Multiple hurricanes have battered the Gulf Coast and wildfires continue to ravage California and Washington. A global pandemic continues to wreak havoc. The realities of racial injustice and the cry of those who will no longer be quietly victimized ring out more and more loudly. Political discourse deteriorates and partisan fragmentation worsens, especially as we pick up the pieces from an election that reflected the deep level of division in the US.

Is now the time to think about C.S. Lewis?

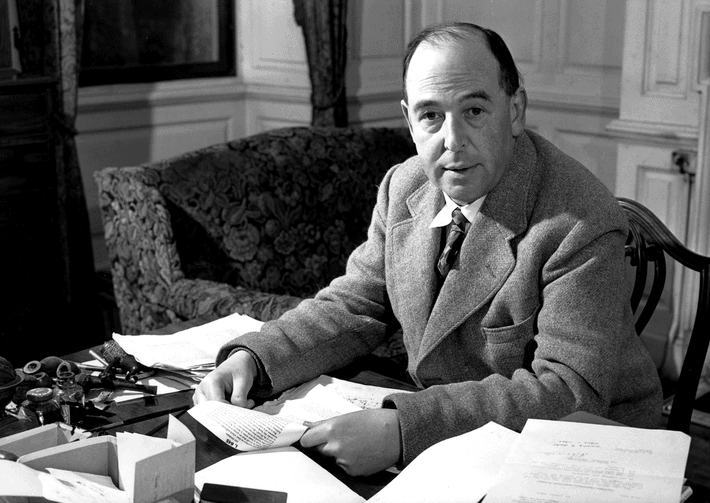

In a recent article for America Media, Thomas Harmon argues that our current era of uncertainty and fear around COVID is an opportune time to read Lewis, who spoke and wrote during the time of uncertainty and fear that was the Second World War. Even so: Is now the time to consider C.S. Lewis’ thoughts on literary criticism? Truth be told, I am not sure, even as I write this.

Several years ago I went on a bit of a writing kick and came across some of Lewis’s essays on criticism. I jotted them down in my journal and have periodically returned to them, increasingly so in the last several months. It seems to me that we need as many sources of inspiration as can be found in order to overcome the manifold crises which surround us.

Here are nine rules for literary criticism that Lewis laid out in his On Criticism (published posthumously in 1975). While directed to those who would criticize fiction, they provide helpful reminders for us as we engage in a reality that can so often seem unreal.

1) Honesty

“One mustn’t tell lies,” writes Lewis. It is as simple as that. Yet how tempting it can be to suppress parts of the truth in, for example, our social media posts. Perhaps we feel as if the deeper point we wish to communicate gets “lost” in too many facts or too much context. Perhaps we post or promote what others have written without considering how the truth is used or presented. Being honest means being honest: neither suppressing part of the truth nor using facts to suggest what is false.

2) Read Carefully

Lewis cautioned would-be critics to only write in their reports what could be supported by the specific work they were reviewing. When we read a post from someone we know well or follow frequently, or when we read an article from a news source whose outlook and biases we feel we understand, this can be easy to forget. We can easily fall into imposing a background onto a piece that does not actually belong there. Read what is written and judge based on that.

3) Be Careful About Assuming Historical Influence

It can take a long time for a written work of fiction to make its way through the publishing and printing process. Depending on the book and the publisher, years could separate the writing of the work and its availability on store shelves. For this reason, Lewis would caution critics not to read contemporary events too easily into a work of fiction – even if they seem to fit . What seems immediate and newly relevant may in fact have been going on for some time. Perhaps we should exercise similar caution in casting the entirety of blame onto current individuals for broad and complex social ills.

4) Do Not Psychologize

Most of us are not psychologists. Those who are trained psychologists tend to rightfully shy away from diagnosis from afar. Lewis reminds those who would judge the words of others not to attempt analysis on the author’s subconscious. It can be difficult enough to correctly identify my own motivations and inner feelings, and even those closest to me remain personified mysteries. How much more so the protester, the reporter, the politician on the other end of my screen? As with Rule 2, we must rely first and foremost on what is said and written, not on some meaning we think we can identify lurking in the background.

5) Check Wording

When we seek to post, to publish, to speak we have a duty to make sure to mean what we say. It is an easy trap to fall into using sarcasm and protestations of humor to cover a slip of the tongue (or pen or keystrokes). Taking the time to consider our words allows us to speak with sincerity and to therefore be taken at our word. This is a high bar. It is therefore equally important to be gentle with ourselves and with others when what is typed or said is later clarified or recanted. We all make mistakes. A brief pause before hitting “post” may not prevent mistakes, but it will make them less frequent (and our contrition for them more believable).

6) Criticize the Content, Not the Author

Lewis uses Aristotelian categories for this, reminding the critic to be concerned with the Formal Cause (what makes an argument bad) and not the Efficient Cause (why the speaker made a bad argument). It is also called an ad hominem argument: ignoring the words and attacking the one who made them. How commonplace this is! Perhaps the greatest temptation here is to respond to an attacker with attacks. We are tempted to treat others the way they treat others, instead of how we wish to be treated. If we wish to be heard, to be taken seriously, then we must offer others the same courtesy.

7) Remember the Difference Between Intention and Meaning

So far these rules have emphasized the actual argument of the post, article, or speech we encounter and cautioned us to ignore backgrounds (real or imagined). Here Lewis notes the distinction between an author’s intention in composing their work, and the meaning that work has once shared with others. An author is in control of their own intention, not of the meaning of their work. While we must carefully avoid presuming intent (remember Rule 4), once a post or article is shared, the context of the times and of the past statements of the author give shape to its meaning. And the meaning is important! (We could say, even more important than the intention.) Remember that the importance of meaning goes both ways, however. When we write or speak we cannot control the broader meaning of how it will impact others. This does not absolve us from the responsibility to listen.

8) Consider the Surface Meaning Before Going Deeper

If any author knew about allegory, it was C.S. Lewis, the author of the Chronicles of Narnia. He cautions critics that just because something can be read as an allegory, does not mean that it is one. In other words, the author’s intent may have been to say only what they said, without hidden meaning. This does not mean that there is no hidden meaning which affects others. When this happens, it is important to remember Rule 5.

9) Criticize Most What You Know and Like

This may be the most difficult of all. When it comes to books, Lewis notes that no critic should judge a work in a genre that they do not enjoy. Each genre has its own style and rules. A literary critic should only judge those works which belong to a genre whose rules they know well and in which they only wish to see the best. Perhaps we should focus our most frequent criticism not on those with whom we disagree, but on those whose projects we agree with and whose good we are most eager to see. This requires a shift from placing our energies on seeing enemies defeated to seeing friends and neighbors succeed. If we are honest and sincere in this pursuit, we may find a startling and beautiful truth: we have far fewer enemies and far more friends and neighbors than we first thought.