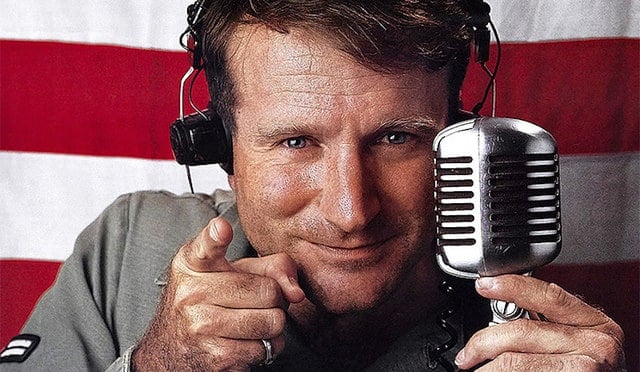

If there is any compliment worthy of Robin Williams’ career as an actor it might be that his death was a reminder of how familiar he felt to us. He portrayed characters we came to love with such authenticity that we began to believe we knew him well. I was saddened by news of his death, but not entirely surprised. Many of us struggle with addiction and depression and I could see a familiar sadness in him. In his performing you got the sense that he was trying very hard. His comedy rushed at the world like a firehose trying to douse the flames of pain. And we lined up to be doused. We threw ourselves again and again into his manic stream of laughter.

Many have puzzled, “But he was so successful; I just can’t understand.” Perhaps we ought to think more carefully about our notion of success. Perhaps it’s better to say that he was working really hard. He gave everything he had in the work of fighting back the fears, the pain, and the loneliness we all know more than we’d like to admit. As an actor, he gave himself to terrifying truths so that we might bring into the light feelings we’d rather keep in the dark. He did this work with his whole heart. He gave everything he could. In that sense, yes, he was successful. But let us not be surprised when the successful show themselves in sadness lest we trick ourselves into thinking that success can banish sadness without suffering it.

***

I had just arrived with five Jesuit companions to a condo by a small lake in the eastern Sierras. We had come with a mutual Jesuit friend who had lost both his older brother and his father in the previous months. We joined his mother and some family friends to lay his brother to rest in the place where, just a few months earlier, others had come to do the same for his dad. When word of Robin Williams’ death swept into our newsfeeds we, like millions more, sat in shock. Somehow the expressions of sorrow and surprise were more than status updates. They were all too familiar feelings.

The following day I sat beneath a bright morning moon that hung just over the ridge to the west. I saw her as I came onto the porch with my cup of coffee. Big rolling clouds began their morning commute across the mountains into the desert and obscured her soft luminescence. But she was there – my lunatic friend – just beyond the clouds. Meanwhile, a wall of granite peaks stood tall like a mirror glowing bright pink as their gray stone faces reflected the new light of the rising sun, yet unseen, behind me. The natural world gives itself to us equally in moments of joy and sorrow. We could stand to learn her lessons and to do the same for each other.

***

Clowning is a kind of prophecy and laughter a kind of surrender. Every king needs a fool, more for humility than entertainment. Nothing strips us of our royal garb and our sense of self-importance more efficiently than an honest laugh. Sincere laughter submits the body entirely to the laughable moment with the recklessness of a sneeze or an orgasm, a spontaneous convulsion of the senses–involuntary and exhilarating. In laughter as in lovemaking, religious ecstasy, and tragic loss we shake, we double over, we cry, we lose control. It is a gift and, like any good gift, sincere laughter is both free and spirited, and, in its own way, terrifying.

The truly great comic is very much aware of the tragic failures we all experience. The tricksters and fools we love so much accompany us in a way that makes annihilation feel more like exhilaration than oblivion. A good comic teaches us a profoundly important lesson–that our tears can be a sign of freedom, that fear and pain are somehow essential relatives of joy and gratitude. In a candid and somewhat tortured interview a journalist once asked Robin Williams if he was happy. He responded softly to the question, “I think so. And not afraid to be unhappy. That’s okay too. And then you can be like, all is good. And that is the thing, that is the gift.”

***

One morning we took a boat out onto the lake and prayed for and with the dead. We were a small group of friends and family, some of us strangers to each other, but all of us were held together in that small boat, suspended by the mysteries of buoyancy, held in the strange tension of weight and displacement. There was a soft wind from the west as we prayed under the warm sun and above the cold depths of the lake. When all was done we pulled away through the water, our tired eyes squinting at the brightness of a thousand suns in the reflection of morning light upon our wake.

What do we do in times like these? We sit. We bring food. We pray. We choose again to live. We spend everything in truth and authenticity. We give ourselves to joy because there is reason to rejoice. We give ourselves to sadness because sometimes there is reason for that too. But most of all, we give ourselves again to one another because the greatest tragedy of all is, in Robin Williams’ words, “not to be alone, but rather to be with people who make you feel lonely.”

We wake. We show up. We eat and drink. We companion each other. We try not to make each other feel lonely. Sometimes we lose control. Sometimes we cry. Sometimes we laugh.

–//–

The cover image, from Flickr user Phil Shirley, can be found here.