Spain is so well known for its meat and cheese that a request for plant-based food is a cause for astonishment and confusion. At a dinner in Montserrat, my waiter brought me cheese ravioli as the vegano option. When I said “no vaca leche por favor” in poor Spanish with animated hand gestures, the waiter thought I had some beef with cows and offered chicken instead. Eventually, after some back and forth, we communicated the essence of a plant-based diet. “Sola plantas?” he looked unconvinced, almost insulted. “Si, muchas gracias,” I nodded emphatically.

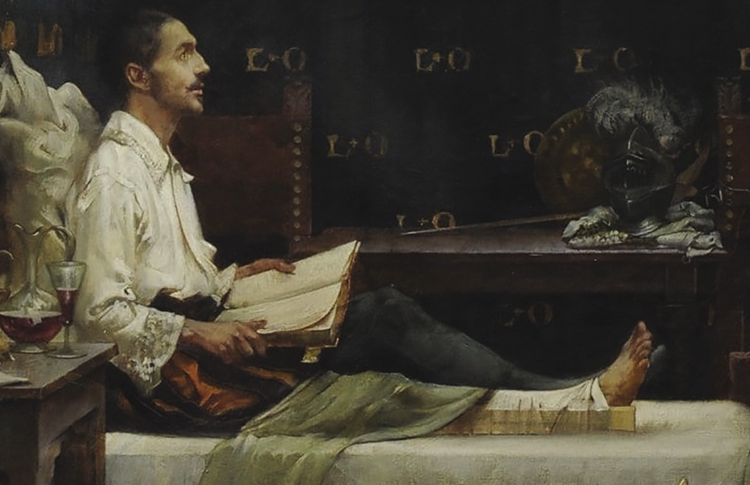

I was in Spain on a school trip that visited places associated with Saint Ignatius, a 16th-century Basque nobleman who gave up worldly possessions and aspirations to lead a pilgrim life in the hopes of serving God. Radical conversion is a much highlighted aspect of Ignatius’ life, with the Cannonball Moment being the most famous episode of the process of his conversion. During a battle, Ignatius was injured by a cannonball that led him to reflect on his life goals during a long convalescence, eventually leading to his conversion from worldly aspirations to heavenly ones.

In a sense, the moment of conversion seems to be the easier part. Suddenly, one hears God’s call anew that zaps us with a zeal to lead a new life. Bumps in the road ahead are beyond the horizon as one is fired up for the new mission of serving God. As I prayed in the Conversion Chapel at his family home where Ignatius recuperated for months, I wondered whether Ignatius had any inkling about what lay ahead.

My conversion to veganism had similarly been radical and had made me zealous for the cause. I had suddenly found a whole new avenue to live out Jesus’ teachings of mercy and compassion. To care for all of God’s creatures, I began shunning products associated with animal cruelty. But now a few years later, and in a foreign land, I was treading water in my conversion journey.

As I struggled with explaining the vegan diet in poor Spanish at the restaurant, I was painfully aware of the pitiful stares directed at me. I tried to lighten the situation with humor, hoping to shift the attention away from my dietary preference. After all, I had freely chosen a vegan lifestyle knowing well the occasional burdens it would entail. However, I was not distressed by having to eat three salads a day, or being served grilled asparagus as the main course, or being the odd one who burdens the waiter with unusual requests during a family-style meal.

What I found most difficult was to sit with people who did not share my concern for the animals that were raised in horrendous conditions and slaughtered mercilessly just for the sake of providing fleeting treats at dinner. Even the conversations at such meals centered around buying meat, cooking meat, and eating meat.

I could not escape from the meat theme and its connotations of cruelty to animals. I sat in silence, griping with God about my difficult situation. Why did God invite me to be compassionate to animals through a plant-based diet? Why wasn’t He surrounding me with a supportive group of companions, or perhaps even an admiring posse of followers? To my surprise, I found that following the story of the pilgrim Ignatius would help me navigate these difficult questions.

One of Ignatius’ first stops after his conversion was at a shrine dedicated to Our Lady of Arantzazu, a name that means “you among thorns” in the Basque language. What is often forgotten about Ignatius’ conversion story is the difficulties he faced in his post-conversion life. Ignatius imposed on himself a life of strict poverty, distributing his share of his family’s wealth and exchanging his fine clothes for a beggar’s sackcloth. His excessive asceticism led to medical issues from his refusal to eat food and drink water.

But that, I believe, was not the hardest part for the pilgrim. I believe the hardest part of his new life was when he was alone and unsure if his conversion was worth the trouble. Ignatius’ family tried to dissuade him, the Inquisition arrested him, and his early post-conversion companions deserted him. His original conviction of living in the Holy Land was thwarted by the political situation of the time. There were plenty of thorns along the path of following Christ. But he was convinced that serving God was worth every trial that came his way.

After more than a decade of false starts and persecutions, Ignatius found a band of friends who understood his mission to serve God in a new way. Until then, and even after that, he had to trust God that his way of discipleship was marked by truth, goodness, and meaning. He had to trust that God was inviting him to walk through the thorny path, first through loneliness, then through false accusations, and finally through the burdens of being the first superior of a new religious order. Over the years, Igantius may have reminisced about his youthful zeal after the Cannonball moment with a wry smile.

In a similar way, many who embark on vegan diets feel the same thorns as Igantius did. We are rejected as being impractical, misunderstood as self-righteous, and excluded from social situations to avoid awkwardness and inconvenience. Personally, I ponder the difficulty of sharing communal meals in Jesuit communities that do not share in my compassion for farm animals. Looking to the future, I wonder what it may be like to be a priest who declines meat dishes offered as hospitality by the people of God. However, in my uncertainty Saint Paul reminds me that “all things work for good for those who love God, who are called according to his purpose.” (Rom 8:28) I have to trust God’s call to the way of compassion.

Ignatius likewise had many questions about the future when he was traveling to Rome seeking papal approval for his new order. As he approached the city, he experienced a mystical vision at La Storta, just outside of Rome. La Storta means the curve, in this case connected with the bend in the road where the shrine is located. At this point, Ignatius did not know what the future held. And his vision of Christ carrying the cross may have filled him with some trepidation. But he was consoled that he was with Christ as he walked around the bend. A priest in our group preached that “we have to trust that the future is God-bearing.” When we cannot see around the bend, we trust that Jesus is with us and in front of us.

Ignatius’ trust in the Lord accompanying us into the unknown future resonates with Isaiah’s preaching on God’s holy mountain. When Isaiah preached about peace among all creatures (Isaiah 11:1-9), he didn’t know that twenty five centuries later people would still be wondering if peace between the wolf and the lamb would ever come to pass. Trusting in God’s timeline acknowledges His sovereignty over His creation. As His creatures, we are invited to do our part in building His kingdom on Earth even if we know neither the day nor the hour when God’s kingdom of peace will come to reign in its fullness.

One my last day in Spain, as I wandered the streets of Barcelona, I came across a tiny demonstration against factory farming. “Alleluia!” I said to myself and rushed to give them high fives. I thanked them for their witness, and encouraged them to continue their good work. They, in turn, encouraged me to keep up my activism and wished me well. When I described my difficulty in getting vegan food in Spain, they enthusiastically described the burgeoning vegan food scene in Barcelona, a food concept unheard of in the city at the turn of the century. We mused that perhaps sola plantas may become a standard order in restaurants someday!

It was just the tonic I needed after a tough week of traveling through Spain while feeling alone, misunderstood, and a little queasy after eating too much asparagus. Even in meat loving Spain, there were nascent signs of God’s kingdom of compassion for all His creatures. God was reminding me that conversion is not the end of the story. We must continue on the thorny path and unknown road, but God abides with us just like He had accompanied Ignatius five hundred years back.

Image: “Ignatius Convalesces at Loyola,” by Albert Chevallier-Tayler in St. Ignatius Church of the Sacred Heart in Wimbledon, England. (© Jesuit Institute)