When Jorge Mario Bergoglio was elected the first Jesuit pope in 2013, there was a sense of corporate pride in our Society of Jesus. A Catholic wag quipped, “If you want to get a job done, call the Jesuits!” We had ample reason to rejoice.

Isaiah rejoices, too, in the first reading from Gaudete (“Rejoice”) Sunday:

The desert and the parched land will exult;

the steppe will rejoice and bloom.

They will bloom with abundant flowers,

and rejoice with joyful song.

The glory of Lebanon will be given to them,

the splendor of Carmel and Sharon;

they will see the glory of the LORD,

the splendor of our God.

Each time I hear these words, my mind returns to the sprawling Beqaa Valley of Lebanon, the fertile mountain plain that separates the Mediterranean sea from Syria. French Jesuit missionaries established a vineyard here in 1857, down the road from their sprawling mission-farm called the Convent of Taanayel, an Arabic word meaning “Spirit of God.” At 3,300 feet, the Beqaa valley enjoys dry summers and a water table fed by the melting snow of the Lebanon mountain range to the west, and the Anti-Lebanon mountains to the east.

The Jesuits had discovered there a series of underground caves which are still used to age wine. When French soldiers came to Lebanon after World War I, the French Jesuits introduced dry French red vines to the vineyards, which became wildly popular.1 The priests and brothers worked the vineyard in the Beqaa valley for 116 years, as wars came and went. Its fruit subsidized their missionary work throughout the Near East until 1973, when it was privatized as Château Ksara.2 Today, Château Ksara is the oldest, largest and most visited vineyard in all of Lebanon.

The Jesuits had discovered there a series of underground caves which are still used to age wine. When French soldiers came to Lebanon after World War I, the French Jesuits introduced dry French red vines to the vineyards, which became wildly popular.1 The priests and brothers worked the vineyard in the Beqaa valley for 116 years, as wars came and went. Its fruit subsidized their missionary work throughout the Near East until 1973, when it was privatized as Château Ksara.2 Today, Château Ksara is the oldest, largest and most visited vineyard in all of Lebanon.

If you want to get a job done, call the Jesuits.

* * *

But there’s another story in the Beqaa valley. Just a few kilometers from these beautiful vineyards, you’ll find sprawling refugee camps full of displaced Syrians, living in rows of tarp tents. At the center of each of these camps is a modest school compound, which runs morning and afternoon sessions for the thousands of children displaced because of the war. In response to the six-years-long Syrian crisis, these schools were established by NGOs that soon found the project too unwieldy. That’s when they called up the educational arm of Jesuit Refugee Service, the international non-profit which provides housing, food, medicine and education — as well as psychological and spiritual accompaniment — for 900,000+ people in over 50 countries every year. When other organizations have to pull out, JRS steps in to serve.

If you want to get a job done, call the Jesuits!

* * *

Fr. Boom Martinez SJ has led educational outreach with JRS for the past few years. Fr. Boom invited A.J. Rizzo, SJ and me to help train dozens of teachers in Beirut and the Beqaa valley earlier this year. Some teachers were Lebanese, others Syrian. Some spoke French; a few knew English. All spoke Arabic — except the three American Jesuits! With translators, we worked intensively for two weeks, helping prepare JRS school teachers – many of whom were young refugees themselves — to work with Syrian kids. After intense days of planning curricula and practicing classroom management, we visited the schools where the teachers worked.

It was on these visits to the camps that my heart ached with pain — but also soared with hope.

View from the schoolyard of a refugee camp, with Syria in the distance.

The tents were surrounded by open sewers and garbage. The curious faces of world-weary parents peeked out of tent flaps, as our vehicle passed through the dusty roads. When we got out of our vehicle, children yelling to each other in Arabic came running up to us, smiling their toothy grins, eager to see these strange faces. Isaiah writes,

Strengthen the hands that are feeble,

Make firm the knees that are weak,

say to those whose hearts are frightened:

Be strong, fear not!

Here is your God,

he comes with vindication;

with divine recompense

he comes to save you.

What did we three Jesuits, training a few teachers, hope to accomplish for these kids? What hope could we offer a world marked by prolonged violence? Not much, I feared.

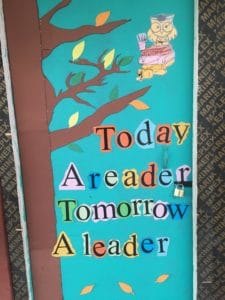

But at one of the schools a simple sign in bright colors gives children renewed hope:

And at another camp’s school, a large word cloud greets students each day: You are a mathematician. You are an explorer. You are the future. You are respected. You are loved.

Those whom the LORD has ransomed will return

and enter Zion singing,

crowned with everlasting joy;

they will meet with joy and gladness,

sorrow and mourning will flee.

This time it wasn’t Jesuits doing the heavy lifting. But we did get a first-hand look at the heroic love of selfless teachers – many refugees themselves — who clearly wanted to provide hope for their students’ futures. These teachers are Muslim and Christian, old and young alike. One older Muslim principal, Amena, was a college chemistry professor in Syria before the war. Now she runs a school in a refugee camp. But she smiles infectiously, adores her teachers and students, and runs her school on a shoe-string budget.

* * *

I marvel that it was not far from here – just a few hours’ drive south of the Beqaa valley — that Jesus Christ, born in a stable, became fully human. In an auspicious moment, God chose to enter fully the fray of humanity. This scorching-by-day, freezing-by-night corner of the world has seen the steady march of wars, religious strife, and displaced peoples for over 4,000 years.

We might take a minute to let this fact unsettle us — it was to this messy place that God sends his Son. Not to palaces of power, or to the quiet of ornate sanctuaries. In the Gospel of Matthew, Jesus challenges the crowds’ expectations of John the Baptist, who would announce the Messiah:

“What did you go out to the desert to see?

A reed swayed by the wind?

Then what did you go out to see?

Someone dressed in fine clothing?

Those who wear fine clothing are in royal palaces.”

The Jesuit missionaries in the Beqaa have long ago given up running Château Ksara — though bottles of Réserve du Couvent honor the history. Today they continue their work at the nearby Taanayel farm and retreat house. Jesuits have stayed there, despite wars raging around them, since they first arrived. The mission building has been raided before, and heroic Jesuits have been martyred there as recently as 1985. They minister to refugees, offer retreats and conferences for JRS workers, and employ dozens of locals who make dairy products like labné.3 The mission serves as a place of rest for Jesuits who work in Aleppo, Damascus, and other distressed places in Syria. Their work as Christian missionaries is not glamorous — but that is not what they signed up for.

* * *

In this bittersweet corner of the world, refugees camp next to vineyards that produce some of the finest wines in the world. And yet refugee kids go on being, well, kids — running and chirping, making mud pies, playing basketball as the sun sets over the landmine-scarred mountains near Syria.

They learn a little bit in school: You are a mathematician. You are an explorer. You are the future. You are respected. With the help of JRS, we dare hope that they learn, deep in their bones, that they are above all beloved children of God.

* * *

Ours can be a cosmically tragic world. It can be difficult to rejoice when we learn of suffering — our only option seems to be to turn away, as a way of protecting our hearts. Yet it is precisely to this beautiful corner of the world that our God saw fit to break in, to interrupt human activity. This God-with-us, Jesus, teaches us that pleasure is shallow, but joy — true Christian joy — makes room for pain at its center. And thus,

The desert and the parched land will exult;

the steppe will rejoice and bloom.

They will bloom with abundant flowers,

and rejoice with joyful song.

The glory of Lebanon will be given to them,

they will see the glory of the LORD,

the splendor of our God.

For that, we can certainly rejoice. Because when the task is to redeem the world, don’t send a Jesuit. For that, only the Son of God will do.

Consider making a donation this Christmas to the good work of Jesuit Refugee Service.

–//–

All photos were taken by the author.