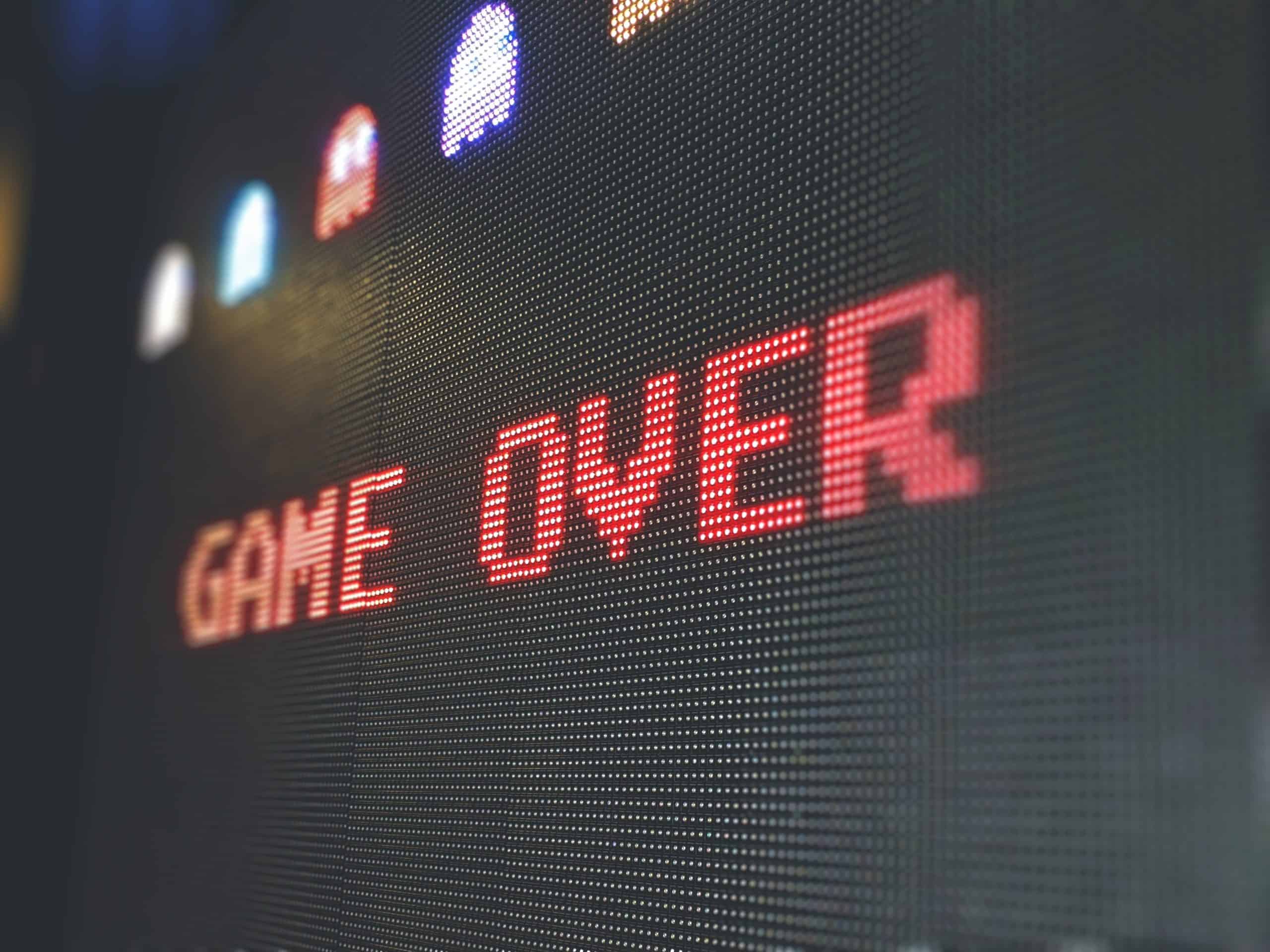

If you are like me, sometimes it can seem like the commitment to antiracism is a game in which I first have to prove that I am on the right team, then continually score points in order to “win”:

Watching an antiracist retreat video – 20 points

Catching up with a friend of a different race – 10 points

Saying “Black Lives Matter” – 2 points

Carrying How to Be an Antiracist around – 50 points

Actually reading How to Be an Antiracist – 500 points

Attending a demonstration – 250 points

Voting Democrat – 1,000 points

The goal isn’t actually eliminating racist structures or empowering disenfranchised persons, but rather proving to everyone around me that I am antiracist.

Perhaps the strongest play in the false antiracism game is the “cancel”. If I call out and shame someone for doing something that could potentially be considered racist, that secures me the upper hand and gives me some temporary immunity from the same fatal accusation. When someone gets “cancelled”, the point is not to call out their racist action or idea (true antiracism), but rather to eliminate them from the game and assert my superiority.

Thinking of antiracism in this way is just another way of saying “I am not racist.” According to Professor Ibram X. Kendi, author of the bestseller How to Be an Antiracist, using “racist” as a pejorative and defensively avoiding it is actually a tactic of White supremacy. Antiracism is not a rejection of racist people, rather it “locates the roots of problems in power and policies” (not “groups of people”) and seeks to dismantle them.1

Kendi goes on to say that it is common for people to think that racism is rooted in ignorance and hate and that education is the solution. But his research led him to the insight that “the source of racist ideas was not ignorance and hate, but self-interest”:

The history of racist ideas is the history of powerful policy-makers erecting racist policies out if self-interest, then producing racist ideas to defend and rationalize the inequitable effects of their policies, while everyday people consume those racist ideas, which in turn soaked ignorance and hate.2

Therefore, to combat racism, one must focus on policy change over mental change.

Redistributing power and changing policy is hard. It takes work and time and maybe can’t be distilled into Instagram posts. It’s much easier to play the game of false antiracism.

To move past playing the game, I must first confess that I often think of antiracism this way. For me, confession flows from a place of trust in God and confidence in forgiveness and redemption. Once I experience the freedom that comes from this confession, I can more genuinely participate in the necessary work of building authentic communion by loving my neighbor and actively promoting antiracist policies, rather than avoiding my own sin by pointing out others’.

-//-