Perhaps one of the most frustrating things about the rule of law is that, despite our best attempts, it suffers from the (unwritten) laws of unintended consequence and perverse incentives. Because the legal system requires people to actually put it into practice, all the flaws and foibles of the various individuals involved affect how the laws are implemented. This is abundantly clear when the law starts to intersect with issues of poverty, race, and domestic violence.

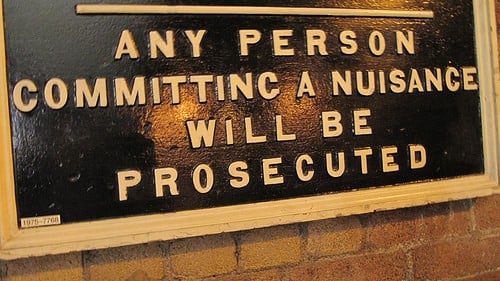

Take the issue of so-called “nuisance laws.” These are often local laws aimed at reducing criminal activity by moving it out of residential neighborhoods by giving landlords the authority to evict individuals who have had police visit their homes a certain number of times. The idea is that if someone is using his home to deal drugs or run a robbery conspiracy, get him or her out of there.

The reality of how these laws are used is often quite different, however. The New York Times recently reported on how these laws work to punish victims of domestic violence. Lakisha Briggs, a victim of domestic violence profiled in the piece, was faced with the unimaginable choice of either allowing her abuser to remain in her home (and to continue to abuse her without fear of the police) or get evicted. Slate.com reports that the Ameican Civil Liberites Union has now filed suit on Briggs’ behalf and that the case will proceed to trial soon. But this is part of a troubling trend of “third-party” law enforcement, enlisting landlords, employers, and others to do the difficult work of policing. Lakisha thus became a victim not only of her abuser, but of a law intended to protect her.

This is the really insidious aspect to these laws and how they are enforced: the dehumanizing reduction of victims into just another problem to be dealt with. One ACLU lawyer put it this way in the Times article:

“The problem with these ordinances is that they turn victims of crime who are pleading for emergency assistance into ‘nuisances’ in the eyes of the city,” Ms. Park said. “They limit people’s ability to seek help from police and punish victims for criminal activity committed against them.”

Compounding the issue, they give all the power to landlords who are incentivized to just make the problems go away. As Dahlia Lithwick remarks in her article in Slate:

The Norristown ordinance and its counterparts across the country don’t simply imperil poor and vulnerable women because they force the women to choose between being abused or being evicted. It also makes their landlords the unwilling arbiters of whether and when the women deserve that protection in the first instance. Policing domestic violence disputes is one of the most difficult things our law enforcement officers are tasked with. Contracting that out to landlords is not the answer.

These situations are appalling. We certainly don’t want to ascribe evil or malicious intent to officers trying to clean up blighted neighborhoods or prevent criminal commerce. But these abuses are real, and they have their most dangerous effects on minorities, low-income individuals, and especially women. Without a deeper understanding of the realities of poverty and domestic violence – and without adequate funding and training for local law enforcement to actually engage these communities in a supportive and rehabilitative manner – we run the risk of re-victimizing the very people we want to protect.