So the Black Death hit SoCal. Sort of.

Over the last few weeks, media outlets worldwide have reported that parts of the Angeles National Forest in Los Angeles County were shut down when a squirrel was discovered to be carrying a variation of the bubonic plague. No humans were infected, but the mere mention of the black plague was sufficient to prompt several pre-emptive campground closings, trigger reassuring press conferences from park officials, and send media outlets scrambling for stock footage of squirrels and presumably combing Wikipedia articles in order to figure out how to actually spell Yersinia pestis, the bacteria believed by most scholars to be responsible for the epidemic that ravaged Europe in the mid-14th Century.

This media frenzy over one sick squirrel wasn’t just the result of a slow news cycle. It suggests the impressionability of collective cultural memories. While Europeans suffered a recurring cycle of plague throughout the medieval and early modern periods, the epidemic that most people think of as the plague was the Black Death that ravaged Europe between 1347-1351, killing an estimated third of Europe’s overall population and as much as 80% of the population in some places. (14th century records being what they are, these numbers are ballpark. It’s enough to know that a lot of people died.)

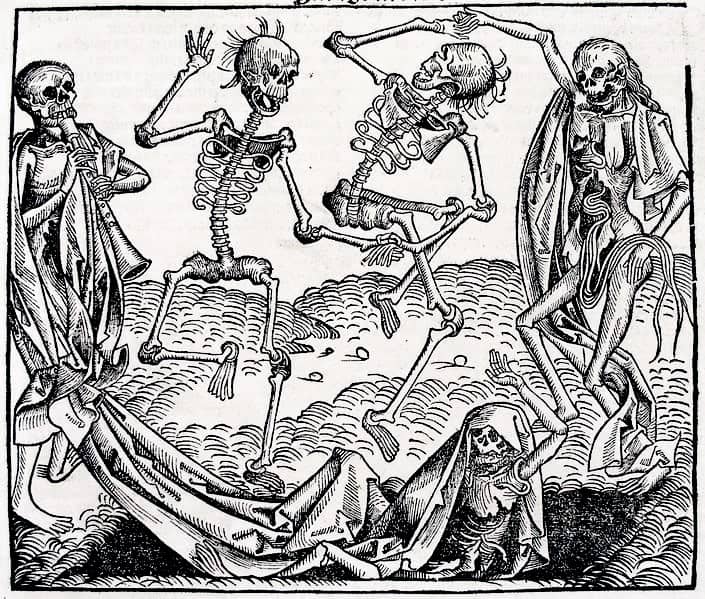

My danse was macabre before it was cool.

The long-term implications of the 15th century plague may or may not be interesting (you’d have to ask my high school students in a few weeks to see whether I manage the trick). However, it’s absolutely worth noting that the memory of the Black Death imprinted itself on the collective memory of Europeans in ways that were passed down for centuries to come. Visual arts took up the theme of death in Europe, exemplified by the Danse Macabre or the “Dance of Death,” while Pieter Brughel’s “The Triumph of Death” gave the morbid fascination with death a full color treatment. Two and a half centuries after the plague, Shakespeare’s Mercutio could declare, “a plague o’ both your houses!” in Romeo and Juliet. And, most impressively, the collective memory of the disease is potent enough that over six and a half centuries later, in a century that has seen warnings of SARS, swine flu, bird flu, and other possible epidemics, a single woodland rodent carrying plague bacteria is enough for the Atlantic to bawl in a (calculatedly hyperbolic) headline: “A U.S. Squirrel has the Plague: Are We All Going to Die?”

Cultural and collective memory is a desperately tricky thing. When memories arise, the echoes carry with them distortions of distance and misremembrance. However, in a culture in which historical amnesia is often lamented, it is well worth it to mark a news item in which the echoes of events from the distant past arrive out of memory to take on present-day urgency.

***

Squirrel photo courtesy flickr user ogwen.

Danse Macabre: The Hipster courtesy flickr user Dylan Meconis