It’s been a volatile market for NFL quarterbacks this spring — at least for the B-list ones.

Brock Osweiler was the heir apparent to Peyton Manning, until he took Houston’s $72 million instead. The Browns cut Johnny Manziel, volatile in his own right, then replaced him with Robert Griffin III. But this QB shuffle has one man thinking he has a leg up on the opposition: celibacy.

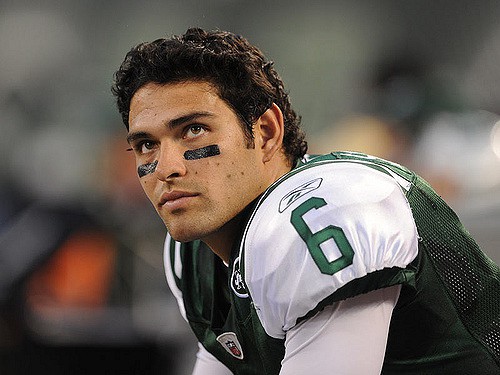

“I’m not married. I don’t have a girlfriend. I don’t have kids,” said Mark Sanchez, in his first press conference as a Denver Bronco. “I just want to play ball and I want to win.”

I always thought celibacy was weird, but maybe it’s catching on…

Sanchez’ new ethos reminds me of the way I often explain celibacy: appeal to pragmatism. Priests and religious, both men and women, aim to be available to so many people — the hundreds of students in a school, the thousands of young people on a college campus, or the many families that form a parish. They cannot possibly be present to all these people, the argument goes, if they are also committed to a spouse and kids. So they take a vow of celibate chastity.

Maybe it works in football too. Sanchez, I guess, is responsible for keeping thousands of football fans happy. His new team just won the Super Bowl, so expectations are high. He’s filling the shoes of a legend, and that didn’t go so well for him last time.1 So he’s disavowed the distractions of a family to be fully present to football. And if you take him at his word, he is fully present to football:

“Every waking moment, that’s all I’m thinking about, is what an opportunity this is, and that I want to win and I want to play here,” Sanchez said.

If only my celibacy gave me such laser focus on serving the people of God!

The thing is, celibacy is supposed to be more than pragmatic. (And, one hopes, a spouse and kids amount to more than mere distractions.)

The practical side of celibacy is important and meaningful. I began learning that before I joined the Jesuits, when I taught English at De Smet Jesuit High School. For nine months, my whole life revolved around my sophomores. For the first time in my life, I was totally others-centered. My success was my students’ success. It was a hard but beautiful year. It made me want to be a Jesuit.

But pragmatism alone can’t justify celibacy. Married clergy, Christian and otherwise, also lovingly and effectively draw their congregations closer to God. And the practical argument tries to make celibacy seem normal or rational, when — let’s be honest — it’s not.2

So why do something abnormal? Why take a lifetime pass on sex, which is such a fundamental human experience? Well, celibacy aims to remind us that sex — fundamental or not — is not everything. Celibacy points beyond human pleasure to something even greater: the Kingdom of God.

Let’s be clear: Celibacy is not anti-pleasure. For married people — who far outnumber celibate people — sex is supposed to feel good! It should even draw people closer to God. But regardless of our vocations, we are meant for more than human pleasure. God wants us to enjoy eternal bliss with him in heaven. Celibates try to remind us of that reality, which is why they’re sometimes called “eunuchs for the sake of the kingdom.”

I am eager to see how Sanchez’ celibacy experiment goes. I hope it works! It might help me explain my own celibacy to others.3 But ultimately, celibate or not, we’ve got to aim for something greater than the endzone, bigger than the Super Bowl, and even better than sex. We’ve got to aim for God.

-//-

Cover image courtesy Flickr Creative Commons, available here.

- Check out these QB rankings from his rookie year, when he succeeded Brett Favre on the New York Jets. ↩

- As my wise novice director said, celibacy is supposed to be weird! ↩

- And I’m a Broncos fan… ↩