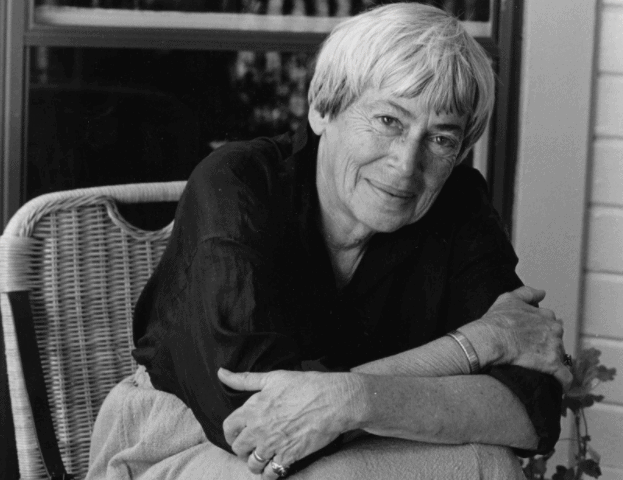

In such an oversaturated and overstimulated media environment, filled with abuse, neglect, anger, and fear, it would have been easy to overlook a short announcement on January 22 that the author Ursula K. Le Guin had died peacefully at the age of 88. That would have been no surprise to Le Guin, who had given pride of place in her tales to overlooked peoples, places, and cultures.

Le Guin, whose works include the Earthsea Books, The Left Hand of Darkness, The Dispossessed, The Lathe of Heaven, and the short story “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas”, was a master of multiple genres and forms, with acclaimed novels in fantasy and science fiction. An anthology of her works were included in the Library of America series while she was still living, a rare honor that she shared before her death with few others.

But to say that she was a well-awarded author is to miss the point: Ursula Le Guin was, first and foremost, a good writer. In every sense of the word, Le Guin was a master of her craft. In her works, Le Guin generated complex characters, devised subtle plots, and created broader landscapes and worlds for her characters to traverse. Her mastery is evident even at the very basic level of the sentence, for much of her prose can, in its elegance and simplicity, mirror the best of poetry. Le Guin’s words greatly repay being read aloud.

Those traits Le Guin shared with many other great writers. Le Guin’s goodness as a writer extends to how she employed her mastery as a writer. The daughter of anthropologists, Le Guin brought an anthropologist’s eye for the ways and customs of a people, understanding how characters and stories emerge from a culture. This allows Le Guin to imagine the institutions of culture and society differently. She employs this most famously in The Left Hand of Darkness, in which the residents of the planet Gethen are without gender except for brief moments of the year. Le Guin asked questions about people that others didn’t and her fiction possessed incredible depth as a result.

Le Guin embraced the responsibility of the writer to tell others’ stories with respect and care, recognizing that what she wrote did not solely belong to her. This trait Le Guin observed first in her father, who studied Native American culture in northern California and worked side by side with native peoples to preserve as much memory and culture as possible in the face of white intrusion and the culture churning effects of industrialization and modernity. Thus, Le Guin felt compelled to tell stories that, in her words, reflected both sides of the frontier, the side “where no one has gone before” and its opposite, the side “where you live”, where “you’ve always lived”, no matter who you are or from what people you come. Le Guin always viewed the recording and telling of stories as a very human act of solidarity, seeking to use her gifts to tell stories of communities that lived in what she called “the wreck of cultures.” This moral seriousness lived on every page, even in her more lighthearted works, a moral seriousness that sought always to uplift the outcast and the overlooked.

Ultimately, Le Guin embraced the power of the imagination to subvert our expectations of what it means to be human and challenge us to look at ourselves in a vast different way. As she wrote, “Imagination, working at full strength, can shake us out of our fatal, adoring self-absorption and make us look up and see—with terror or with relief—that the world does not in fact belong to us at all.” It was not for nothing that her heroes were usually women or persons of color, a remarkably bold decision when Le Guin began publishing in the 1960s and 70s. Yet, Le Guin never wrote didactically: her writings provoke reflection but never at the expense of her art. She managed to simultaneously delight, teach, and move, which is the mark of the truly great artist.

In the end, I hope I have convinced you to take a look at some of Ursula Le Guin’s writings. If not, I trust I have shared with you my love and affection for a great American writer, who deserves recognition and remembrance for her decades-long work writing and seeking to discover “other ways of being, and even imagine real grounds for hope.”

Ursula K. Le Guin, rest in peace.

-//-

The cover photo is featured courtesy of Oregon State University and was taken by Marian Wood Kolisch.