What do you call someone who teaches classes, grades materials, lectures, guides labs, facilitates study groups, and completes thousands of hours of research while also studying and writing theses or dissertations? According to most universities, you’d call that person only a student. According to the grad students themselves, they’re also workers. And these workers are seeking to unionize.

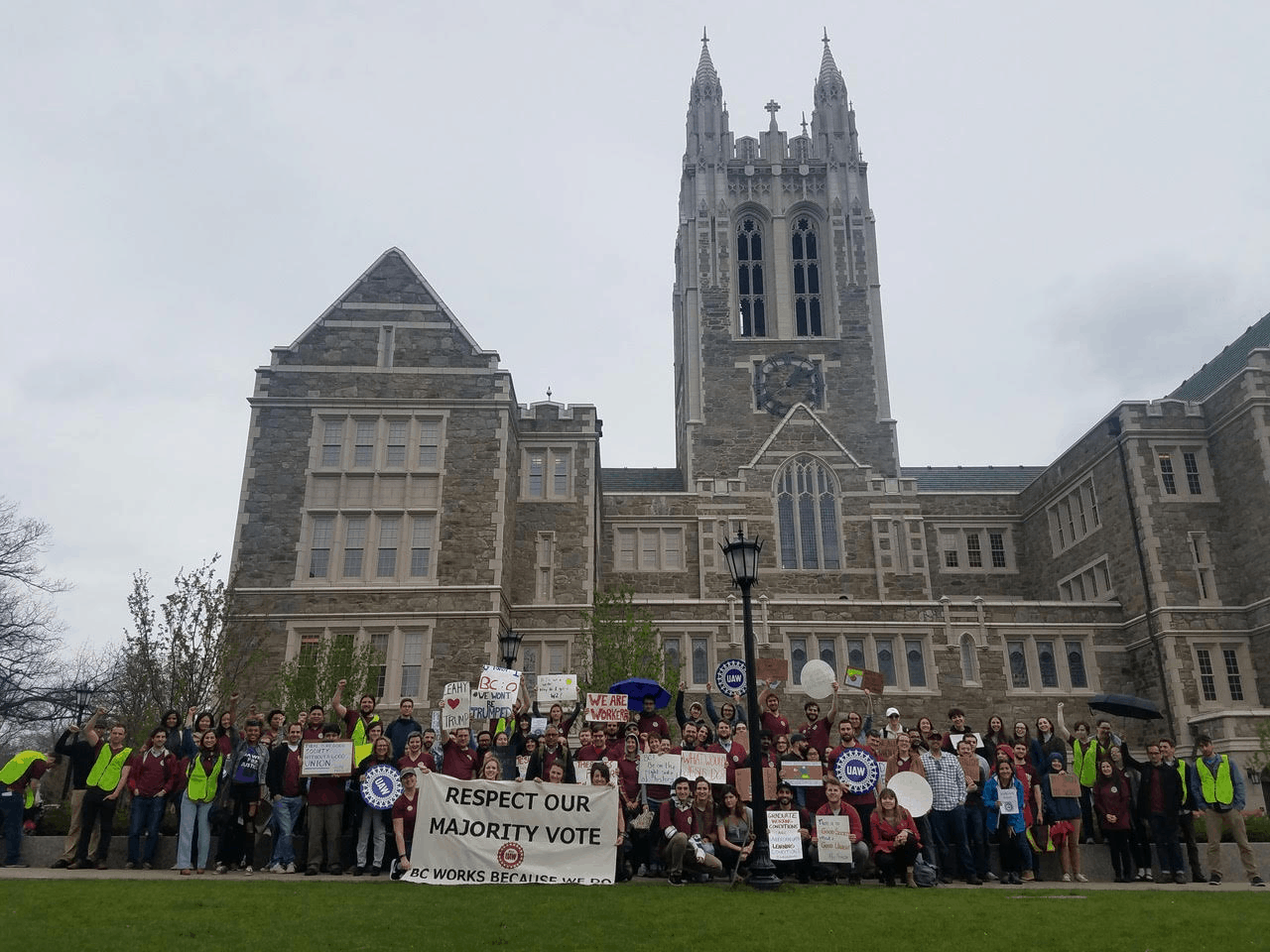

Graduate student-worker unionization efforts have been gaining steam over the last five years, perhaps mostly prominently at Columbia University. In the Jesuit world, efforts to unionize are underway at Boston College, Loyola University-Chicago, and Georgetown University, with workers at several other Jesuit schools considering unionization. These efforts raise several important questions related to Catholic Social Doctrine, some we are only recently addressing: How do we define work and workers? How do we ensure justice for workers? How will the changing face of higher ed impact justice for workers?

Are they students or workers?

Many argue that graduate students are just that: students. Their primary objective is achieving a higher level degree. But graduate workers take on many of the same responsibilities as professors. In the words of Jason, “We keep the university running by teaching classes, serving as a teaching assistants, and also performing research on behalf the institution. Literally two important and essential capacities of a research institution would not be done were it not for graduate students.”1

Some might argue that graduates are simply learning to do what professors do, modeling and copying them. Therefore, they are students. This argument proves rather flimsy. For one, many graduates perform research and teach on behalf of a professor; in other cases, they are fully in charge of entire courses or research projects with no professorial oversight. For another, this argument operates under the assumption that being a student and a worker are mutually exclusive.

Michelle, a member of one graduate union, wonderfully sums it up:

“I am a worker because I receive monetary compensation for performing services that are vital to the functioning of this university, and because the IRS considers me to be an employee of Boston College for tax purposes… It is logically inconsistent and morally reprehensible for the university to consider me an employee when it is convenient (or legally required) for the administration to do so, but to consider me to be “only a student” when it is inconvenient for them to acknowledge my status as a worker.”

From a Catholic vantage, work is not simply what one does to earn a wage. Rather, it is the ongoing participation in God’s creation. In his encyclical Laborem Exercens, Pope St. John Paul II intentionally broadened the definition of work to “any human activity, whether manual or intellectual, whatever its nature or circumstances.” Clearly, then, one can be both a student and a worker, especially one deserving adequate pay.

Why do workers want to unionize?

Graduate workers face a number of challenges and injustices. Wages (typically called stipends by the university) fail to keep up with cost of living and occur irregularly. At Loyola-Chicago for example, some graduate students are paid $2,000 per month only nine times per year. One psychology student, Kelsey, stated that she is sprinting through her program to control costs, leading to a significantly diminished education. For international students, visa regulations ban them from seeking additional employment. At some schools, professors and administrations have (illegally) threatened to revoke their student visa status if they participate in unionization.2

Other pressures include: affordable access to better healthcare coverage; freedom from retaliation by the university and unjust termination; third-party protections against sexual harassment; protection for undocumented students; and addressing racial injustice and hatred on campus.3

Allison beautifully articulates why she is unionizing:

“Let’s take a step back: if BC was behaving in a Catholic-Jesuit manner, then we wouldn’t be forced to join a union, because BC wouldn’t exploit this workforce so cruelly. I’m not just talking about us being underpaid. I’m more talking about the insecurity it brings about not having a binding contract with your employer. I believe it goes against the teachings of the Bible to subject your fellow humans to such insecurity. Thus joining a union is doubly a Catholic-Jesuit choice because on the one hand we act following the Bible, and on the other we remind BC to do the same.”

Why do universities object to unionization?

Just as with adjunct faculty organizing, universities have fought back against the unionization process. In several letters from Boston College, the university administration has made it clear that they believe unionization to be disruptive to the learning process and to the university mission.

In a January 2018 letter, Boston College argues that the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) made a mistake in identifying Columbia University graduate workers as employees; and that the NLRB should not have jurisdiction at BC because of religious exemptions. They worry about NLRB interference in living out the schools Catholic identity. The NLRB, however, has declared that the religious exemption only applies to theology departments and that it does have jurisdiction in non-religious departments (chemistry, history, etc.).

In a September 2018 letter, Dean Quigley states, “Our position remains that graduate student unionization in any form undermines the collegial, mentoring relationship among students and faculty that is a cornerstone of this academic community.” Contrastingly, BC student Arthur states, “Yes, it might ‘undermine’ a faculty member’s ability to make their graduate students work 60 hour weeks, but that is a GOOD thing. I think it would actually improve many mentoring relationships for mentors to understand the limits of what they can ask students to do.”

How do we proceed?

Universities find themselves in a growing bind. Costs are increasing, but they cannot simply continue increasing tuition. There is tremendous competition among universities, especially given the sharp drop in humanities bachelors and spike in STEM. Liberal arts colleges – particularly smaller and Catholic schools – have been closing at an increasing pace. It is unfair, however, for universities to push these economic challenges onto graduate workers.

Rather than reject graduate unions out of fear for what might happen, Jesuit universities should embrace them for what could happen. For example, as the Association of Jesuit College and Universities lobbies for reauthorization of the Higher Education Act, increased scholarship funding, and protection of undocumented students, it could collaborate with local unions. Together, unions and universities might provide vital job and pedagogy training. They might transform their local communities and the face of higher ed.

Jesuits have historically been leaders in higher education. When they have become complacent, both they and their universities have drastically weakened. By willingly participating in collective bargaining and unionization, Jesuit schools can demonstrate a commitment to pursuing justice not only for their own employees, but throughout the higher education system. It is time for Jesuit schools to imagine, collaborate, and lead.

- All names have been changed. ↩

- Students provided feedback via anonymous survey and personal interviews for this essay. This was an injustice that came up several times in their accounts. ↩

- For an in-depth look at what graduate workers ask for in a union-backed contract, see this highly detailed list from Columbia University’s graduate union. ↩