“Bro! Tell me we still know how to speak of kings!”

What a wonderful first line in Beowulf: A New Translation by Maria Dahvana Headley. There is something epic about the call to remember, and something earthy about beginning that call with a word like “bro.” This opening line, then, represents the story of Beowulf as a whole: it is indeed an earthy epic. Headley’s translation provides an opportunity to enter into this old story with fresh eyes. This new perspective vivifies the tale for me, and leads me to reconsider some points in my faith life.

Written in Old English in the late 10th century, Beowulf is a poem which has been translated again and again through the centuries. Like many people, I first read it in highschool. It was a tale of warriors and monsters, kings and witches and dragons. Even so, it was difficult to connect with the world it described – even for a teenager who read his share of fantasy novels. If it was difficult for me to connect, many of my classmates were downright bored with it. How can a story so full of action result in so many feelings of “meh” in so many students?

This brings us back to “bro.”

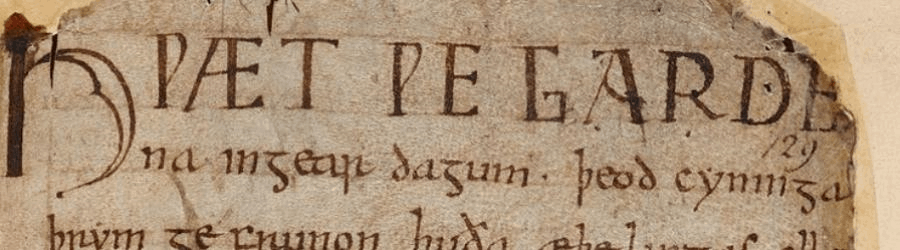

The first word of the poem – in Old English: Hwaet – is an exclamation often translated as “Lo!” or “Hark,” but which Headley renders as “Bro!”. Her argument is that this term relates the sense of that exclamation in the context in which it was intended, and thus allows current readers to understand the place and the meaning of the story as a whole.

But what, we may wonder, is the context in which Beowulf was intended to be read? Well, it probably wasn’t meant to be read at all (at least not by most people): Beowulf was meant to be heard. More than that, as Headley discusses in her excellent introduction, this poem was meant to be shouted over raucous voices in mead halls.

The disinterest felt by modern teenagers in such an action-packed story may be due in no small part to encountering translations which, in presenting a more polished, high romantic tenor to the story, sever Beowulf from the wildness of its context. Headley’s translation – with its mix of slang (“bro”), meme (“#blessed”), and poetic alliteration reflecting the Old English style (“a tapestry of terror threaded with triumph”) – revels in this wildness.

While much attention can be paid (and rightly so) to Headley’s eclectic word choice in this translation, it is in how these choices animate the story of Beowulf which caused me the most reflection. Here are some ways in which Maria Dahvana Headley’s Beowulf: A New Translation has given grist to my faith life.

Fate or Providence?

The basic plot of the Beowulf story is rather straightforward: a young and remarkably strong warrior with a shipful of companions frees a neighboring kingdom from a pair of monstrous enemies, establishes his own kingdom, grows to an old age, and finally defeats a dragon, though soon after, dying of his wounds.

Throughout the story is the looming presence of fate. Before each major battle, there is reference made (sometimes by Beowulf himself) to accepting the outcome of the fight as being pre-ordained (whoever’s time it is to die will lose the fight). On top of this, however, was the belief that God would act to aid or hinder people in accord with His own plan. On more than one occasion, when it looks like Beowulf may lose a fight, it is said that it was God’s favor alone that allowed him to recover and emerge victorious.

Fate and providence, though they may sometimes feel like they are the same thing, have one crucial difference. Fate is inscrutable and uncaring: all things happen as they will and there is no greater purpose behind it. Providence, by contrast, refers to the overarching plan of God (that is, the plan of salvation) being laid out in the lives of people.

So much happens in our lives that is beyond our control. Do we see such things as random and unfeeling, or do we recognize the hand of God guiding us through them?

What makes a good person?

The heroes of ancient epics were not always good, in our modern understanding of ethical care and moral living. They could be vicious, greedy, and vain. They could also be tragically misguided. Beowulf lived in a world in which loyalties were bought with gifts of gold, bravery was inspired most of all by a desire to be remembered, and the brutality of life was met with a corresponding brutality.

In her introduction to the story, Headley allows that “Beowulf is a manual for how to live as a man;” but this is the case only “if you are, in fact, more like the monsters than the men.”

How often do I act to act publicly so as to be remembered? Do I offer gifts with strings attached? Do I justify treating others poorly because they treat others poorly? In other words, am I content to treat monsters monstrously?

How do we read Scripture (or anything else)?

Finally, let’s return to the translation itself. Headley’s guiding principle – presenting Beowulf in language that reflects the context in which it was originally composed and presented – offers us an opportunity to reflect on how we read Scripture.

Do we place more importance on the words of translations written in specific times, in an idiom appropriate for their time if not for ours, than on the meaning with which they are meant to move our hearts? Are we more concerned with “getting it right” in the particular images and expressions than in receiving what those very things try to convey?

Accurate translation, for Beowulf and, certainly, for Scripture, is important. This is not to advocate a free-for-all approach to use any words we want to make the meaning anything we want. At the same time, works such as Headley’s Beowulf remind us that truth, beauty, and goodness are always relevant and exciting – and are more important, ultimately, than the specific ways in which we try to express them. The Word, after all, speaks more eloquently than any words.