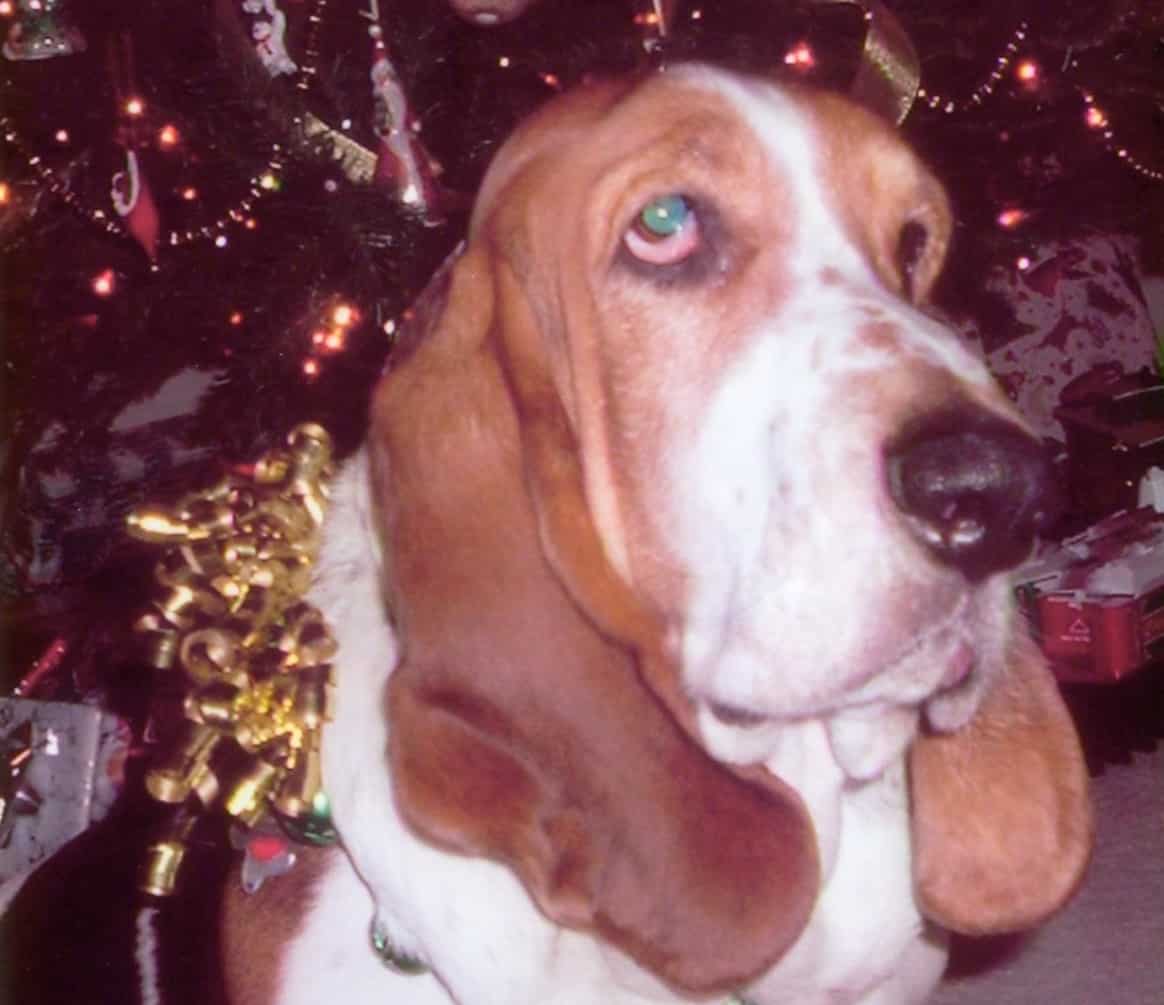

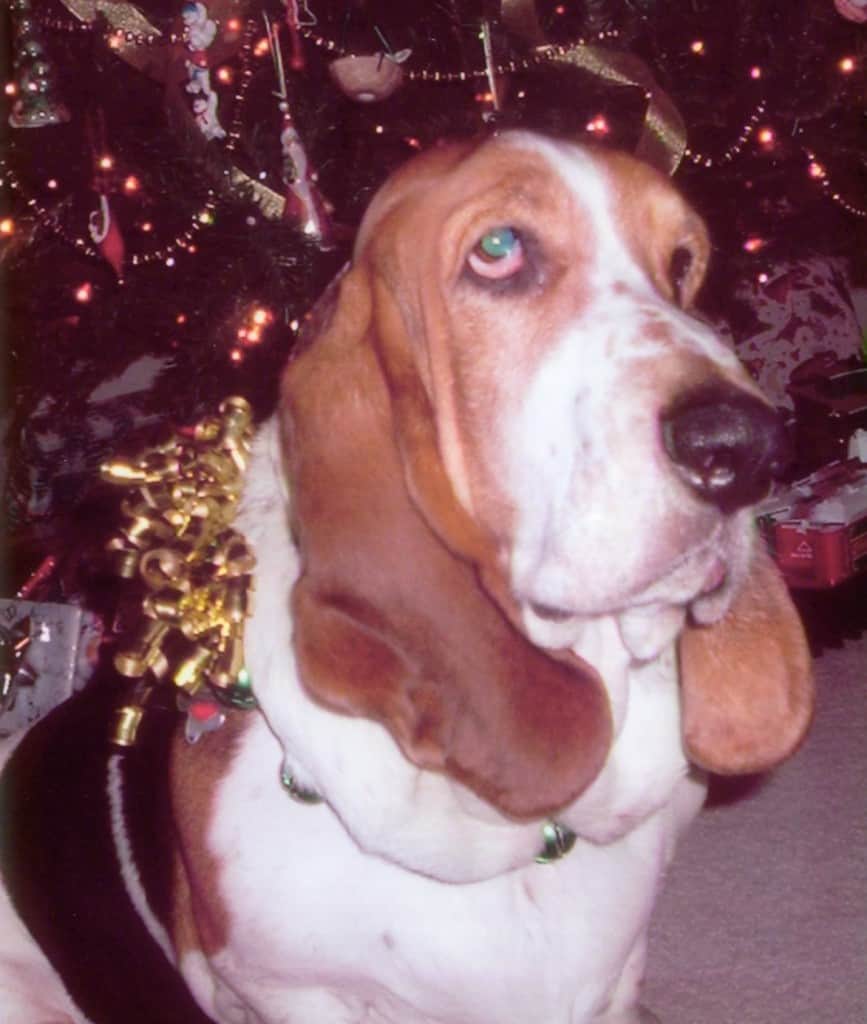

Tristan Xavier: deconstructing the naughty/nice binary

Tristan Xavier Stayer—the dumpiest, doofiest, dim-wittedest, and dearest basset hound that there ever was—passed away this week. Or, to be straightforward, I should say we killed him. My brother, sister-in-law, and I. Not in cold blood, of course. He was thirteen years old, and the slow drift of the past three years had become a rapid decline, and it seemed the only decent thing to do.

I had wanted a basset hound since fifth grade, when I met a friend’s basset. Growing up, my siblings and I had had a beloved beagle, so medium-sized hounds were built into my sense of what makes a home. But as an adult, I didn’t get my own dog until the age of thirty-three. Somewhere between middle school and middle age, the basset hound of my imagination had shrunk to the size of a beagle. This error was remedied the moment I stepped out of my car at the breeders’ home, and thirty basset hounds swarmed towards me, yowling like lost souls in hell. My childhood beagle had been about twenty-five pounds, whereas these low-lying tanks—lumbering, gigantic torpedo-beasts—were easily eighty pounds. Whoa, I thought, this is bigger and messier than I had bargained for. The sensible thing to do would have been to admit that maybe I wanted a long-eared beagle and to apologize to the breeders for wasting their time. But by this point in my life, it seemed dumb to turn back. So I picked one out. Large, slobbery dogs may not be to everyone’s taste, but there is nothing cuter than a basset hound puppy.

Part of the appeal of basset hounds is how comically they act and how ridiculous they look. And so the irony of giving him a dignified name was irresistible: Tristan for Wagner’s opera, Xavier for the Jesuit saint. I should clarify: I was not a Jesuit at the time I got Tristan. If I had had even a suspicion that I would join the order, I would never have saddled myself with a pet. I had Tristan for two years, and after I entered the Jesuits, for the next eleven years, he lived with my brother and his family, where I got to see him often during family visits. And he always recognized me, if only by smell in his nearly-blind stage: he would bark at me until I sat on the ground and scratched the spot under his neck that made him thump his hind legs, an expectation he never imposed on other visitors.

Another thing my idealized notion of bassets hadn’t accounted for was how unmanageable they are. I was used to the dogs of our family, who were generally obedient.1 But since bassets were initially bred to be tenacious, to follow a scent without being distracted, it means that their attention cannot be redirected easily. Breed manuals have a polite way of describing how hard they are to train: bassets comply, presumably, after a “characteristic delay.” Tristan’s own attitude to obedience was a mixture of laissez faire and noblesse oblige. He rarely did what was commanded when it was commanded. But he could not strictly be described as disobedient, because his casual disregard was not born of an anti-authoritarian impulse. Tristan seemed to ponder every command in an abstract way, as if he were considering its metaphysical import rather than its imperative claim. Thirty seconds later, he would disregard it as irrelevant to his person.

Congenitally stuck near the ground, Tristan had a preference for short people and children. His politics were a jovial libertarianism. And in spite of being raised by Catholics, his theological inclinations were Unitarian. Given the choice between eternal salvation and hamburger meat, he would have chosen the latter. He understood what was done and what was not done, but he was not plagued by a guilty conscience; he took scolding as a personal affront and firmly believed that it reflected not his wrongdoing but the scolder’s vulgarity.

Shakespeare noted the basset’s peculiar qualities in A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Hippolyta exclaims: “I never heard / So musical a discord, such sweet thunder”—an elegant description of the range of expressive noises that a basset makes. (If you have never experienced this booming pleasure, you’ll want to google “basset howling.”) Here’s a clip of Tristan singing.

Another Shakespeare character adds: “their heads are hung / With ears that sweep away the morning dew / Crook-knee’d and dew-lapt like Thessalian bulls / Slow in pursuit, but matcht in mouth like bells.” It is likely that Shakespeare admired from afar the musical howl and long ears of the basset. If he had owned one, their less convenient aspects might have been noted in literary history. As Flora Watkins wryly comments: “slobber’d jowls” and “be-muddi’d bellies” appear nowhere in the play’s description of the breed.2

But sweetness was Tristan’s essential characteristic. Once, when I was teaching at a college that had experienced two suicides in a month, the students were despondent and angry. In addition to the ministerial sorts of care I offered them, I brought Tristan to campus for a day. He shambled around the classroom while I taught, nuzzling the undergrads, stuffing his curious nose into backpacks and purses, charming them out of their sadness.

* * *

As a general rule, Jesuits don’t have pets. They aren’t forbidden by our constitutions, and some of Ours who live independently in an apartment or a dorm suite may have a dog, though there is no reason for a Jesuit to ever own a cat, except perhaps to familiarize himself with Satan and all his empty works and promises. There is the rare Jesuit community that has a dog, but some of us have allergies to pets, and not all Jesuits are dog lovers. (Some people find the rampaging affection of dogs noxious. Explaining his preference for a pet lobster, Gérard de Nerval said: “They know the secrets of the sea, they don’t bark, and they don’t gobble up your monadic privacy like dogs do.”3) Even if every Jesuit in a house agreed to get a dog, communities are never stable, since men move in and out as they are missioned hither and yon. And the main problem of dog ownership is that apostolic work keeps us away from home much of the time. As for the dog, it would be unfair to subject it to the hazards of Jesuit domesticity: a menagerie of opinionated bachelors will all have different ideas about discipline and boundaries. If my Jesuit superior insisted on getting a dog for the house, I would argue against it (irresolutely, hoping to be overruled).

These are the obvious difficulties of introducing a dog into a Jesuit community. But there is a hazier problem. Is a desire for a dog’s affection a salutary or sufficient motive for working priests and brothers living in community?4 For Jesuits—men who live without spouses and without children, in shifting configurations that they do not choose—creating intimacy and long-term friendship can be a challenge. The temptation to displace affection onto a dog rather than one’s brothers can be great. On the other hand, the absence of pets does not automatically generate healthy community life. And it’s not a zero-sum game, anyway: dogs can bring life and affection to a house, and tenderness has a way of spilling over borders.

Spilling over is a good way to describe Tristan’s way of existing: saliva spilled over his jowls; his long, velvety ears spilled over his face when he would lay on his side; yards of extra fur collected around his neck and joints. When he flopped down, he would unfurl; asleep, he looked like road kill melting into the carpet. He also had extra affection for anyone, even cats. One snarling feline hissed at him and clawed his nose, causing a bloody gash. But Tristan didn’t even yelp. Because he was too theologically naive to know that cats are evil, he was simply astonished rather than defensive: “honestly, there is no reason for you to have done that,” his expression seemed to say.

Why is Jayme so mean? Tristan was so much nicer.

Mel / Flickr Creative Commons

The beloved, if ill-defined, place of a dog in our affections makes the problem of mourning for a dog complicated. It is easier to expect sympathy from others when we are grieving a friend or relative. But most people avoid the melodrama of announcing to acquaintances that their dog has died. John Homan, in his book What’s a Dog For?, notes: “Caring for a dog at the end of its life and grieving after it’s gone is in some ways more complicated than grieving for a person, because the question of what a dog is is far from settled.”5 I would press Homan’s point further. It’s not just a problem of essence (what a dog is) or function (what a dog is for). It’s a question of relationality: what our relationship with a dog means. The problem of mourning for a dog is bound up with the problem of believing that we love a dog. And love can mean lots of different things. The emotionally traumatized may find that it is a dog’s love that brings them back to life; the relationship that epileptics or the blind have with their dogs enables them not merely to survive but to flourish. Nevertheless, while dogs might offer us practical skills as well as something resembling unconditional love (they will play with us even if we’re ugly, insensitive, or sarcastic), dogs never challenge us when we’re being stubborn or petty.

Maelis / Flickr Creative Commons

There is no risk in loving a dog. And so what it means to love a dog is necessarily limited. There is something pathetic about Leona Helmsley—wealthy, tyrannical—clutching her dog and grinning at the camera. What does her love for a dog mean when she was so monstrous to the humans around her? It’s generally clear what we mean when we say that we love our parents or friends, because that love participates in, and derives from, divine love. It’s also clear what we mean when we say that we love nature, a movie, a book, or a sport, because that love is reverence for divine creation or the human genius that is its reflection. But when we say we love a dog, we’re not referring to a point that exists on a continuum somewhere between human-love and object-love. We seem to be referring to some other category altogether.

* * *

As we waited for the vet to come into the room, my brother asked me: “Are there blessings for dogs?” I had blessed Tristan during his last night as I sat beside him. I had not thought of how a priestly blessing brings grace not only to those who are blessed, but to those who witness it. (Ordained last year, I’m still getting the hang of being a priest.) So Tristan got another blessing out of me, to ease him gently back into the dust from which God made him.

An unintentionally hilarious moment occurred after the lethal injection, when the kindly vet, looking into our tear-streaked faces, asked if we wanted a clipping of his hair. We burst out laughing. Every corner of my brother’s house is a museum to Tristan’s hair. Shedding was his exercise.

When I am asked about the joys and difficulties of Jesuit life, I reply that the only thing that I consistently miss about my pre-Jesuit life is my dog. In the weeks before I entered the novitiate, in the midst of gleefully discarding my useless stuff, the only difficult matter was figuring out what to do with Tristan. Concerned about abandoned dogs, the breeders had made it clear when I bought Tristan that they would always take back their dogs no matter how old. Tristan would not have cared where he was dropped off, in spite of our sentimental notions of dog ownership: dogs are happy wherever they are fed and petted. But if I had given Tristan back to the breeders in Texas (my family and Jesuit life are in the Midwest), I would never have seen him again. I sent an all-call to anyone in my family who wanted an extra dog. But, unburdened by my adoration of bassets and of Tristan in particular, most of them very sensibly declined to have their furniture mauled, their houses smelled up, and their walls drooled on by a hulking, ungovernable mud-magnet.

My brother and sister-in-law said they would take him, to my great and selfish relief. (I gave them my grand piano as thanks.) They never seemed to be reluctant about it, but they must have taken a deep breath before offering to give Tristan a home. My sister-in-law keeps a very neat house, and so I cringed when I visited their basset-infected home: Tristan would shake his jowls and slobber would fly up to the ceiling; my nephew would pet him, and sheets of hair would float into the atmosphere; over the course of a decade, their off-white carpet turned to a mottled beige. They joked about it all, but they never complained. And in the end, they came to love him more than I did. Living with his even-tempered sweetness for years, they discovered quirks about him that I had never noticed. And his death left a hole in their daily routine, an absence that affected them more than me. That they would take in a filthy, slobbery dog for my sake was not just a one-time decision that freed me to enter the Jesuits without regrets, but an eleven-year act of mercy. And it taught me more about love than any adorable thing Tristan ever did or could have done.

The trip to my brother’s house to put Tristan to sleep turned out to be unexpectedly complicated. I was far away, celebrating the ordinations of Jesuit friends, a happy time for Jesuits and their families. Tristan’s health was failing, and so I was awkwardly texting under the table and in the bathroom, arranging logistics, afraid to spoil the mood with the potentially ludicrous announcement that my dog was dying and so could we all please just stop having fun? My brother made the vet appointment for the day after I was supposed to arrive home. But I missed the last connecting flight out of Chicago, and the airline could only offer me a flight for the next day. If I wanted to get there in time, the only option was to rent a car and drive seven hours through the middle of the night.

I showed up at the rental agency without a reservation. They had one car left, an SUV the size of a courthouse, with a three-day-rental requirement. But the logic of grief had already taken over. In retrospect, my vow of poverty sits uneasily with my decision to spend such a preposterous sum in order to witness the execution of a quivering bag of bones. But what can I say? Tristan was the only living thing on the earth that I could call my own. And I loved him.

— — // — —

- I pause here to commemorate Machen, our family dachshund who was occasionally mean, though not vicious (we thought). One day she trotted over to our neighbors and ripped their elderly, blind dog to shreds. She came home smacking her blood-stained jowls, fresh poodle-meat her last meal before the tumbrel ride to the guillotine. I hope she thought it was worth it. ↩

- Flora Watkins, “The Brilliant Basset Hound.” Country Life (UK) 25 Oct. 2012. Web. www.countrylife.co.uk/countryside/article/530429/The-brilliant-basset-hound.html. ↩

- Originating with Guillaume Apollinaire, this oft-quoted story of de Nerval’s lobster which he walked on a blue silk leash is surely apocryphal. See: www.museumofhoaxes.com/hoax/weblog/comments/nerval_lobster. ↩

- I’m only considering Jesuit life here, since there are religious orders that make dog training part of their ministry, such as the Monks of New Skete. And I’ve been told that after Vatican II a number of Jesuits went out and got dogs. But that was the 70s. Things were weird then. ↩

- Quoted in Walter Vatter, “Made for Each Other.” New York Times Sunday Book Review 4 Jan. 2013. Web. www.nytimes.com/2013/01/06/books/review/whats-a-dog-for-by-john-homans.html. ↩