkable office façade and listened to a heart wrenching story.

Across from me was a young woman from the African country of Guinea. In soft, slightly accented English, she told me her story.1 This is what I remember: as a young teenager she had been given, in a cultural marriage that may or may not have been recognized by civil authorities, to a man far older than her. Physical, sexual, and emotional abuse ensued. Pregnancies as well. In her soft voice she told of being forced to flee when he tired of her, and became almost murderous. She spoke of being abandoned by her family, entering the United States and overstaying her visa. She told of fighting to get a decent job. She paid her taxes, she said, and found a man who loved and cherished her. She had put her life together. Now, she wondered aloud to the stranger across the nondescript desk, “is there anything I can do to regularize my situation?”

I knew the answer before she asked, but found myself almost unable to tell her. The frustration of wanting to offer sympathy, help, ran up against the majesty of the law, a majesty which holds no room for emotion. It was – it is – frustrating. Before I gave a final answer I asked a few follow-up questions, hoping I had missed something. Or maybe just to put off the awful moment. Because, you see, I’ve found the worst thing I can say as a lawyer – both for me and the person I’m helping – is “there is nothing I can do.”

The most difficult part of those six words is having to say them more than once, and this lovely African woman is just one of many who has heard them. Good and bad, criminal and refugee, immigrants come. They come seeking welcome and too often are left with little besides the hope someday, someone will change the system.

Perhaps, in the wake of November’s national elections,2 our country will find a new readiness in both parties to admit that our immigration system is broken and to act to reform it. Because that’s the reality. Our system has become so burdened and jumbled that it’s unable to engage immigrants as persons. They become just cogs in a machine.

I’ve been doing some thinking about the immigration scene today, especially about how divisive and contentious it is. And I think there are two problems at the heart of our immigration dilemma that we can find some common ground on: a major backlog of legitimate cases, and the language we use to talk about immigration. Let’s the take the longer discussion – the case backlog – first.

***

In today’s immigration system family-based immigrants are forced to wait for anywhere from a few years to decades to have their legal requests granted. That’s right, decades. For the privilege of asking to live in this country.

Green Card

This is how it works: visas are issued by the State Department. Those who want to immigrate to the United States (“intending immigrants”) must be in a family relationship to a current citizen or legal permanent resident (i.e., a holder of the infamous “green card”). When an “intending immigrant” applies, the Department will determine if she falls in one of the eligible family relationships and, if she does, issue her a “priority date” that saves her a place in line, until a visa number becomes available. Now, because there are strict limits on the number of visas that can be issued each year, the Department actually can’t issue enough visas to cover all applicants.3 This line has gotten pretty long.

How long? Say you qualify and you’re applying today, how long will your request take? Best case scenario: about two and a half years. Worst case scenario: over twenty three years. Yes, you read that right, twenty three.4 If you’re from the Philippines and your sibling is a U.S. citizen, and you applied filed in March of 1989, your application is currently being considered.

Yep, you could have filed your application after watching the premiere “Disney’s Chip and Dale Rescue Rangers” on March 4, 1989 and still be waiting. If you did, you’ve been waiting longer than “The Simpsons” have been on the air (and yes, that reference may have mostly been an excuse to link to the Simpson’s premier).5 To be fair, certain classes – particularly opposite-sex spouses and minor children of U.S. citizens – generally have immediately-available visas outside this system. They do not have to wait for a visa number to become available, but they do have to complete the rest of the process.

But even with such exceptions we have to remember that being granted a priority date is just the first step. All that does is give permission to apply for a visa. You may not get one, and if you do then you must come to the border and be inspected and admitted by the Department of Homeland Security. And then you have to wait at least five years before you can begin the process to become naturalized as a U.S. citizen.

So yeah, it’s bad on the applicant side, but the system doesn’t look any better on the receiving side either. The immigration courts6 (where we seek to justify the removal of non-citizens) are just as backlogged. According to the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse run by Syracuse University, as of September 30, 2012, there were 325,044 cases pending in immigration courts. Each of these will wait, on average, 570 days before coming to trial. In Los Angeles (which to the surprise of nobody hears a ton of immigration cases) the wait is 745 days; over two years of waiting in legal limbo. And the vast majority of these (let’s be exact: 25,667 of the 325,044 cases, or 8%) are not criminal, terrorist, or national security related.7 And what about the judges who are hearing these cases? According to the Office of the Chief Immigration Judge, there are 260 immigration judges in the country, each of whom have an average of over 1200 cases pending. Put all these numbers together and what we have is no not a recipe for successful, thorough, humane justice. It is an assembly-line.

I could continue piling up numbers, but I think you can see the point, which is this: our immigration system, before we even begin talking about the gritty details of what kind of immigrant we ought to admit, is broken.

***

What does it mean to conclude from all this data that our immigration system is nothing more than a broken assembly line? Partly, it means that we Americans have agreed to view immigration like UPS views package delivery: as a logistics problem. Instead of seeing human beings sitting before us, we can start to see them as products, little bits of fleshy machinery to be processed and shipped out to their proper places. This is even true of the kind of language we use: referring to immigrants and immigration as “legal” or “illegal” blinds as much as it clarifies.

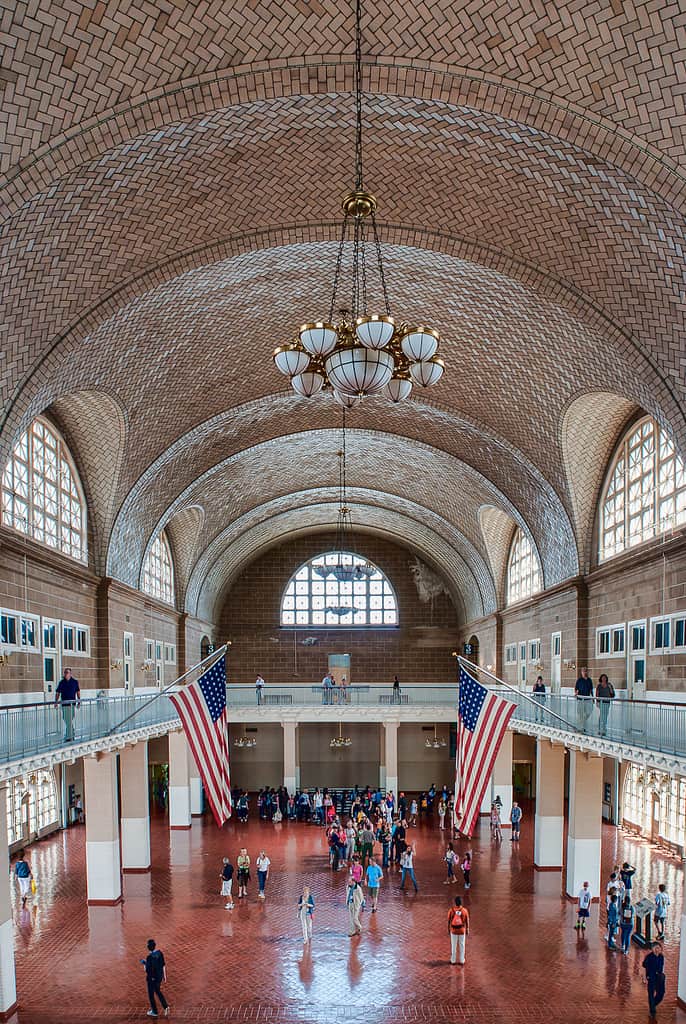

The Registry Room at Ellis Island

Though useful as shorthand, the legal/illegal binary is an utter failure when it comes to framing immigration in a just and dignified way. Such language reduces the fullness of a human life to a single category: their immigration status. Was the woman sitting before me a person shaped by her own history, unjust and graced as it was, or was she simply illegal? It’s not that this status is not relevant – it is – but the world “illegal” comes clothed with sinister connotations; the word itself conditions what we see.

We ought to admit that the hidden implication behind illegality is criminality, wrongness, violation. When we hear “illegal” we also hear “criminal,” which means that we tend to respond to immigration as we do to a crime, by using police and enforceable laws. But the law is clear, immigration is not actually a criminal issue, it’s a civil one.8 And this has consequences for us specifically in how we think about solutions.

***

So what is to be done with the two problems I’ve raised here? First, we cannot be satisfied with the current state of affairs. We cannot be satisfied with sloppy terminology, interminable delays for visas, overwhelmed judges and pre-trial detentions delays that turn into year long sentences. We cannot be satisfied. But what can we do?

We can reform the immigration courts, and in simple ways, like by providing qualified legal aid to each detained immigrant. Right now, because immigration is classified as a civil matter, immigrants are not entitled to a lawyer the way a criminal defendant is. Yet, immigration law is so incredibly complex that even highly skilled practitioners can be stymied by it (and certainly its consequences can be just as traumatic as any criminal conviction). There may very well be immigrants who ought to be returned to their home country for a variety of reasons, but deportations should only take effect fairly, which means giving defendants trained attorneys and giving our currently overwhelmed judges (remember, they have 1,200 backlogged cases each! 1,200!) sufficient time and space to decide each case well and with an eye toward our common good. Ensuring competent legal representation and adequate for immigration cases is a ready-made bipartisan solution to our immigration problem.

We can remember our own immigrant roots, too. We can let it remind us that neither immigration nor immigrants are, in themselves, a threat to this country. We can let it remind us that no problems are interminable, and that collapsing all immigrants into discussions of legal vs. illegal whitewashes fixable structural problems. Unless we’ve found a some new papyrus, Jesus never said “Blessed are those who run an inefficient immigration system, for great is the bureaucracy in heaven.” It is frustrating and deadening in the extreme when we assume that the law cannot be changed, when we view it as though it were set in tablets stone. The act of remembering and believing can remind us that there is no Eleventh Commandment that says “Thou shalt not admit more than 226,000 immigrants annually.”

On a practical level, we can make demands of our elected officials. We can insist, through letter-writing, supporting reform campaigns, even visiting with them, on just and humane reform that is people-first. The United States Conference of Catholic Bishops runs a “Justice for Immigrants” site with news, information, and an “action center” to help coordinate these efforts. Likewise, the Ignatian Solidarity Network has designed immigration as one of their focus issues for the Ignatian Family Action Month this February; they have resources available as well. Read, learn, discuss, pray. Then do something.

And we can change our starting point. A just and humane approach to immigration will not start from a particular “conservative” or “liberal” policy, or even from a question of “amnesty” versus “security.” It starts by letting ourselves hear a prophetic voice and continues in challenging both ourselves and policy makers to see immigrants as children of God first, and as “legal” or “illegal” second. We can start by recognizing our common humanity, and let that guide us toward resolutions of the real problems that our country faces from immigration.

***

When the young Guinean woman finished telling me her story and answering my few questions I took a few deep breaths to gather up my courage. I looked up at her again. It felt like she already knew there was nothing I could do. And then, looking at me, she smiled.

I looked back. How could I just dismiss her story, her life in those six words? How could they be true? I said them anyway: “There’s nothing I can do.”

Of course it’s not all I said. I also thanked her, for telling her story, for sharing with me, for letting me be part of that story if only for a moment. I told her that things could change.

She seemed to understand. Then she rose from her seat and took my hand and said “Thank you” herself. I was used to this. As a lawyer, many clients and potential clients say the same. But this woman for whom I could do nothing, she offered me a thank you for listening.

It’s only a beginning, listening, but it is a beginning.

— — — — —

- Full disclosure: I graduated from the University of Wisconsin Law School in December 2005 and practiced criminal defense and family law in the Madison, WI area before entering the Jesuits. I became involved in immigration first as a volunteer attorney for Catholic Charities Milwaukee and recently as a consultant to a legal aid office in New York. This means two things: 1) even though I know a good bit of law, I’m not an immigration specialist, and 2) I live in the sure and certain hope that heaven begins with a brat and a beer on the Memorial Union Terrace at Lake Mendota. On Wisconsin. ↩

- Since the election, we can see that both parties have focused on immigration reform for the upcoming Congress to consider. Take a look at the Democrat and Republican plans. ↩

- Quotas are set by law through the Immigration and Nationality Act, as amended. The formula can be found beginning in Section 201 of that Act. For 2012, family-based immigration was capped at 226,000. ↩

- We know these numbers because each month the State Department issues a bulletin to let us know how fast the applicant line is moving – you can find the November bulletin on their website. ↩

- The Bulletin shows that the situation for employment-based immigration is somewhat better. Most of those dates are current, although the ones that are backlogged are backlogged substantially. I.e., over an 8-year wait for Indian holders of advanced degrees, and about half a decade for most skilled workers (see category 3). We ought also to note that little of this helps the many low-income or agricultural workers, as most of the employment classifications are for skilled workers with advanced degrees. Unskilled workers are not guaranteed their own class of visas, filling instead the same category as workers requiring 2 years training or 4-year college degrees. ↩

- Which, if you’ll grant me a lawyerly aside, are not actually courts with independent judges with life tenure and salary guarantees. Immigration courts are run by the Department of Justice through the Executive Office of Immigration Review and immigration judges are appointed by the Attorney General and are his delegates to make immigration decisions. ↩

- Two points here: first, it’s notable that those waiting for trial aren’t actually classified as criminals because immigration is, legally and constitutionally, a civil issue. Second, the interactive backlog tool is available here if you want to check my numbers. ↩

- There are actually very few immigration crimes – fraud, smuggling, and re-entry after having been ordered removed, are the major ones. Even unauthorized entry is not generally a crime. And, as noted above, just under 26,000 of the 325,000+ cases pending in immigration courts are classified as criminal or security issues. The term is genuinely misleading. ↩