Tomorrow our Church celebrates St. Peter Claver (1580-1654), patron saint of, among others things, African-Americans.

But for me, and I suspect for not a few Black Catholics, Mass on September 9th has the same unsettling feel of the first day of Black History Month. At best, the tip of the iceberg of our history will be briefly revisited. At worst, this history will be inaccurately presented.

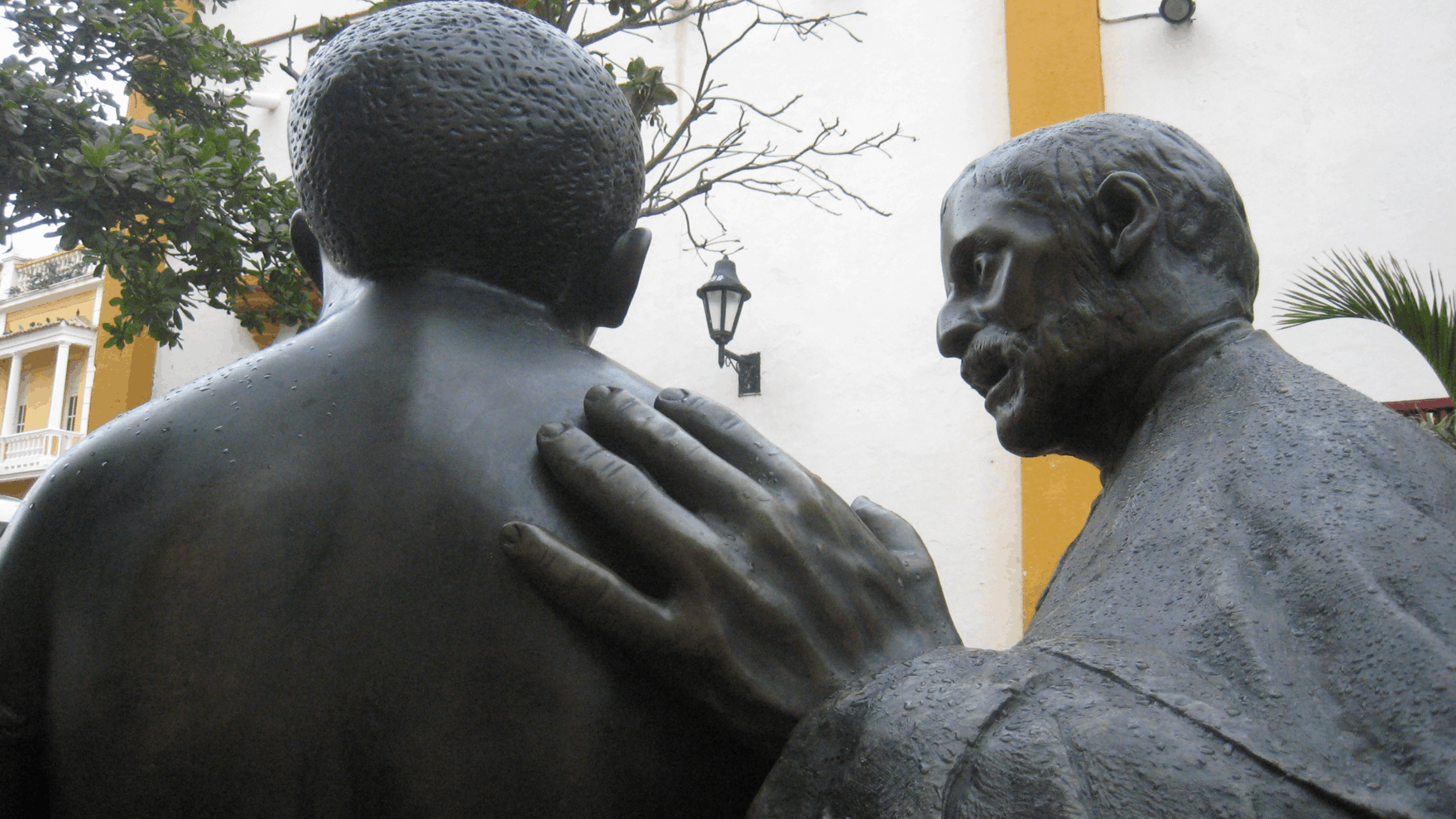

Researching the life of St. Peter Claver gives me the same feeling. Many sources rightfully laud his tireless efforts among African peoples in Colombia. Called “slave of the slaves,” he did the work that few or none wanted to do. But though Claver did much for the Africans he encountered, he never worked to end the system that held them in bondage nor was he a pioneer for racial justice or equality.

Despite that, Claver’s life is often revisited as a model for addressing our contemporary racial tensions. But trying to mold him (consciously or not) into fitting that narrative is problematic because this is not what Claver’s life and work was about. Though his efforts should not be ignored, we have an obligation to also learn the full story of what happened, who was involved, and what legacies remain. Only in such a spirit of truth can we hope for healing today.

St. Peter Claver’s story in context

African enslavement had existed in South America for over a century before Claver’s arrival. One of the earliest advocates of the institution was Bartolomé de las Casas. Las Casas had taken part in atrocities committed against Native peoples but would later reverse his position and push for Native rights and freedom. He advocated instead for Black enslavement as a replacement for their labor. Las Casas eventually entered the Dominicans and there wrote that he’d “repented” of the mistake of supporting Black enslavement as well and realized that the enslavement of any group was wrong.

This raises an interesting question: Was enslavement a universally accepted way of life of the era? De las Casas’ conversions, as well as the long history of enslaved resistance and the abolitionist movement, seem to indicate the answer to be no. Still, as las Casas had done, many continued to interpret Just War Theory 1 and the “curse of Ham” 2 as reasons enough to legitimize African enslavement.

Like many Europeans of his time, Claver functioned within these beliefs. According to a biography, it was thought that Claver felt, for Africans, “that it was better to die a Christian slave in Cartagena [Colombia’s major port] than a native chieftain in the Congo.”3

By Claver’s time, the Spanish Jesuits had taken the lead in evangelizing enslaved Africans in South America. The Africans were in terrible conditions as about 40% died between initial capture and arrival in the Americas. Thus, not only were theirs spiritual needs, but also physical ones. The ministry was intense work. In his efforts, and with the critical help of Black translators, Claver baptized over 300,000 people. He was also noted for his unique compassion and his singular ability among the Europeans to endure work in the deplorable cargo holds of the ships that enslaved people were forced to live in for months. By his death, from his contracting one of the many diseases common among the enslaved people he ministered to, Claver’s dedication had become well known as many flocked to the house where he died.

And for his work, Claver is worthy of a certain degree of veneration and imitation. He was a man who was deeply moved by the conditions endured by Africans, the poorest of the poor. Yet his good intentions were never turned towards ending the cruel system that fueled Black suffering. It would not be until 1839, almost two centuries after Claver’s death, that Pope Gregory XVI would condemn the trade of enslaved Africans.

“Don’t call me a saint [yet]”

Dorothy Day, co-founder of the Catholic Worker movement, is often quoted as saying “don’t call me a saint, I don’t want to be dismissed that easily.” I think that when she said this, she was sensing the focus wrongfully shifting from the unjust poverty in which she was immersed to herself.

This tends to happen with Claver. It’s tempting to gloss over truths of his life and era to instead move on quickly to something else because we get uneasy talking about racism. It’s another temptation to insinuate that his work excuses the injustices of his era or ours.4 It’s easier to venerate Claver’s work and leave it at that.

Yet promoting his charitable actions while ignoring his (or the larger Church’s) inaction in ending the institution of slavery can condone such silence. By extension, it can encourage a similar silence in us. But silence in the face of systemic evil is the same as consent, no matter how much good we may do. Unfortunately, many popular versions of St. Peter Claver’s life can make it seem that praising good deeds in our saints, our Church, or ourselves is enough for moving forward. It’s not.

Was St. Peter Claver morally right for what he did or didn’t do? The debate continues. But right now perhaps the more pressing issue is how do we face and use his legacy today. Making him into something he wasn’t, or focusing only on one aspect of his life over another, confuses the truth and is troubling enough. But what would be worse is if we allow such narratives to unjustly excuse us from our call to work for justice today. This would not only disrespect the actual good work Claver did but is also a roadblock to much-needed progress and reconciliation.5

- One incorrect interpretation of the Church’s Just War Theory argued that Africans, particularly non-Christian ones, captured in morally just combat could legally be enslaved ↩

- Or “the curse upon Canaan” (Ham’s son) is taken from the Biblical story of Noah cursing his son Ham’s descendents with servitude to his other two sons, see Genesis 9:20-27. Though the text didn’t mention skin color, the text was at times used to explain that Ham was a common ancestor of Black Africans and that darker skin was a continual marking by God to indicate that their enslavement was part of, or at least condoned by, Divine Will. ↩

- As cited by Father Samuel Knox Wilson SJ in American History (Chicago, 1929) ↩

- By the mid-1700s, the Society of Jesus in South America was a leading continental economic power, owning over 17,000 enslaved people. This figure includes Portuguese and Spanish America and was a factor for their eventual expulsion from South America. See Dauril Alden, The Making of an Enterprise: The Society of Jesus in Portugal, Its Empire, and Beyond, 1540-1750 (Stanford, 1996), 524. ↩

- Many thanks to William Chamberlin’s, “Baptized in Bondage: The Jesuit Ministry to Slaves in Colonial Cartagena and its Uses” which gave me a tremendous head start for this article. ↩