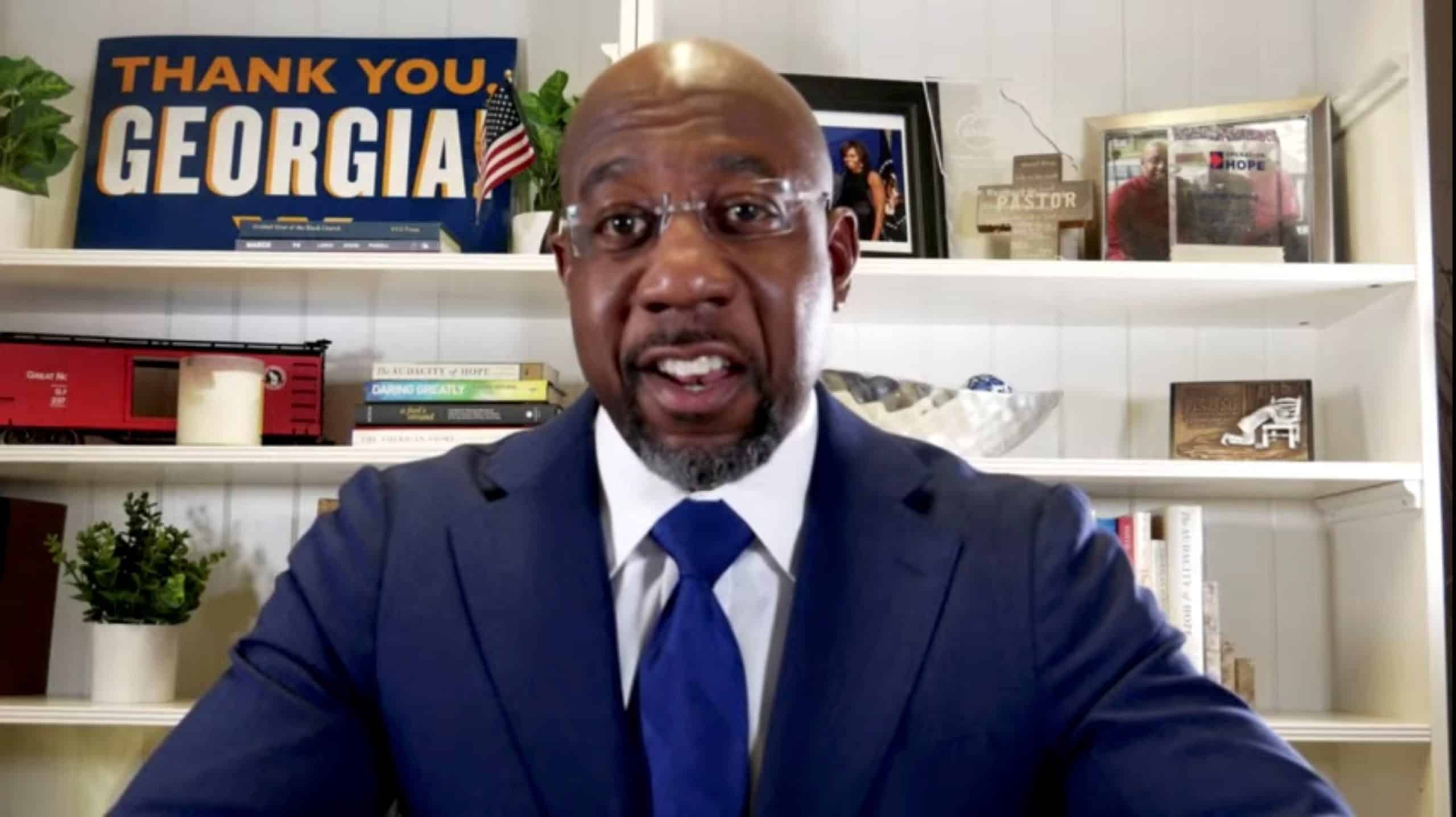

A day after Rev. Raphael Warnock won his seat in the US Senate, Christians stormed the Capitol with crosses and Jesus flags in hand. A day after a black man from Georgia defeated a white woman, insurrectionists waved and hung confederate flags in the halls of Congress. A day after this allegedly “socialist” Senate candidate was victorious, a rebel stormed the Hill with a sign that read, “The real invisible enemy is communism.”

The insurrection on January 6, 2021, was a nasty intersection of Christianity, racism, and capitalism, and it stands in stark contrast to the Christianity that Raphael Warnock represents, one informed by liberation theology.

The right-wing rebels who stormed the Capitol reminded us that Christianity can be used as a tool of unjust and baseless violence. Warnock’s liberation theology shows that there is a better way to be a Christian that doesn’t involve retreating from the public square. But what is this liberation theology, what is its approach to politics, and how does it oppose the false religion of the insurrectionists?

Liberation theology is a situated theology. It interprets the gospel from the vantage point of the oppressed, and it claims that God intended the gospel to be interpreted as such. God became human in Jesus to bring good news to the poor (Luke 4:18) and woe to the rich (Luke 6:24). Jesus preaches the liberation of the oppressed and asserts that his kingdom belongs to the poor (Luke 4:18, 6:20). The gospel disrupts the domination of the privileged.

A theology that separates religion and politics is a theology from the perspective of privilege. Liberation theologians, including Warnock in his book The Divided Mind of the Black Church: Theology, Piety, and Public Witness, point this out. A solely pietistic theology serves the interests of rich people and white people by preserving the political status quo. It quietly condones the active harm perpetrated by the religion of the militant right. However, a theology whose purpose is precisely to liberate people from all forms of oppression, including political oppression, not only serves the interests of the oppressed but also is truer to the gospel.

Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., launched the same criticism of apolitical, white Christians in his “Letter from a Birmingham Jail”. “I have watched white churchmen stand on the sideline and mouth pious irrelevancies and sanctimonious trivialities,” he wrote. Both Warnock and King lament white Christians whose eyes always look down at devotional books and never look up to see the violence against their black sisters and brothers around them. It’s not surprising that Warnock sounds a lot like King: they both served as pastors at the same Ebenezer Baptist Church in Georgia.

To be clear, however, Warnock also notes that liberation theology does not discard piety; rather, it addresses the whole human person, a unity of both spirit and body. Christ, who took human flesh, liberates not only the spirit but also the flesh. The church should do the same. Warnock states, “Authentic piety and true liberation are inextricably linked…the mission of the true church is to save bodies and souls.” In his theology, the flesh matters, and the flesh exists in history. Flesh inhabits a particular political space in relationship to other flesh.

There is no such thing as liberation theology in general. Liberation theology always exists in time and space. It exists in specific historical communities who seek their freedom. For black Christians in the United States, liberation has meant and continues to mean resistance to white supremacy. First, it was resistance to white supremacy institutionalized in enslavement. Now, it means resistance to white supremacy institutionalized in the police, in the capitalist economy, in voter suppression, and in many other power structures. Warnock writes, “The black church was born fighting for freedom, and freedom is indeed its only reason for being.” The church exists for the purpose of liberation, so, indeed, a church that does not fight for freedom is like salt that has lost its flavor (Matthew 5:13).

The Christianity that was on display during the invasion of the Capitol is not “good for anything” and should be “thrown out” (Matthew 5:13). Instead of a force for the liberation of the oppressed as Jesus intended, it is a tool of “white capitalistic forces”—that’s the expression Warnock uses to describe this false church in his book. Warnock’s mentor, James Cone, the father of academic black theology, takes this criticism further. He calls white nationalist Christianity “the Antichrist,” which is an appropriate term given that the New Testament speaks of “antichrists” emerging from within the church itself and denying the embodiment of Christ (2 John 1:7).

Warnock’s mission in Congress then—and ours—is similar to what the Capitol police ought to have done more rotundly on January 6th: expel white supremacists from the centers of power, including the Church, and preach a gospel that liberates the oppressed of all nations, not reinforces the passive piety of the privileged.

I pray that Rev. Warnock will bring his theology to Capitol Hill. I pray that he will enact policies that will free the United States from the bonds of greed and racism. I pray that he will use the newfound power of his office to liberate the oppressed.