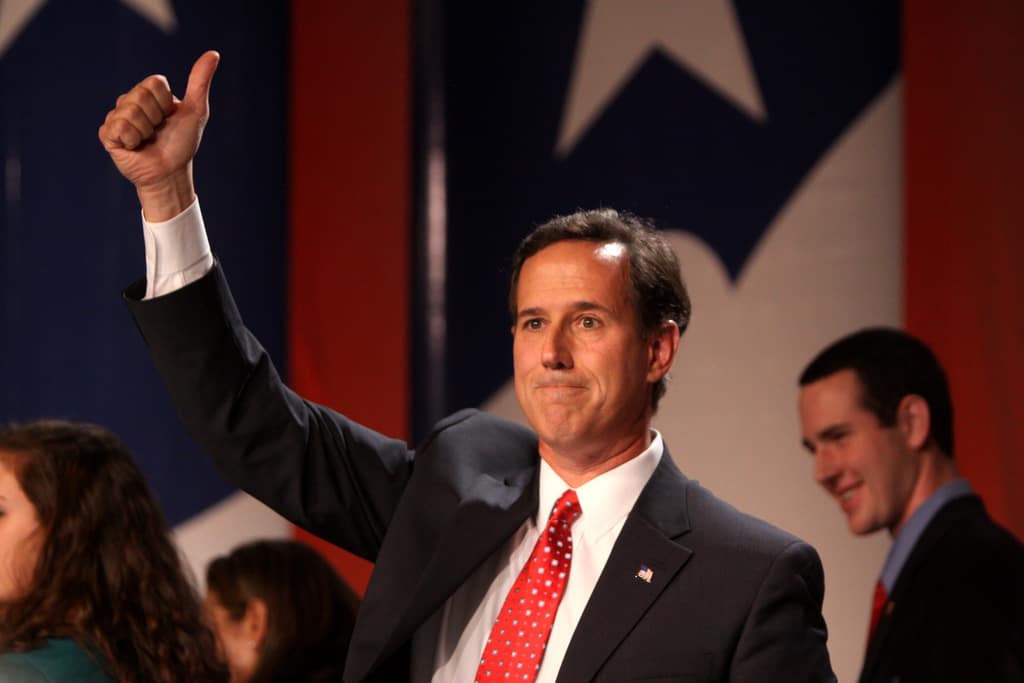

People lose their faith in college. Or so Senator Rick Santorum believes if his bold and intemperate statements of a few of weeks ago are taken at face value. As (yet another) Jesuit with too many degrees and who teaches at one of these colleges so maligned by Mr. Santorum (Santa Clara University in California), I’m sure it surprises no one that I respond negatively to such accusations. Yet there is evidence that he is right.

According to a 2006 survey by Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, 62% of college Republicans complained that religion is losing its influence on American life. Whether or not Mr. Santorum is adverting to this survey when he says that “62% of kids who go into college with a faith commitment leave without it” is unclear. If so, the senator’s claim exaggerates the issue. Far more significant, in my mind, is the statistic cited in Robert Putnam and David Campbell’s 2010 book American Grace: How Religion Divides and Unites Us. According to a General Social Survey, over the last forty years or so, the cohort of those young people who claim no religious affiliation has risen from barely 5% to roughly 25%.

Such statistics are telling. I’m just not sure how much they tell us. But if Mr. Santorum’s intention was to show that he could “feel the pain” of a demographic whose children don’t go to church, who disagree with the traditional values of their elders, and favor “being spiritual” over “being religious,” then he surely connected.

And he connected because there’s a familiar story here, one that goes something like this: parents love kid and kid grows up going to Church with parents. At 18 parents pay for kid to go off to high-priced college. Kid returns with a troubling disregard for what their parents hold sacred. Unpopular opinion alert: I’d be angry too if I had shelled out nearly $200K for my son or daughter to enjoy four years on some neatly manicured campus only to return and smirk when the family said grace before meals.

We should not be surprised that college is the context where such a turn often takes place. On that point I am fairly confident that Mr. Santorum is right. I’m just not sure it is helpful either to blame liberal professors or imply that the godless academy undermines religious values. Much less should we blame the students themselves!

In fact, I would argue that college is not only a place where young people lose faith. It’s also a place where they find it. Maybe the real problem is that this new found, college-influenced faith of the young looks a little different than what their parents were expecting. And that’s a familiar story for at least one reason: it’s mine.

***

In the spring of 1982 I graduated from St. Ignatius College Prep in San Francisco. A few months later I matriculated into Stanford University. As the product of 12 years of Catholic schooling, I was eager to attend one of the world’s finest universities and had the good fortune to be admitted into a program called Structured Liberal Education (or SLE, which folks on The Farm pronounced “slee“). It was a big, residence-based program build around the “Great Books.” As a freshman SLE was pretty much my only course, and it was presided over by a Marxist scholar of whom I (and all my classmates) were in awe. As I recall, many of the professors who taught in SLE wore their atheism as proudly as the fraternity guys wore their Greek letters. My professors, if not openly hostile to religion, often communicated a felt undercurrent of skepticism toward faith – it’s a tone and attitude that I have seen amongst some of my colleagues at the various universities I have attended and taught at as well.

While I cannot say that it was easy to have my beliefs questioned, debated, dissected before my eyes like a cadaver, I can say that the experience was purifying. It’s also impossible for me to say that attending Stanford induced the first faith crisis of my life. I had had many doubts, even radical ones, during my years of Catholic education. I had questions, deep questions, that neither catechisms nor priests were able to answer. I remember feeling at times that many good, pious people seemed unwilling to countenance my doubts, even downright frightened when I raised them as questions. At Stanford, however, my teachers often seemed only too willing to help me demythologize what I believed.

The irony is that, out of this experience, I heard God’s clear call to become a Jesuit. I remember the moment. I returned to my family’s home in San Francisco one April Saturday to attend the Easter Vigil, and at the very beginning of the service the presider announced that a beloved teacher of mine had died after a year-long battle with hepatitis. She was only in her thirties, and at the announcement of her death it seemed as if all the air was suddenly vacuumed from the room.

What struck me then and what stays with me now is how the presider faced the terrible challenge of proclaiming the core of our faith – Jesus’ resurrection – at the same occasion that we grieved the death of a beloved member of the community. Here we were at the awkward intersection of belief and disbelief, where no easy piety or standard wisdom could console. This was the place of faith: tense, uncertain, and strange. This is where I wanted to be my whole life.

And so I left Stanford later that same spring to enter the Society of Jesus. Moreover, it is within this same Society that I have come to know people, men and women, in whose faith I trust. If the souls of these trusted friends were landscape paintings, we would see in them an odd chiaroscuro where the lines between belief and unbelief are not always clear. They lead lives predicated on hope, not possession.

And at its best, that’s what faith is: a gift rooted in hope. It is not a possession. This is what I think of when I hear Mr. Santorum and others complain too loudly that young people lose their faith while in college. And I am not sure they understand what I mean.

***

A few years ago I met a distant cousin in Ireland. The state of the Catholic Church in Ireland these days is one of immense pain. Ecclesial authority there, as in other parts of the world, has suffered greatly from scandal, misuse of authority, and on and on. Many Irish priests speak of a loss of status, not to mention credibility.

When my cousin learned that I was both a priest and a professor at a Catholic school, he interjected that he could not imagine a more difficult job. “It must be impossible,” he said in his lilting accent. “How in heaven’s name do you make young people listen to you?”

And that’s where he missed the point, just there. You cannot make young people listen to you. If you want them to listen to you, you must first listen to them. Listen to their doubts, their fears, their pains.

You can impose on them neither an anti-religious, militantly secular point of view (as I felt my Stanford professors had done to me), nor an anti-secular, rigidly religious point of view (as Mr. Santorum and others might prefer). Rather, you respect their freedom, trusting that they have been created in God’s own image. And you trust that, if they have in fact been created in the image of God, that image will freely emerge. And soon, very soon in fact, you find yourself with them in that strange chiaroscuro landscape of faith.

I have been teaching now for almost twenty years, and despite my cousin’s worried questions, it’s not that hard. What people in their twenties want above all is people to trust, who are capacious enough to allow them to ask questions without fearing that answers will be shoved down their throats. Even so, they are looking for guidance. In fact, they are thirsting for guidance from people of intelligence and sensitivity, who have asked the hard, complex questions themselves with real discipline of mind. And often it is there that they find a faith not imposed, but discovered freely.

In fact, I appreciate Mr. Santorum’s lamenting of the fact that young people don’t find that place of faith often enough. But that is not because higher education is somehow antithetical to faith. Instead, it may be because there is no one there to hold their questions faithfully. Or it may rather be that our concept of what faith is is simply too brittle.