This is the second installment of two in which Bill McCormick, our resident political scientists, asks us to consider the delicate dance of faith and politics.

Last week I asked whether one can be Catholic and Republican. Readers had a variety of responses, of course. But I was most struck by how obvious the answer was for many, one way or the other. So often in history something has seemed obvious, only to become… not so obvious.

Until the past few decades, for instance, it was obvious that to be Catholic was to be Democrat, especially for ethnic whites. The Catholic Church and the Democratic party were the most welcoming institutions to vast numbers of Central, Southern and Eastern Europeans arriving on U.S. shores. The Church and the Democratic party offered cradle-to-grave services, local community support, and a sense of the familiar in a strange place. They were a source of identity and protection from the wider world, but also a means to integrate with that world.

And integrate they did. Consider John F. Kennedy, Jr. The Boston-Irish JFK was undeniably an embodiment of this Catholic-Democrat culture. But he also transcended it. The son of a people long-despised on these shores, he rose to the highest office in the land, representing the American success story that the Irish had become.

But perhaps it was a Pyrrhic victory — the white ethnic Catholic Democrat had “made it,” but was no longer quite so distinctively Catholic or Democrat. Given this, we should not be surprised, as Sean Michael Winters notes, that the days are over when the Democratic party could count on the monolithic Catholic vote. Indeed, there is no one “Catholic vote.”1 This would explain the story of Mike Pence, a politician who left his Irish Democratic Catholicism behind to become an American Republican Evangelical. Pence is now the GOP nominee for vice president.

All of this to say: if you think something is “obvious,” just wait twenty years and it won’t be. Similarly, while for many readers it’s simply obvious that one can be Democrat and Catholic, recent American history suggests otherwise.

To put a finer point to our question: is the Catholic Church and Democratic party moving back together, or continuing to part ways?

A number of readers asked me last week to be more specific, to offer more examples of how faith intersects with politics. As we know, offering examples isn’t always helpful in political conversations, because I’ll have my interpretation of it and you’ll have yours. In other words, we risk missing the original issue as our interpretations become mutually incompatible.

But one has to start somewhere.

The example I’ll take is the perfect case study of the ways in which the Democratic platform and the Catholic Church have parted ways: pro-life politics.

Life issues are always complicated for Democrats, as the party as a whole seems to get most of the “pro-life” message except for the crucial issue of abortion. What does it mean to be “pro-life,” anyway? As the U.S. bishops point out, “Both opposing evil and doing good are essential.” At the very least, then, being “pro-life” means opposing things that lead to death, which is a problem for the aggressively pro-abortion platform of the Democratic party. When people point out pro-life Democrats, they tend to refer to politicians like Bob Casey, Jr., who seem to have little influence in the party about the contested issue.

In terms of promoting life, the Democrats aim to be the party of women and children, immigrants and minorities. The general air of inclusion and tolerance espoused by the Democrats is an important form of being pro-life: standing up for lives that are often taken not to matter.

And that is why I — and many young Catholics — simply do not understand the Democratic platform on abortion. Why protect everyone except the most defenseless? Democrats have championed “black lives matter,” and I am sure they would add that gay lives matter, immigrant lives matter, female lives matter, poor lives matter, Latino lives matter, and so on. But what about unborn lives?

Catholic Democrats will often claim that Catholics can’t impose their religion on other citizens, as though somehow only Catholics possess the knowledge that taking innocent life is wrong. But if that were the case, why, then, do the very same politicians impose their “religious” beliefs on others by opposing the death penalty, or welcoming the immigrant, or supporting religious and racial minorities? Those are also calls of the Gospel, after all. And that was Pope Francis’ message when he spoke to Congress last fall: “The Golden Rule also reminds us of our responsibility to protect and defend human life at every stage of its development.”

Catholics in the Democratic party have an opportunity to proclaim that dignity and respect are due every person, but instead we have become used to making excuses for why the party has only become more pro-abortion. This is the situation we find ourselves with Tim Kaine, Hillary Clinton’s pick for vice president. The man has so many wonderful things going for him, and would easily be the best-formed Catholic of any VP or president in our nation’s history. So how is it that Mike Pence, the man who left the Catholic Church, is the more pro-life of the two VP candidates on this issue?

* * *

My fear is that too many Catholics are afraid to draw the connections between their faith and justice. For most of American history, Catholics have been accused of being beholden to a foreign power – the Pope in Rome – and being unworthy of citizenship. With Kennedy, we had to prove that we were “real” Americans. Is that what is happening, in its own way, now? Are we giving in to such fears? Are Catholics afraid to let their faith serve and promote justice because they think that Catholics can only get elected if they promise not to be too Catholic?

What did the election of JFK really accomplish if we are still – in 2016 – afraid to be Catholic in the public square?

And even if we agreed that Catholic teaching on the taking of innocent life had to be excluded from the public square, could Catholics nevertheless be in dialogue with abortion advocates? The Democratic justification for abortion — that women have a right to choose what to do with their bodies — is based upon an important half-truth. For the truth in the “half-truth” is that the language of “choice” can beautifully and powerfully affirm the dignity and rights of each human being — not least of all women, who have been victims of much violence for millennia. The dignity of the human person is in fact a cornerstone of Catholic Social Teaching.

But this truth can only be a “half-truth” when that dignity and those rights are seen to confer on a person the power of life and death over another. The way to rectify the oppression of one group cannot be to give them the power to silence another one. That is not justice. Catholics cherish the common good, and the common good demands the protection of both women and children.

So here is my question: how can our faith challenge American “choice” to expand to include not merely my own wellbeing, but the wellbeing of the other? Can we come to see that a person’s choice should never lead to the harm of those less vulnerable?

That is the Catholic challenge to the Democrats, and by that I mean that every Catholic Democrat should do what she can to change the Democratic platform on abortion. And that includes Catholic men! If Catholic men do not show respect to women through their thoughts, actions and words, then those men do not deserve and will not gain any credibility on the subject of abortion.

* * *

Now, let us be perfectly clear: the GOP has its failings when it comes to pro-life issues, as well. The GOP has always been in favor of the death penalty, for instance, and many in the party turn a deaf ear to the plight of immigrants, women and minorities. The legacy of Vietnam has also rendered the GOP more hawkish than the Democrats. 2 The GOP, in other words, is good about saying “no” to death in its push against abortion, but not good about saying “yes” to life when it comes to a constellation of policies that are deeply connected to the sanctity of life. They could take a lesson from John Paul II in Veritatis splendor:

[T]he fact that only the negative commandments oblige always and under all circumstances does not mean that in the moral life, prohibitions are more important than the obligation to do good indicated by the positive commandments (§51, italics added).

The pope goes on to say that “the commandment of love of God and neighbour does not have in its dynamic any higher limit, but it does have a lower limit…” Indeed, it frustrates many that some U.S. bishops seem to side with the GOP in emphasizing the “no” to death more than the “yes” to life. Still, it is hard to call the GOP less pro-life when the Democrats continues to become more and more pro-abortion.

* * *

If you think I am being harsh on the Democrats, you are absolutely right. Because it frustrates this Catholic endlessly that the DNC is so close — and yet so far! — to the Church on this issue.

And this “so close and yet so far” quality is worth reflecting upon. For one can make plausible claims that one party is more pro-life than the other. But the more important take-away is that neither party is fully committed to a Catholic concern for protecting life. They both have their little enclave of pro-life issues that they get right, but without seeing the connections to other issues. Neither party, in other words, has treated the garment of life as “seamless,” to use Cardinal Bernardin’s phrase. Both parties have issues clearly aligned with Catholic Social Teaching, but fail to see the connections to other issues.

The challenge for Catholic citizens is to sift among morally flawed options. But what happens when citizens are regularly forced to choose between two evils? I suspect the temptation then would be to treat the lesser evil as good by default, i.e., my candidate is good because the other candidate is bad. Yes, Democrats and Republicans can have good reasons for choosing one party over the other. But if you stop seeing the limitations of your party, then you stop seeing the need to maintain a critical distance from the sources of those limitations. Add in polarization and a climate that encourages us to think that everyone who disagrees with us is simply wrong, and you get a political ideology far more dogmatic than any religion. You get an ideology, in fact, that refuses to be judged by a higher standard.

* * *

To state the obvious: no Catholic voter can expect either party to properly form her conscience. That’s why I mentioned the need for Catholics to dive more deeply into Catholic Social Teaching, found for example in the Compendium. I suspect part of why so few Catholics know this wonderful literature is because so few understand why the Church — and lay Catholics especially — ought to weigh in on issues relevant to public policy. Again, the conference of Catholic bishops suggests that:

The Church’s obligation to participate in shaping the moral character of society is a requirement of our faith, a part of the mission given to us by Jesus Christ. As people of both faith and reason, Catholics are called to bring truth to political life and to practice Christ’s commandment to “love one another” (Jn 13:34).

A politics based upon love for every person as our neighbor — especially those we disagree with — is not going to arise through the efforts of our political parties. It is up to Catholics and people of good will to do the careful reflection that our country, and the world, need today.

–//–

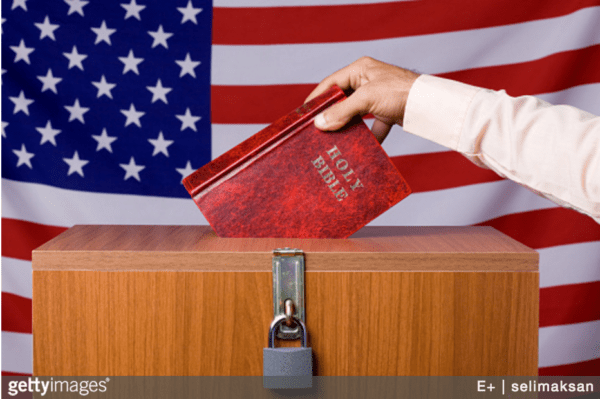

Embedded images by Getty Image users Keystone-France and Selimaksen, follow fair usage policies of Getty Images.

- There is good reason to think that there are a few “Catholic votes,” divided by race and ethnicity. See http://www.pewforum.org/2016/07/13/evangelicals-rally-to-trump-religious-nones-back-clinton/pf_2016-07-13_religionpolitics-00-02/. ↩

- Although Hillary Clinton seems more hawkish than Trump, a subject for a different essay! ↩