I recently turned 30. Aside from the creeping guilt that I haven’t done anything of note (use this website when you are feeling a little overconfident), I also felt the impending doom of my body falling apart. From some reason, the need for regular colonoscopies and hypertension meds seem so much closer now that my odomoter has clicked into its fourth decade of life. So I took my birthday (and my rising sense of dread) as an opportunity to get a full medical check-up that would counteract the false prophets of doom with data. Surely those sweet, glorious numbers would tell me that I had nothing to fear.

Arriving at the Doctor’s office, I hopped up on the examination table – lined, of course, with the paper equivalent of single-ply toilet paper and raised to a height specifically designed to make my feet dangle like Edith Ann. This height of uncomfortability having been reached, I was never the less unphased. I was there for vindication. And that’s when I saw it. A BMI chart where, according to my height and weight, I was a just couple more ice cream cones away from being “overweight.” I had to be seeing this wrong. Not me. So I clambered down off the table, crumpling the tissue paper accordingly, and looked more closely – slowly tracking the x-axis up to my exact height, running my eyes across the chart to find exactly where I landed (apparently with a bigger thud than I originally thought) on the y-axis. And sure enough, there I was again, teetering close to the yellow warning zone. Somehow I had moved immediately from too-skinny-to-get-a-girlfriend-in-high-school to too-fat-to-wear-swim-trunks-in-public, without any of the glorious transition. It was like going from Baltic Avenue directly to Jail without passing Go! and without collecting $200 (stupid vow of poverty).

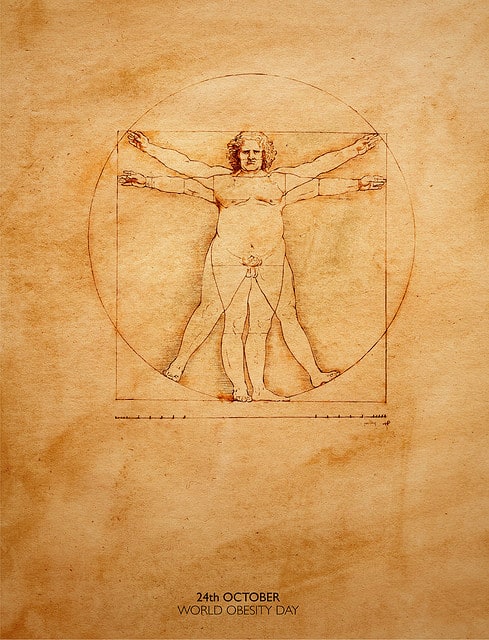

So the numbers that I was hoping would release me from my preoccupation with turning 30 instead threw me into a bit of a tailspin, fair enough. (Part of tailspin was brought on by the guilt from this very website. I loathe exercising. Certainly yoga, but spinning even more. We get it guys – you are so spiritual and corporeal, all at the same time. You’re amazing. I can’t wait for the insight of “Finding God when I run.”) But why a tailspin? Most everyone knows that BMI is a horrible way to determine obesity. I was less concerned about my weight and more concerned about what people would think of me if I really were fat. And let’s not pretend that people don’t care. I am not proud of it, but I am one of those people who casts judging glances at the overweight.

Suddenly I was right in my own crosshairs.

***

Maybe intolerance or bigotry is too strong to describe what happens. Maybe bias, or judgment, better describes what happens when those adjectives rise up unbidden inside your head before being stuffed right back down again. Most of the time we are scared to admit it’s happening because we are afraid it makes us bad people. Well, self-deception doesn’t make us any better, so why not admit it is actually happening. I don’t recommend proclaiming it to the entire world (like I am right now), but we can start by admitting it to ourselves.

So here goes nothing: when I see a fat person I often think that they are lazy or lack willpower. If I see a fat person sitting down to a huge burger and shake, I can easily slip into more intense judgments about their character. Everything I’ve learned from my public health education tells me that I shouldn’t jump to these conclusions, that I shouldn’t have these thoughts. But I do. What gets etched into us over a lifetime is not so easily smoothed out. No matter how much we try to dislodge it, sometimes the best we can hope for is to minimize its impact on our behavior.

Moreover, if I do slide from the green zone into yellow or red, the judgment that I feel toward others will easily translate to an internalized judgment of myself. It is like when Archbishop Tutu describes hoping his pilot was white when his plane hit turbulence because he had been so trained to think that white people were more competent than black people.

***

Are all our silent judgments groundless? In many ways, no. Population-level trends are common and there are often negative truths we must face. There are reasons why the growing (pun intended) obesity problem in the United States gets so much attention. Obesity is a risk factor for many diseases and ends up costing over $100 billion annually in direct medical costs. There is an even greater indirect cost, including: lower school attendance, lost economic productivity, premature death, higher transportation costs, and on and on.

Even at the individual level, obesity can clearly be a problem. From less schooling, to more medical costs and greater likelihood of early death, the obese are more susceptible – something that should be a problem for those of us interested in the human person being fully alive. And at the social level, obesity is equally troublesome. Absenteeism at work, ineligibility for military service, and increased jet fuel costs all mean that everyone has to pay more, in both time and money, to accomplish our shared goals.

Of course these effects do not impact every overweight person; they are aggregate concerns. But our silent judgments about people are rarely as well grounded as these concerns. Epidemiologists can tell you how difficult causal relationships are to prove. Beyond health, contentious debates such as taxation-job creation and fossil fuels-climate change pivot on our inability to prove causation. So why is it that my judgments about causation feel so certain? They are overweight because they are lazy. They are addicted because they are weak. They have HIV because they are licentious.

***

Not too long ago we believed that health and disease was rooted in the supernatural. If you got sick, we used to believe that you (or your ancestors) had done something wrong. Fever? What about that chicken you stole from the neighbor? Vomiting? Remember that time when you cheated the lord on taxes? Your son has gone mad? Didn’t you sleep with your sister-in-law? Sickness, health and morality were a tightly woven trio not so long ago in our human history.

It wasn’t until the mid-19th Century that germ theory came along and we slowly accepted the idea that microorganisms cause disease. Suddenly, the thread of morality was pulled away from its partners, health and disease.

But that separation was clear when infectious diseases were the leading causes of death. People weren’t blameworthy when they contracted tuberculosis, cholera and scarlet fever (which might be the 1850’s equivalent of leukemia and Alzheimer’s, and you’re not going to blame someone for getting those diseases, are you?) But the leading causes of death in the U.S. are no longer infectious diseases. They are now chronic diseases, diseases that are more rooted in behavior than bacteria and viruses. So, we might ask: why not blame someone for his or her heart disease or type-2 diabetes?

Hopefully we’ve learned, from our experience with germ theory, that disease is complex. After first relegating disease to moral culpability, then wedding it to microorganisms, today we typically break causes of disease into three categories:

- Natural lottery – we don’t choose our genetic make-up, but it might be more connected to obesity than we think

- Social lottery – we don’t choose where we are born, but it sure has a huge impact on our probability of diabetes and obesity

- Personal choice – even with all other factors equal, nobody can force people to make the right decisions about their health

***

There are as many explanations for the rise in U.S. obesity as there are diet pills on Amazon. Some point to subsidies for unhealthy corn syrup or unhealthy lunches in our public school system, others to neighborhoods where it is unsafe to exercise. Some say it’s because kids play video games too often or that we lack the will to eat well and exercise properly. Still others attribute obesity to the breakdown of the nuclear family (because we’re eating fewer meals at home).

It’s not hard to see who looks where for their explanations of the obesity epidemic. Those on the left prefer explanations rooted in the social lottery. Those on the right prefer explanations based in personal choice. Of course those are broad generalizations, but they’re not entirely inaccurate either.

The highly individualistic culture of the United States makes the social lottery explanation far less popular than the personal choice theory. We like to believe that if you just pull hard enough on your bootstraps that you can achieve your goal. It’s essentially that very attitude that rises up in me when I see fat people and make judgments about their laziness or lack of willpower. But facts are dangerous things, and we know that although social setting does not solely determine your health (there are lots of poor and uneducated people who are healthy) it does have a very strong influence on it. And we ignore that reality at our own peril.

If we are able to accept both the social lottery explanation and the personal choice explanation as legitimate ways of understanding obesity, we move closer to two very desirable ends. First, we have a greater chance at reversing the epidemic in our country by funding prevention rather than treatment. Second, we have a greater chance at reversing the snap judgments we make of others.

***

We have a lot of problems in our country that aren’t going to solve themselves. Obesity is just one of them. But many of them, in fact, tap into the same tension that colors our debate over obesity.

This is a tension that simply does not sit well with the American because it requires that we believe that two things we would like to keep apart – personal responsibility and public responsibility – must instead be held together. While we often prefer to view them as opposing ideals, the example of obesity shows us that causes, consequences, and solutions are both individual and communal.

Yes, it would be a whole lot easier if I could just trust my reflexive reaction when I see a fat person downing supersized McDonald’s fries and a Shamrock shake; it is easier to blame him or her and move on. But, whether you are wholly a bleeding heart or completely self-interested, you have a stake in reversing this crisis. There’s plenty of blame to go around for our growing waistlines, but we will be better off when we admit that this big fat problem is not just theirs, but ours.