The iconic Mr. Dimon

I know it’s gauche to start a column by suggesting a variant title (as it is to start with the most selfish letter in the English alphabet, I suppose), but… but, if I’d written about the immortal Mr. Dimon this past spring I definitely would have pushed my editors to use the title “Angel or Dimon?” This because Jamie Dimon, the chairman and CEO of JP Morgan, had a controversial spring.

For months he’d been engaged in an all-too-public fight to keep both his jobs. There were talks of the merits (or lack thereof) of splitting the two jobs,1 there were stories about the many departures of execs at the bank over the past couple of years, there was… well, there was a lot. Since the JP Morgan CEO was clearly being painted as the bad guy, why not go with the demon pun?

But you know, had I written this piece a couple of years rather than a couple of months earlier, I’d have gone for a different hommage-de-plume entirely: Dimon/diamond would have just been too hard to resist (what’s the better title though? “Shine Bright Like J. Dimon”? “Lucy in the Sky with Dimon”? A “Sweet Caroline” cover by J. Dimon? Okay, yeah, enough). Back then, Dimon was almost universally adored, and in the post-“financial crisis” that was quite a feat for a banker. There were NY Times cover stories of Dimon’s clout at the White House, of his influence on and off Wall Street.

But now’s now, and both the chameleonic J. Dimon himself and popular opinions of him have continued to change with the times. Popular mood swings, enormous clout, scads of cash – I’ll admit: I’m fascinated. Even more, I’ll further admit that, as I (infrequently) pass JP Morgan’s headquarters on Park Avenue, I secretly hope to meet Jamie Dimon, even catch a glimpse of the man. After all, he’s an icon of 21st century finance.

What better title than “The Iconic Mr. Dimon” then?

How I Met Jamie Dimon

Well, it’s not like I’ve met him in person. I’ve more… read about him… whatever.

I first encountered the many-faceted name of Jamie Dimon in 2005, in the financial news pages, when he levitated up a few floors to the top job at JP Morgan. Even back then he stood out among the CEOs of major banks in the early and wild days of the 21st century. Just looking at Dimon and some of his fellow CEOs, JP Morgan’s top man was already remarkable. He seemed more affable than his peers at Citibank (Charles Prince) or Bank of America (Ken Lewis). He was younger than Morgan Stanley’s John Mack. He managed a firm that had a much broader business model than Stan O’Neill’s Merrill Lynch or Dick Fuld’s Lehman Brothers. And one look at him would cast doubt on suspicions that he and Bear Stearns’ James Cayne shared a burning passion for playing bridge. No, Dimon seemed to be the first of a new generation of Financial Lords of the Realm. And eight years later, out of all the CEOs I just named, Dimon is the only one still at the helm of a major bank.

The changing logo of JP Morgan Chase

And what a bank! The history of JP Morgan Chase Manhattan Chemical Bank (or whatever its actual name may be this week) is so intricate it ought to be made into a soap opera. JP Morgan was both a very storied and a very respectable institution, one deserving most if not all of its names, when Mr. Dimon took over in 2005. One of a small handful of banks involved in retail and investment banking, JP Morgan was a behemoth, and yet seemed perpetually the underdog. Behemoth and underdog fit not only JP Morgan itself, but Mr. Dimon as well. As was the grandson of a Greek banker with an undergrad degree from Tufts, Dimon did not have the usual Wall Street pedigree. Still, he worked his way to Harvard Business School and to the CEO job at Chicago’s Bank One. JP Morgan bought Bank One in 2004, opening higher ranks for the ambitious Dimon.

It’s not that Mr. Dimon disappeared after the initial flush of attention that accompanied his rise to power, it’s more that he wasn’t the top dog on my radar screen, until my second “encounter” with Dimon. It was at a gym in San Jose, California, early in the morning of a 2009 school day. I was listening to Gillian Tett’s Fool’s Gold during my work out, when Jamie Dimon again burst onto the scene.

Tett was telling a more or less mundane story detailing the cost of landline phones at JP Morgan’s London office when it happened. In the process she also spelled out the purity of Dimon’s professional background with the inclusion of one name: Sandy Weill. Dimon, fresh out of business school, no polish on his name at all, had been Sandy Weill’s lieutenant. A word, then, about Mr. Weill. Sandy Weill is the guy who created Citigroup, practically inventing the modern category of retail-investment banking juggernauts (of which JP Morgan is now part) in the process. Weill has a legendary reputation, as much of a strategic genius as a financial shark, he’s known as a ferocious deal-maker and a tough-as-nails boss.

Weill’s name explained EVERYTHING. I suddenly understood the deal about this Dimon character, and boy, the adrenaline almost made me lose my footing on the treadmill, crash my head on the railing, and spit me out to the back of the gym. This moment, to me, was akin to the “I am your father” moment for Star Wars fans: I was shocked and awed at the same time. No doubt Weill was a great and influential mentor, but the proximity of two Financial Lord sized egos must have caused a larger than normal explosion at some point. Suffice it to say that Dimon and Weill clashed. Dimon was fired.

People like Dimon land seem always to land on their feet. He certainly did: after about sixteen months, Dimon became his own boss at a small regional bank. Which merged with Bank One. Which merged with JP Morgan. And when the smoke cleared on the year 2005 there stood Jamie Dimon, king of one of the largest banks in the country.

(Financial) America’s Idol

The rest of Tett’s book was even more exciting (hence the need to listen to it off of the treadmill – the risk manager in me felt it was safer that way). Tett explained how Dimon managed to be a winner in the losing game of the mortgage crisis. While a lot of credit is given to Dimon’s subordinates (who created a smarter-than-most derivatives division) my 2009 self found it amazing to see how much damage CEOs can actually do. After all, no one was really excited about Citibank’s Church Prince once he said that he’d keep dancing as long as the (subprime) music was on: what makes for a good leader is not a decent ear or even a nice two-step, but the ability to have and enact a vision.

It’s not just Church Prince who turned out not to be the future of American banking. Amongst the seemingly self-sabotaged we must also count Ken Lewis (who bought the subprime mortgage specialist Countryside at the worst possible time), Merrill’s Stan O’Neill (who sounds in the book like he’s doubling down on subprime and losing track of every other division of his bank), and I’m not even going to open the file of Lehman Brothers’ CEO. Not only did Dimon sabotage neither himself nor his bank, he actually made the deal of the decade, if not the century: he bought Bear Sterns.

Imagine Dimon making it back home that evening:. He walks in and wife says “Hi Hon’ how was your day?” He responds, nonchalant “Pretty good, I bought this, and got a great deal on it too”:

Bear Sterns building NYC

Now, I am not arguing to the morality of the deal (that would be for a separate article, Paddy Gilger, SJ). I am here simply saying that there were only a very few financially-sound deals to be made during the crisis. And Dimon hooked the big one in Bear Sterns.

Not only had Dimon become a financial whiz but, in the early days of the Obama presidency (Part I), Dimon was a political favorite as well. By mid-2009, it seemed like the man had done it all: managed the crisis, helped his bank’s bottom line, made key political allies. And all while doing America a favor by, say it with me now, doing good business.

There was only one problem. There’s only one place to go from the top.

The Fall

While most of the business world has enjoyed a return-to-partial-sunshine over the past couple of years, those years have been hard on JP Morgan – and on Dimon in particular. He’s lost both respect and money since 2009, neither of which have been easy in the leaving.

Money first. Business-wise, Dimon oversaw the infamous London Whale trader fiasco cost his bank some six billion dollars (and yes, that’s Billions with a B). It also cost Dimon some of his own lieutenants – Ina Drew and Stephen Black. Drew, who departed in 2012 as a result of the huge loss under her watch, is one of the most accomplished women on Wall Street. Drew had started at one of JP Morgan’s ancestors, called Chemical Bank,2 and had showed competence and finesse in climbing the ladder. She was a key insider as well as a standout figure. Stephen Black, one of Dimon’s closest advisors and allies during the hectic days of the financial crisis, left in early 2011 probably to avail himself for a CEO job. The bank’s huge loss and Dimon’s unusually hesitant management of it exposed it to many criticisms, which led to more departures, more internal fighting, and plummeting relationships with both Capitol Hill and Pennsylvania Avenue.

Respect next. Dimon, the All-American CEO has taken a few hits, and become a favorite target of politicians. This spring’s governance fight over the CEO and Chairman of the Board roles seemed to add another layer to the public relations fiasco that JP Morgan has been enduring over the past year and half. And it’s not like the past eighteen months have been easy for banks in general. The most recognized banking brands have been tainted, if not by the Libor scandal3 then another scandal of the same kind. All of these scandals basically amount to industry-wide price-fixing – and, as much as JP Morgan was able to positively standout of the pack during the financial crisis and its immediate aftermath, it’s been struggling harder than anyone else over the past year and a half, now dealing with London Whales, massive exec turnover, and all the questions that come with this kind of issues.

And what goes for JP Morgan goes for Jamie Dimon. Dimon acknowledged overconfidence and lack of common sense at the firm he heads. At the same time, he’s lost his professional allies, and saw his personal political capital moving from political courtesan to populist target. It’s been a wild ride for the Tufts turned Harvard man.

Icon?

The past six years have shown that even if Jamie Dimon is not America’s banking idol (I wonder what that show would look like? – you’re welcome to send ideas to qdupontsj@thejesuitpost.org) he is and remains, an iconic figure in 21st century American business.

Whatever my engineer dad says, the standout American business of the past fifty years has been banking. And banking has always got to have its Charles Erwin Wilson, the one face of the industry that people love to quote or misquote, even out of context. Chuck Prince’s musical chair quote came close to icon status (just google “Chuck Prince” and look at the suggested keyword strings), but Dimon’s over-performance compared to his peers in both good and bad makes him our overall winner of American Banking Icon.

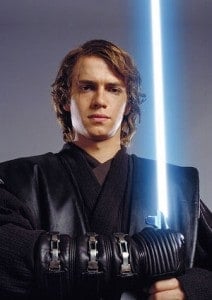

In the end, I feel about Dimon a bit like I feel about Anakin Skywalker at the end of six Star Wars Episodes. What a life! I admire the crisis years, keeping the JP Morgan ship afloat and soaring in the middle of the storm. I dislike the hubris and the missteps of the past couple of years. I’ve got the feeling that, like for Anakin – the passion, the torments, the bad acting of episodes 1 & 2 – it’s a package deal.

Dimon’s actions show that he surely is s shrewd guy, a gutsy guy. And his words tell us that he is both a smart guy and a proud kind of guy. I won’t be able to mention him to students as an all around exemplar of doing good and doing well, and that’s too bad because those kinds of guys are hard to come by to begin with.

Still, I’d be curious to meet Dimon on my next stroll on Park Avenue, and ask him about the past five years or so and his thinking about Pope Francis’ quote on the age of the golden calf. Maybe Dimon has learned a thing of two from overconfidence and lack of common sense, and can talk about gold blinding one’s vision. Maybe we could talk about what Catholic Social Teaching has to bring to finance, and vice versa. And certainly, it’d be fun to watch him and Francis talk, as one passionate, candid, and pragmatic man to another.

***

The cover image, by Flickr user vanderwal is available here.

— — // — —

- Here’s something against the split: http://www.nytimes.com/2013/05/09/opinion/the-jamie-dimon-witch-hunt.html?_r=0 and here’s a discussion about the notion with some of the actors involved in the vote: http://www.npr.org/2013/05/21/185686327/jpmorgan-shareholders-consider-splitting-ceo-chairman-jobs ↩

- See the “Merger Tree” here: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/JPMorgan_Chase ↩

- The uncovering of an agreement among many of the most powerful banks in the world to illegally fix the level of a benchmark interest rate used to value loans around the world: http://money.cnn.com/2012/07/03/investing/libor-interest-rate-faq/index.htm ↩