“Pray, hope, and don’t worry” was Padre Pio’s famous maxim for living the Christian life. It’s good advice, if a bit hard to follow. Two out of three is a good day, for me at least.

Since January of this year, the NYTimes Opinionator blog has been running a series of entries on anxiety. They’re a loosely allied constellation, grouped under this heading:

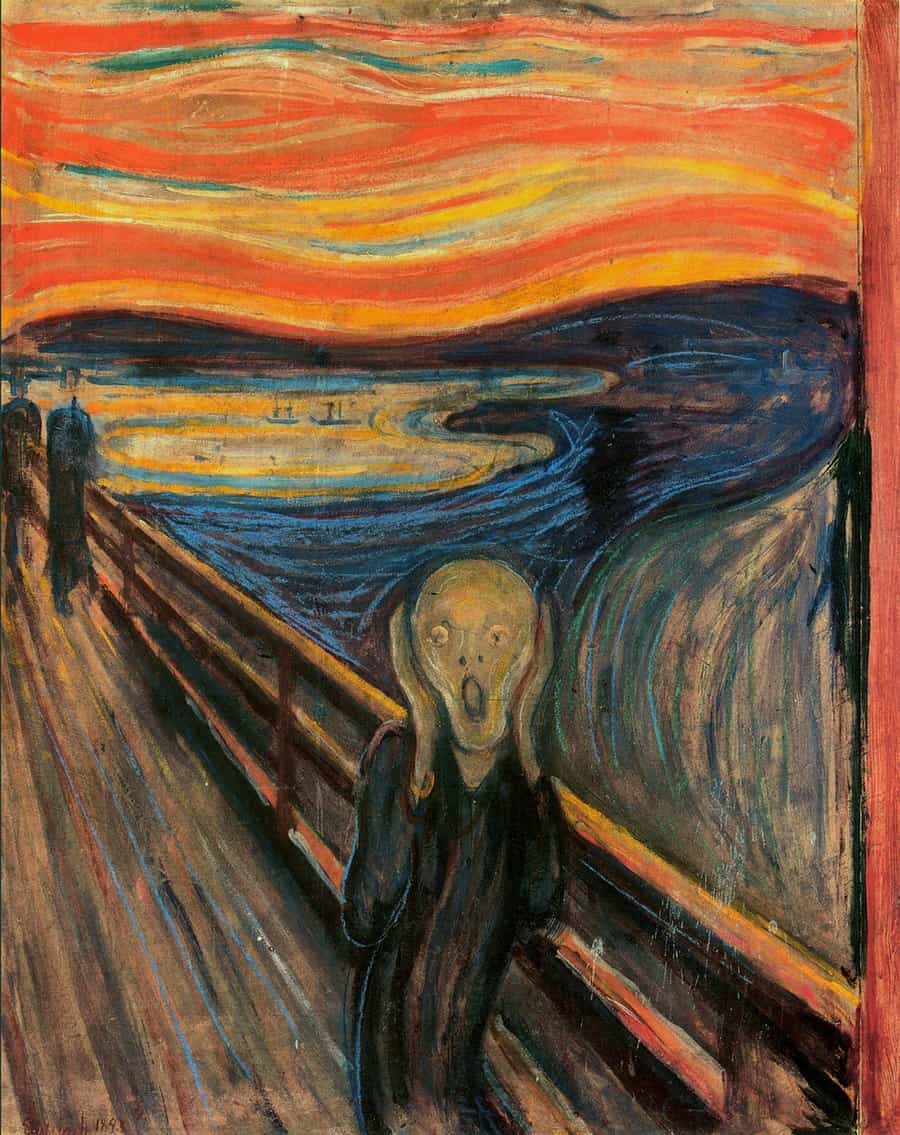

We worry. Nearly one in five Americans suffer from anxiety. For many, it is not a disorder, but a part of the human condition. This series explores how we navigate the worried mind, through essay, art and memoir.

The news that human beings are prone to worry hardly counts as breaking, on the web or anywhere else. I keep coming back to Gordon Marino’s cutely-titled post “The Danish Doctor of Dread.” Though both have written about angst, Marino is referring to philosopher Søren Kierkegaard (1813-1855), not our own Jim Keane (1974-present). This is partly because I have spent a fair bit of the last two years studying the Great Dane.

For Kierkegaard, anxiety was “not a disorder, but a part of the human condition;” a part of human life that he examined under the bright light hazy, opaque light of philosophical reflection. In “The Concept of Anxiety,” Kierkegaard maintains that “anxiety remains…a matter of the finite mind horrified at its own limitlessness.” It is our freedom, in other words, not our confinements, that makes us anxious.

But there’s another type of anxiety that obsessed Kierkegaard throughout all of his works—one Marino doesn’t consider: the anxiety of a life devoid of ultimate meaning, one lived arbitrarily and without any serious existential commitments. For Kierkegaard, anxiety attends the life lived without God.

Understood this way, anxiety is a symptom that points out a void within us that only God (or as Kierkegaard puts it, “the God-relationship”) can fill. Paradoxically, this type of anxiety can be a good thing, provided we recognize it for what it is: a call to greater reliance upon and intimacy with God.