I visited the Equator a few years ago outside of Quito, Ecuador. It was pretty much what I expected, countless giggling people taking pictures of themselves straddling a painted line, surrounded by gaudy tourist attractions. I think I had a beer to celebrate. Seen it.

This spring I went to visit another line I had only seen before on maps. But beside this line there were no tourist traps, even fewer tourists and no giggling line-straddling pictures.

*

The US-Mexico border, devoid of cutesy frills, is hard to miss. Any section within 10 miles of anywhere remotely ‘urban’, we’ve traced the map’s crooked lines with a 20-foot tall steel fence, a red-brown color somewhere between desert, blood and rust.

Nogales is a city cut into two parts, one Arizonan, one Sonoran. I visited both in March during a spring break immersion trip — one of those trips where you go to grind your heart and mind up against hard places, while meeting the people that live there full-time.

*

I met Victor at a shelter on the Sonoran half of Nogales on a Sunday night. Waiting for the dinner bell in a spacious room, he leaned up against a table and told me he was from El Salvador. We talked about his children, we talked about his wife; we talked about the God who kept him company when he was far from them, sending home precious little each month, a pilgrim for labor.

We spoke in Spanish. Twenty minutes later I met his brother, Carlos, and as Victor began talking to one of my non-Spanish-speaking trip-mates, I realized that he was fluent in English. He had been living in the United States for the past decade. He was deported; he was simply trying to return; he was accompanying his brother on Carlos’ first attempt to cross. Together, they decided they would make the trip. For the sake of the families. Together, they said goodbye — first to their children, then to their wives. They carried with them their tattered backpacks, gallons of self-doubt and desperation tossed in with family photos and rosaries, amulets of hope.

The dinner bell rang, and we all said goodbye. I crossed the border and went to bed.

*

I have limits. But crossing the US-Mexico border is not one of them. Finding employment for adequate housing, adequate nourishment and adequate safety in my home country is not one of them: I am privileged.

*

The next morning, we met again at a “Comedor” where we, the volunteers, poured juice while rain pounded the corrugated tin roof and wind slapped the canvas walls. Waiting for the van that would take them back to the shelter, Victor saw me and said suddenly, “I’m too old. The desert is too much. I can’t do it.” His eyes were cloudy, his body slumped, his voice defeated. His brother Carlos was sharply dressed in a US Men’s Soccer zip-up, sporting trim black hair, smiling with a young face, bright eyes and the visible eagerness of a first-timer.

Later that week, Carlos will march in a northbound single-file line of a dozen men, women, and children carrying gallons of water under a blazing sun, trekking through burning days and freezing nights and all the blisters in-between. It’s fourteen days, if he makes it, to Tucson.

The van pulled up. Victor, Carlos and I said goodbye, our last one. I crossed the border for dinner and group reflection.

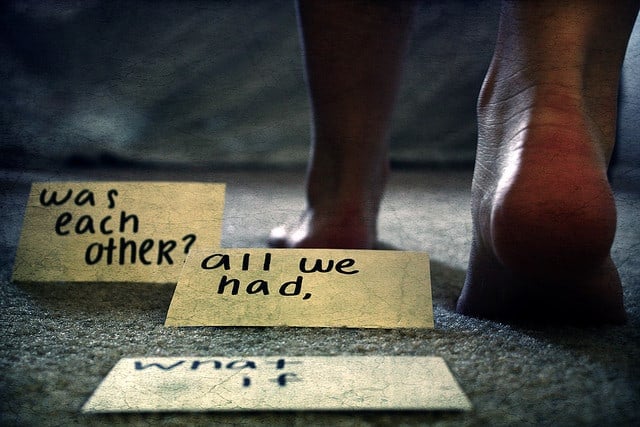

Together, they had weighed every risk — economic scarcity vs. opportunity; their children’s hunger vs. the risk of their desert passage; their familiar life in Salvador vs. the racism, discrimination and dangers of undocumented life in America. Together, they weighed the risks and found them worth the hope. Together, they said goodbye. Together, they trusted all they had: each other and the small voice of hope. That night, my stomach turned, and I stared at the ceiling, not sleeping.

The wall makes a visual impression that sticks. It sticks and doesn’t play nice with other thoughts. I cannot wrap my head around this. I cannot wrap my heart around this. I cannot imagine Victor breaking the news: “Brother, we’ve said goodbye to everyone already, but now I can go no further. Can you bear another goodbye?”

*

I have limits. Crossing the border is not one of them. My wall, instead, is where my idealism ends, where it, at full-sprint smacks, breaking itself. I feel powerless up against steel reality. This steel wall divides countries, families, and severs hope in two. It represents bipartisan gridlock and a seemingly perpetual inability for government to recognize and meet the needs of the most vulnerable. I ran up against it both then and now, broken with despair, overwhelmed.

I cross every other border at will. This one halts me. Every do-gooder term I tout loses its legs — justice, accompaniment, transformation, healing, political conversion, advocacy, praxis, solidarity — they all wobble on stilts, knocking into one another and toppling over. The curtains are drawn too early and they’re exposed for the pedantic idealisms that they are. Great on paper, not in person. The wall wins. It crushes and divides.

*

But there’s a small voice within me that suggests that these walls won’t win.

Dumbfounded and hopeful, I am drawn to listen. Victor and Carlos are driven by a gut-level force, a pulsing mass of faith, hope, and perseverance, alive in the remembered faces of family and visions of laughter and abundance. It’s their courage to go on; it’s their courage to return home. It speaks from their heart to their own steely willpower. It’s not perfect, it’s not blameless, but it’s their response to despair, to family divisions, to deserts and to dead-ends.

The voice is small. But it’s the voice of Victor and Carlos, the voice of their pilgrimage, their walking witness of courage, hope and love. Often ignored, this voice deserves to be heard for its own sake. And, in my own fear and limits, I desperately need to hear it.

–//–

The cover photo, by Flickr user Wonderlane can be found here.