By the end of the 1960s, most of Africa was finally under native heads of state. People of African descent around the world celebrated, reinvigorated by a new sense of self-love and solidarity. This culminating sentiment of “Pan-Africanism” was expressed in many forms, like when Muhammad Ali and George Foreman returned “home” to the DRC (known then as “Zaire”) for 1974’s Rumble in the Jungle. But already by that time, national dreams of a successful future were eroding; today, very little seems to remain of that seemingly bright future. Instead, there’s continuing violence and under-development from an array of seemingly intractable problems. It raises the question, for this large state (and many others in Africa), why are such tragedies in the DRC still making headlines 57 years after independence, or more simply, what went wrong?

The “Dark Continent” to the Belgian Congo

There were different motives for Africa’s colonization in the 1880s. Some sought exploration and adventure while others hoped to save the people of this “dark” continent.1.] Ultimately, despite various proclaimed causes, the effect of Europe’s latest thrust into Africa became clear: African resources were to be extracted by any means necessary for European industry and wealth.

Like all colonial powers, Belgium was able to gain large territories (the DRC is about 77 times Belgium’s size) through “divide and rule” which exploited relationships among local people and placed Europeans at the top. As chronicled in the best-seller, King Leopold’s Ghost, the ensuing Belgian rule was brutal, unchecked, and saw the deaths of approximately 10 million; many others were intentionally maimed to maintain rubber quotas for export to meet global demand. As a result, even other colonial powers, educated by missionary and human rights’ groups’ reports of torture, genocide, and rape, forced the Belgian state to take control of the colony from the King who had been ruling it as his private property. Ultimately though, it was shifts in demand for rubber over the following decades rather than altruism that eased the conditions of de facto slavery for the Congolese.

An Unclear Independence

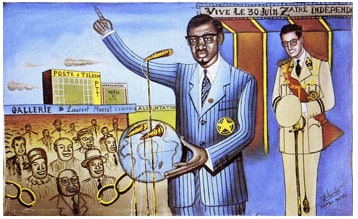

Independence finally came on June 30, 1960 under Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba. Freedom though would be complicated as Belgians remained heads of many industries and fields. The Belgian head of the Force Publique infamously explained the situation to his Congolese troops and police bluntly: “before independence = after independence.”

Congo also had the misfortune of being born during the Cold War and its rich reserves of uranium (among many other resources) were a prize for the US’ or USSR’s nuclear weapons’ programs. In fact, uranium from the Belgian Congo was used in the atomic bombs dropped on Japan. It didn’t help either that during Lumumba’s independence speech, rather than kowtow to the Belgian King and thank him for Belgium’s “civilizing mission,” he instead memorialized those who died under Belgium’s brutal rule. The King, who was in attendance, was deeply embarrassed. Lumumba’s speech pushed Belgium further away from a clear recognition of Congo’s independence and it continued working on a new version of “divide and rule” where resource-rich, pro-Belgian regions within Congo would be supported in seceding and/or overthrowing Lumumba – an early exercise in neo-colonialism.

When the UN refused to use its peacekeeping forces in-country to protect the increasingly fragile government, Lumumba was forced to request Soviet aid (a few years later, Che Guevara and Cuban military advisors spent time in the country). Lumumba was branded a communist and the next year, with the help of the CIA under orders from President Eisenhower, the Belgian government carried out the removal of Lumumba from power and had him secretly murdered, his body dismembered, and his remains scattered.

Le Grand Kallé’s Congolese Rumba hit “Indépendance Cha Cha”, sung in Lingala and French, was the theme song for Congolese independence and for African independence as a whole.

Congo Today and the “Resource Curse”

Why do rich states like the DRC so often fail? A common answer is the resource curse – that richly endowed countries like the DRC are manipulated, internally and externally, for their valuable resources, leaving them under-developed and susceptible to conflict. Fighting over resources like coltan – Congo has 80% of the world’s supply – is at the roots of the current fighting (which includes the recent “Africa’s World War” which cost 5 million lives). Not only is coltan essential for phones and computers, but also for video game consoles. Since demand for newly released technology has repeatedly correlated with a greater intensity of fighting, Congo’s violence has sometimes been called The Playstation War.

Though international players contribute to the situation for financial gain, this could not be possible without the collusion of elements within the country’s government that have been accused of corruption and greed. It’s been government forces that carry out much of the violence on the ground, likely including the kidnapping and brutal murder last month of two aid workers, as well as the exponentially more deadly humanitarian crises that have followed. Add to this various rebel groups who want a piece of the action. With such stakeholders benefiting from the chaos, it’s easy to see why there is so little effort to make concrete, positive change.

***

How do we fit in?

Because we’ve been living in a globalized world for a long time, our actions often have far-reaching consequences, so here are some things to consider doing as we think of our part in the DRC’s story:

- Reflecting on our consumption. The hardest, but most critical step. Since demand for the latest gadgets fuels destruction in the DRC, it’s important to consider what is and isn’t important to buy.

- Educate ourselves from a wider range of reputable sources like All Africa and Africa is a Country; avoid those that can give incomplete versions of what’s happening in Africa and why.

- Advocate to our governments to remove policies that subsidize (through our taxes for defense spending) our out-of-control arms industry. America is by far the world leader in weapon sales and our ballooning (under both parties) military budget sustains this industry which means direct and indirect supplying of weapons for conflicts abroad like the DRC’s. This is why, for the month of June, Pope Francis has called on us to pray for national leaders to put an end to the arms’ trade, which he called an “absurd contradiction”.

Confronted with harsh realities like these, it can be tempting to turn a blind eye and retreat into our own spheres to handle our own problems, which at times is as it should be; we have very real problems here at home too. The other temptation is an ultra-mea culpa mindset where we feel that all the problems of the developing world are our fault. But a view, individually well-discerned, somewhere in between, is best to determine our parts in the solutions.

***

Image courtesy FlickrCC user vfutscher.

- Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness (re-done in a Vietnamese context in “Apocalypse Now”), set in the Congo, plays on the theme of “darkness.” Conrad reveals its presence in European capitalism and imperialism, whereas it was commonly held to be only on the “Dark Continent” [Africa ↩