thierry ehrmann / flickr creative commons

The most afraid I’ve ever been was in a movie theater.

A theater a few blocks from my house regularly has midnight “cult classics” showings. Imagine films like Pulp Fiction and Back to the Future shown with fans coming out of the woodwork dressed in complete character. As you sit down with your popcorn and pop 1, you could very easily find yourself sitting next to Marty McFly, complete with red down vest, who quotes every line to his own movie.

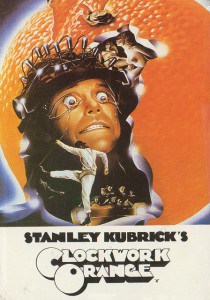

One evening, the theater showed A Clockwork Orange. As people started to line up, I found quite a few dressed in suits with bowler hats addressing each other as drüg (Russian for “friend”) and other Russian terms found in the film. Many people had outlined their eyes with a sunburst in imitation of the main character of the film, Alex DeLarge.

The film presents a grim reality, and Stanley Kubrick intends to use the movie as a mirror so the audience might reflect on how we live outside of the film. As a focal point for this reflection, he seems to ask, “How ought we respond to violence?”

One sequence from the evening surfaced this question. In the course of the movie, Alex DeLarge and his gang raid a home. Kubrick shoots these scenes using a quirky, almost comical style: short, clipped shots with DeLarge dancing and singing to “Singing in the Rain” as he executes his path of destruction.

At one point in this sequence, DeLarge commits a rape. The rape has the same music, dancing and almost giggly feel as the rest of the raid. While I found myself very disturbed at this scene, something frightened me even more than this act of brutality; almost the entire theater was laughing during the rape scene.

The laughter arrested my thinking, and my heart rate increased as I looked around to find many DeLarge look-alikes laughing at the real (that is, fictional) DeLarge’s actions on screen. Certainly not everyone was laughing, but the sheer number of people in costume disallowed any distinguishing between who participated in the grotesque comedy and who did not.

As I sat in the theater, I wondered about something similar to what Kubrick asks us with his film: How ought I react to imposter DeLarges who flippantly laugh in the face of rape? Moreover, what does it say about me that I was present in the first place?

As an act of protest, either to the film or the reaction around me, I could have simply left the theater. This response would have satisfied my need in the moment to distance myself from the theater-goers who, in my estimation, did not show the appropriate response – namely, mine – to the events on the screen.

At the same time, I could have focused more on my own internal disposition, rather than external, symbolic actions. I could have first wondered if I were overreacting. This is just a movie, right? Is it justified for me to make the leap from how my fellow audience-members react to fiction to who they are as people?

Frankly, though, I didn’t do any of these things. Instead, I sat trembling in my seat for the rest of the show.

A few days after seeing the film, I was discussing my reactions to the experience with a few friends who had also attended the show. Most of my friends pointed out their visceral, gut reactions to the event taking place around them. One even shared a few choice words he had planned to have with people he saw laughing, but was unable to because his fury caused him to leave the theater as soon as he possibly could.

I mentioned how, either when personally witnessing violence or seeing it through another medium, I find myself in shock and fear. This viewing of A Clockwork Orange helped me see that these are good and even productive emotions to experience during such episodes, as they orient my focus toward an event that ought to remain outside the commonplace experience of any person’s life.

My friends noted how few others in the theater seemed to share that response. Our conversation eventually reached a lull, followed by the question that was on everyone’s mind: “Now what?” The question lingered, as none of us had a ready-made response. Sadly, no one found anything definitive to say. The experience shows that while denouncing violence often proves simple, creatively challenging it does not.

Image by Rev. Xanatos Bombasticos / Flickr Creative Commons

One of the options that did arise, however, was that of completely avoiding any movie that portrays violence. The reasoning was that, since films seek to earn a profit, any use of violence that assists such an aim only ingrains its acceptance into the film’s viewers. This response resembles my earlier one of walking out of the theater; it makes a strong symbolic statement, but does not necessarily look to the heart of the matter at hand.

Certainly not all films use violence the same way. Of late, more and more have used it for sheer entertainment value. For example, the upcoming release of the latest instalment of The Expendables portrays vigilante justice wrought by the hands of hyper-weaponized men. Good and evil still have easy demarcations, and the ensuing explosions and exchanges of gunfire and roundhouse kicks accomplish the triumph of good over evil. Good, clean entertainment.

What A Clockwork Orange does, however, is try to disorient the viewer. The happy-go-lucky music of “Singing in the Rain” represents what we expect from popular cinema, while the actions on screen portray that which we look to escape. Regardless of the audience’s reaction, the film accomplishes its aim; if it frightens the viewer, then she or he recognizes the potential problem with passive entertainment. If the viewer has no reaction or even responds with laughter, then the film reveals the same dilemma: that entertainment has helped numb people to the violence, though often hidden or disguised, that surrounds us.

So, using Kubrick’s film as an example, it seems that one response to such depictions of violence is to analyze closely the media that we consume. Media conveys stories, and the stories we hear and tell each other have a profound impact on what we choose to see, what we allow to move us and motivate us. Violence ought to throw us off center. Any other reaction befits the DeLarges, fictional and otherwise.

For another recent take on violence, you can check out Responding To Violence In A New Way.

- That’s right. Pop, not soda. ↩