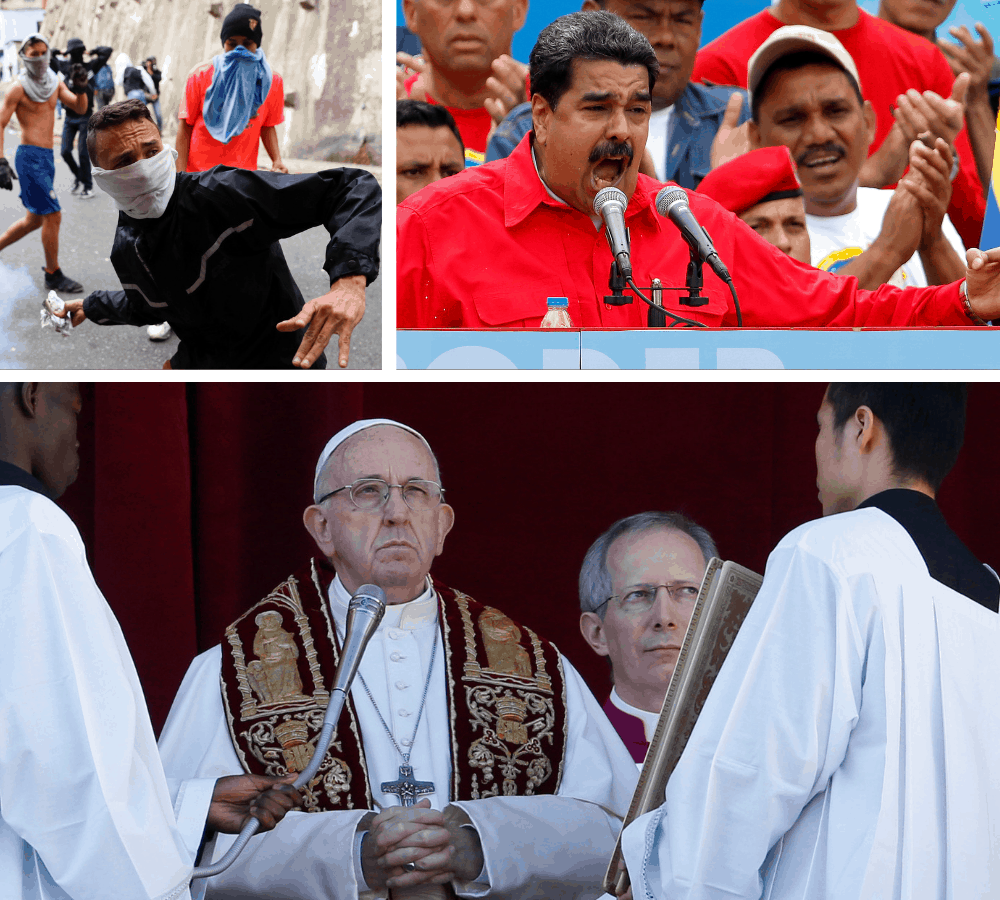

While all eyes have been on the sex abuse summit in the Vatican, other stories have been playing out, as well. Amidst turmoil in Venezuela, all sides have called for Pope Francis to mediate, even as the country’s embattled former president has rejected U.S. intervention.

In recent weeks, both Nicolás Maduro, the recently-re-elected but disputed president of Venezuela, and Juan Guaidó, the internationally-recognized interim president, have requested that Francis mediate a solution.

International pressure, however, could force Maduro out before any such diplomacy could be effective. The United States, much of Latin America and Europe have declared Maduro’s re-election illegitimate, while Russia, China, Cuba and Iran among others have stood behind Maduro.

In any case, I want to tell the story of recent Vatican diplomacy in Venezuela. Though it hasn’t been a success, it’s still a worthy story.

Thin Ice

Tensions run high in Venezuela. The current humanitarian crisis has unfolded over several years. According to the United Nations High Commission on Human Rights, over 3.4 million Venezuelans have emigrated, mostly to Colombia, Peru, Chile, and Ecuador. Violence has increasingly become part of everyday life; government-created death squads are a reality.

But the ongoing standoff over humanitarian aid and the Trump administration’s involvement at the Colombian border have left behind-the-scenes diplomacy out of the news cycle.

The Vatican has been strategizing for several years on how to approach the crisis in Venezuela. It’s the kind of diplomacy that requires very careful steps: if the Vatican delegitimizes Maduro, it loses any sway over him in the future. If there’s no critique of the government, the Holy See abandons the Venezuelan Church.

In 2016, Francis opted to name Baltazar Enrique Porras Cardozo, Archbishop of Mérida and Apostolic Administrator of capital-city Caracas, a cardinal. It was just the right in-between. The red hat gave Porras a bigger microphone while letting the Pope keep some distance from direct and public critique.

But the optics have still been tricky: some have perceived a rift between Francis and the Venezuelan bishops, or at least noted that Francis has not taken sides, but simply reiterated his desire for a solution.

As Boston College theology professor Rafael Luciani puts it, “Local bishops have the responsibility of political particulars and ethical positioning in the face of [dictatorial] regimes.” According to Luciani, the Vatican has never branded a president as a dictator since 1939.

Some perceive a good cop-bad cop game: local bishops apply the pressure, while the Pope maintains a position to negotiate from.

So after years of work, where are the results?

“Señor Maduro…”

Though Francis reiterated his desire for a peaceful solution in Venezuela at the end of January, it was Maduro who reopened the door to negotiations. In the first days of February, he asked the Holy Father to mediate a solution. Both Maduro and Cardinal Pietro Parolin, the Vatican Secretary of State, made that public on February 4.

And the following day (on his flight home from Abu Dhabi), Francis announced that he would be willing to mediate — but only if “the will of both parts” was a real mediation.

Less than a week later, Guaidó also reached out.

As his team was in Italy on February 11 seeking lobbying for recognition, they also met with representatives of the Vatican Secretariat of State. Though Vatican involvement in diplomatic solutions had not produced results in the past, it seemed there was some hope for progress.

But then a letter from the Pope to Maduro went public.

Dated February 7, it was not a sign of progress. Not only did Pope Francis omit the word “president” in addressing Maduro (a new development), but he said that mediation would be impossible. “Unfortunately all the attempts [of meditation] have been interrupted because what was decided in the meetings was not followed by concrete gestures to accomplish fulfill [previous] agreements,” wrote Francis. The Maduro regime had already disqualified itself for acting in bad faith, at least until it could show a willingness to follow-through.

At the time of this article’s writing, the Colombian and U.S. governments were attempting to deliver humanitarian aid, with the U.S. government officials continuing to make regular calls to the Venezuelan military to defect. It seems time is up for any peaceful Vatican-mediated solution, as the likelihood of armed conflict continues to increase

The Reconciling Papacy

Pope Francis’ potential mediation in Venezuela is not surprising.

Since Paul VI left the confines of Vatican City in 1964, the Vatican has taken on a new role in the world. The pope’s ministry of public reconciliation and political mediation has not been a mission of neutrality, but an active, non-partisan desire for the well-being of all involved. That is, non-bloody solutions in favor of the people are to be preferred. (Unlike democracies from the global north, the Vatican has never been accused of using its influence and staging an intervention to gain access to oilfields or other natural resources.)

A significant part of Saint John Paul II’s legacy was one of public expressions of remorse on behalf of the Church. But JPII also mediated intense political situations, like in Pinochet’s Chile and the Dirty Wars of Argentina.

A papal visit is still received almost everywhere as a sign of peace, though sex abuse and cover-ups threaten to undermine the Vatican’s ministry of mediation, as was the case in Francis’ visit to Chile last year.

Behind the Scenes

Diplomacy does not always bring resolution to political crises, and it will probably not change Venezuela’s current crisis. But as a Catholic I take some comfort in knowing that the pope is quietly working to make the world a better place with whatever influence and credibility he has.

With the end of the recent meeting of bishops on sex abuse, real work can hopefully be done within the Church to show real commitment to eradicating abuse and finding a credible path to repentance and healing within the hierarchy. Yet there is also much work to be done in civil society: bishops in Venezuela and Nicaragua find themselves pushing for peace with whatever Vatican backing they can get.

I’m not sure how long the ministry of mediation will continue if bishops cannot instill confidence that they are protecting the flock, but for the time being I’m content to reflect on an image I heard in a hymn here in Lima, Peru: “Es hermoso ver bajar de la montaña, los pies del mensajero de la paz.”

“It’s beautiful to see the feet of the messenger of peace coming down from the mountains,” even when the offering of peace is refused.