“To be honest,” Yunji told me, “I hardly ever speak English. I don’t have to because at the restaurant all the workers are Korean, and at home I speak Korean with my family.”

This is how our Friday morning language exchanges began. Yunji is the aunt of one of the leaders of the Korean American Young Adult Catholics of Chicago, an organization which I’ve gotten to know. Unlike some of the younger Korean Americans who were born in the United States, Yunji spent most of her life in Korea. This is her story as much as it is mine, and I could not have told it without her.

We would meet on Zoom with our coffee in hand. I would correct her writing and look for the right preposition to make her sentences sound more natural. Then I would belt out long vowels, discerning the distinctions between deo, do, and dyo. Seriously, why does Korean have so many vowels? I got used to being called Susaniim, a title given to religious people, the equivalent to Brother. People in Korea use a lot of titles: teachers are called “Teacher,” directors are called “Mr. Director,” and even waiters are frequently called “Boss.” In the beginning of our sessions, we kept it pretty basic, partly because of my limited language. “What color do you like?” Yunji would ask. “I like red,” I would reply, “but I like green more.”

She would share details about her life. This included a trip to LA to visit friends and also do a clandestine job interview with a restaurant that would sponsor her green card. We talked about our favorite foods. I sent her pictures of our house’s lunar new year celebration, which is observed across many different Asian countries. We had delicious Indonesian curry, Vietnamese noodles, and Korean rice cakes. Yunji sent back a picture of a pizza. Her family had decided to get Chicago deep dish that night, which made us both laugh. Other times were challenging.

“Everything is hard,” she wrote down for one of our writing exercises, “I feel like I am always not understanding things.”

I thought back to my own experiences as an expat in Korea, and how I tended to stick to my own English-speaking communities, because it was easier. I prayed for her at mass that night. A verbal intention. Something audible. Something defined.

One evening, I got a message on my phone: “Susaniim, I know it’s late, but please pray for me.” She told me about her frustrations trying to get a state ID card, and the lines she had to wait in and the hours she had to spend. She confided in me about wanting to go back to Korea but also the worries about what awaited her there. I was surprised, but I was also consoled to be the person from whom she wanted prayers. Another time, she asked me: “Why do you want to be a Susaniim? Why did you want to become a Jesuit?” I struggled to find the words in a language that was not my own. “I … together … God … want. People … also … together … every day… with God … is….”

My grammar was lacking.

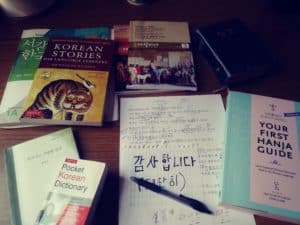

Resources the author uses for the language exchange with his friend, Yunji. The text in the photograph reads, “Thank you.”

The Korean language also has levels of formality, a source of frustration for the causal learner. However, for me the levels of formality proved to be a source of consolation. In one session, Yunji said to me: “You don’t have to speak to me with formal language. We are kind of like friends, so you can use informal language, susaniim.” Had I gotten to know this stranger so well in just a few months? It was one of those moments that made me appreciate the kind of experience these Friday morning sessions allowed me to have.

After the March shooting in Atlanta where eight people including six women of Asian descent were killed, we didn’t talk about it. I did not know if Yunji wanted to talk about it. I didn’t know if it was on her mind as much as the news suggested. It seemed to be a watershed, throwing light on years of anti-Asian discrimination and violence. It is a violence that is ongoing, as we learned last month when Yao Pan Ma, a 61-year-old Asian immigrant living in New York was assaulted and left on a ventilator and in a coma.

For my part, the March shooting and ongoing violence was not surprising. As I traveled from New York City to rural Pennsylvania last summer, I heard conservative attack ads on the TV and radio making disparaging and racist remarks towards Asians. And I felt paralyzed. I did not know what to do. I didn’t even know if it was my place to do something. “Just stand by our side,” was what one Vietnamese American Jesuit brother told me, that way we can feel supported. And that got me thinking that while I may not know what Asian Americans are going through, I can still be an advocate. I can still work towards making their voices heard.

“I want to write a blog post about you. About our exchange,” I said to Yunji during one of our Friday sessions, “if it’s okay.”

“It’s okay,” she said.

And we talked. We talked about her favorite aspects of American culture. No one asks you about your age. We talked about what scared her. People can buy guns so easily. We talked about her favorite ice cream flavor. Chocolate, but really, I like them all. I asked Yunji what she thought about all the incidents of anti-Asian violence. First, I was so scared and sad, but then I got angry. Honestly, I think those people who attack are just ignorant of Asian history. I asked her about living in Chicago. As you know, Chicago has a high rate of gun related crimes. So, I feel a little bit of danger. However, the racism in the United States is quite similar to the racism in Korea. Korea can also be racist against other Asians and Black people. I asked her how she felt in Chicago as a woman, and she said she never thought of that before. I messaged her what she would change about the world if she could and what her hopes were for the future. I would like to change the Amazon rainforest back to how it was 100 years ago. And as far as the future, I really just want to find my way. Susaniim, please pray for me.

I did pray for her, that she would find her way some day. What I learned from my language exchange has been more than words and sentences. It has been more than grammar and pronunciation. I have learned how to talk to someone, someone with different life experiences. It’s something I continue to learn, how to speak and how to listen. Prayer is also like this. We learn to speak to God, and we learn to listen to God. However, we cannot go into the dialogue with our own preconceived notions, with our own scripts. We cannot dictate how the conversation will go. Sometimes God just may surprise you, just like Yunji did when she asked me to pray for her and invited me into this friendship that transcends language and cultural divides.

-//-

Photo by chahn chance on Unsplash