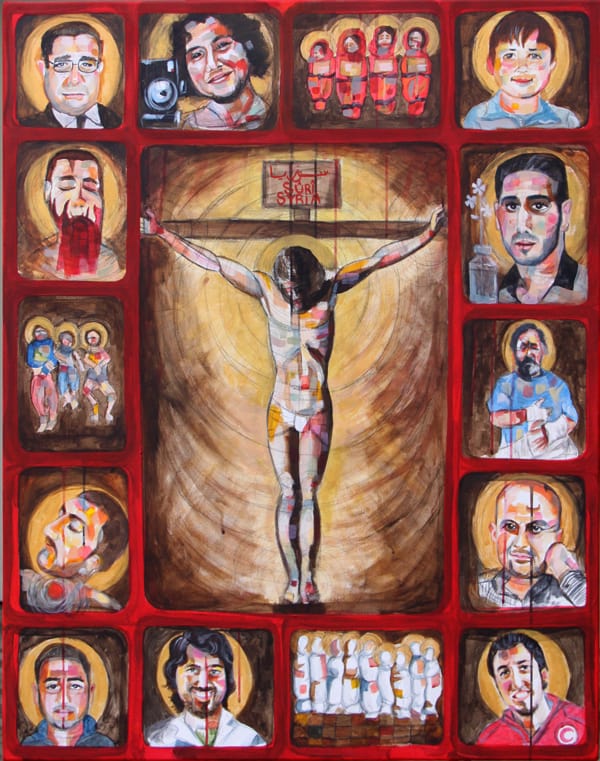

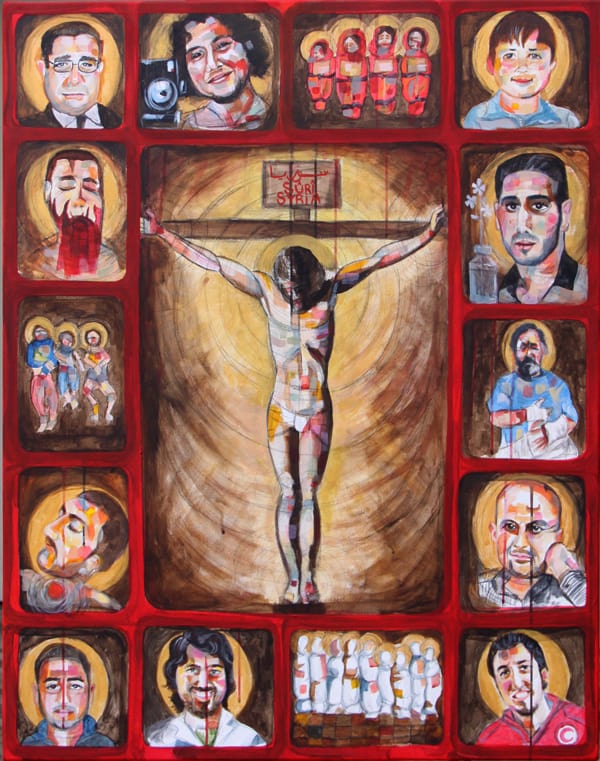

Passion de la Syrie by Samer Tarabichi

I arrived in the States last August during a crucial time for my homeland. Suddenly it seemed that Syria was all over the headlines; wherever I went everybody was concerned about Syria. Here in America Syria was being discussed because President Obama had yet to decide whether to intervene militarily, and it was being discussed because two Jesuit leaders, Pope Francis and Adolfo Nicolas, were making international calls for prayer and assistance. I remember especially all the questions posed to me, as I if were a political analyst… What should be done? Should troops be sent to intervene? How can the violence end?

Everyone, it seemed, wanted my opinion. But I didn’t know what to say. I still don’t. In my confusion I found myself replying not with policy analysis, but with another question: what is the alternative to intervention?

What was on my heart as I asked my own question was this: people are suffering. Now. Normal people, everyday people. And the questions that spin through my mind are about how to end the suffering of these innocent people, people who otherwise become just numbers – ever increasing numbers. I was afraid it would not stop without intervention.

Sadly, it seems that my fears were well founded. After all the discussion in the headlines and in conversations, after the waves of condemnations grew calm, still there has been no solution. And now the conflict in Syria seems to have reached a point of no return. Now the conflict has become a question of survival, where none of the many sides are willing to concede anything because to them any step back means a step closer to losing.

Even writing such words feels like giving in to the cynicism of the situation. It is cynical to speak about winning and losing while the innocent people, the ones who were forced to quit their homes under the unmerciful fire, the ones who are the actual biggest losers, are ignored.1 How can I remember them? By praying.

It seems like a small response to cynicism, yes. But, yes, again it is time for prayer, if for no other reason than because through it we can practice believing that order can be brought to chaos; that there can be a better-than-before. Again it is time for prayer. Only this time, I thought to myself, to overcome such cynicism I must pray with people, with faces – faces that have become the icons of the ones who have truly lost.

It was the Washington Post who provided me, at just that time, 18 such icons to pray with. These icons are not ancient and did not take months to draw. No, these modern icons are photographs of real people, people I hope are still alive, people who have names and stories to tell, stories of faith and hope and love – at least these are the stories I see as I look at these photos like icons.2 In particular, three of these faces stood out – and in them the three cardinal virtues: faith, hope and love.

I see faith in Mouneer’s eyes as he sits behind the sewing machine, believing that the $50 dollars in his pocket will provide for the whole month. I hear hope in the cry of Khalid who was born in a Zaa’tary camp, a Syrian who perhaps one day will smile as he sees his homeland for the first time. I see love in Baraa’s wound, a sniper wound, received as she and her family were fleeing Aleppo – my own home town.

It is not always easy for me to see faith and hope and love in these living icons – sometimes I just see suffering. But the virtues are there, too, if I can see clearly. Which I why I would like to share with you three keys, three ways Mouneer and Khalid and Baraa have reminded me of what it is the cardinal virtues ask me to believe: that suffering is not the end.

***

Mouneer – Faith: “Whom have we but Allah?” This is a Syrian cry – a Muslim cry – that echoes like one of the verses of the psalms (e.g., Ps 5:2-3). The majority of Syrian refugees are, like the majority of Syrians, Muslims. It is these Muslims who have taught me how not to lose faith in God. God is merciful, this is what Muslims believe, and since many have been abandoned without any support, they direct their cries to the one whose heart feels their suffering, you, God. They know that, even if the world forsakes them, still, God, you will help them. This I see in Mouneer.

***

Khalid – Hope: I am Syrian, and I know my people well. Which is why I notice that in the stories we tell there is an optimism, a longing for a better future. I see it in those who won’t give up even in catastrophic situations, and in those trying to find a job under hard circumstances. I see such hope in all those who wait for the moment they will be back home again, when they can rebuild, restore, and remember not only their exile, but also that God redeemed and protected them (e.g., Ps 124:2-3). This I see in Khalid.

***

Baraa – Love: One can’t deny the tone of revenge that arises among a wounded people, and this is true in Syria there is no denying. The forgotten often feel not only that nobody is listening to them, but also that everyone support the others, that everyone is an opponent. It is real this ferocity, but I am not afraid of it. Because simply it is not authentic. It is not true to our Syrian heart. As a Syrian I read the anger of God this way as well (e.g., Hosea ch. 2), and even Jesus’ own anger (e.g., John 2: 13-25) – yes, the feeling is real, but must it lead to vengeance? Surely not. Vengeance is not authentic to the heart of God; hate is neither Divine nor Syrian. Which is why, amidst violence and the talk of vengeance, I still believe that we may have a tongue to hate – but not a heart. Love will rule once again after anger and vengeance has faded. We will live together again, as we have for centuries. This I see in Baraa.

***

A few words as epilogue, if I may.

As I finished writing these words about my efforts to pray with these living Icons, I suddenly realized that this whole idea of seeing modern people as living Icons was inspired by a real Icon. I keep it in my room wherever I am living and take it with me as I travel. It is an Icon drawn by another young Syrian man, a physician and artist from Aleppo who is living now in France named Samer Tarabichi, and you have seen it. He has very kindly allowed me to use it at the outset of this essay.

If you look again you can see that in the Icon Dr. Samer has drawn we see Christ, the crucified, surrounded by Syrians who have been killed or arrested in the last few years. For Dr. Samer, Jesus is the source of love, a love that can bring new life to everything around it and change it for the better. The martyrs who surround him represent the colorful spectrum of Syrian society: Christians and Muslims, Kurds and Arabs, children and adults and elders. All are represented here and for Dr. Samer all share in Jesus’ mission of love in that they have given their lives to change the old Syria. Notable among the circle of martyrs is the first physician killed during the conflict (while he was trying to save another’s life), a photographer who tried to tell the truth of what was going own, children tortured and killed in a massacre, peace activists, and even a famous singer.

If you look back at Dr. Samer’s Icon, or at the the many iconic pictures of Syrian refugees, I ask you to please pray for my people. If you do, please ask God to give us what can indeed be seen in Mouneer, Khalid and Baraa: faith, hope and love. Thank you.

— — // — —

- In my digital search for connection with just such people I discovered a video that was made by British artists to raise awareness about Syrian refugees. I watched it again and again. if you have time, I recommend it: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=un4cZOKFK3M&feature=share ↩

- The photos and stories are by journalists Linda Davidson and Kevin Sullivan. For me these two are a great gift. They have been evangelists for me because, just as the evangelists gave us the story of Christ to enter into, so these journalists have given me stories to pray with. I would like to thank them: thank you, Linda and David, your work is a gift. ↩