Several of her bones were missing, still scattered somewhere in the Sonora desert. Her skeleton lay now in the morgue of the Chief Medical Examiner’s office in Tucson, Arizona. What confluence of circumstances pushed her farther into the desert to risk everything?

I asked this question in April 2019 on a week-long immersion trip to the US-Mexico border with a group of graduate students from Loyola Chicago. That examiner’s office was our first stop. Someone inquired: “Do any of their stories stick out to you?”

A momentary pause followed by: “Honestly, no. There are so many that all the stories start to blur together.”

His answer reminded me of something Margaret Regan, an author on immigration, had told our group the night before: “Migrant deaths have become so commonplace that journalists don’t talk about it anymore; it’s no longer news….These bodies get more care in the county morgue than when they were alive.”

Intense moments filled the week. We met with a variety of folks, from journalists and professors to religious sisters and border patrolmen.

We listened to migrants’ accounts of desert crossings and forced family separations. How poverty and violence propel their harrowing gauntlet northword, only to be stopped by an ever-expanding wall made of steel and anti-immigrant sentiment.

We learned about callous detention and deportation tactics and the devastating emotional costs for all involved.

We studied the dizzying constellation of inhumane policies that comprise immigration practice, their history and sponsorship by politicians both red and blue.

We heard about government suppression of sanctuary movements, the lengthy legal drama migrants face, and the threats to providing humanitarian aid. Jesus told his disciples to give a cup of cold water to his little ones (Mt 10:42). In the United States, you can be prosecuted for that.

Ash Wednesday happened to coincide with our visit to the U.S. Border Patrol. Smudged with ashes, our group sat at a large conference table and watched night footage of “drug dealers” attacking the USBP. A rock the size of two bowling balls headed the table.

“They hurled this at our vehicle,” said the patrolman. He pointed to the wall, where a menagerie of confiscated contraband meticulously framed a smashed USBP windshield.

The message was simple: These people are dangerous. I asked him how many crossings were drug related. Maybe 20-30%; most are people just trying to reunite with family. A confusing statement, considering the picture he had just painted.

Earlier in the week, we stopped at the Federal Courthouse to observe Operation Streamline, a program with a “zero-tolerance” approach to unauthorized border-crossings. It’s where undocumented migrants are prosecuted en masse, sometimes eighty people at once. I watched as migrants were shuffled into the courtroom, handcuffed and standing shoulder to shoulder – a grotesque assembly line of human bodies – waiting to be summarily sentenced by a court magistrate.

The last man “processed” pleaded repeatedly “Put me in jail, but please, my wife is pregnant with no money; can you send her milk and diapers? I made a terrible mistake coming here…I was desperate.”

Exasperated yet moved, the magistrate responded, “Sir, what you have to understand is that everyone comes for the same reason: out of social and economic desperation.”

* * * * *

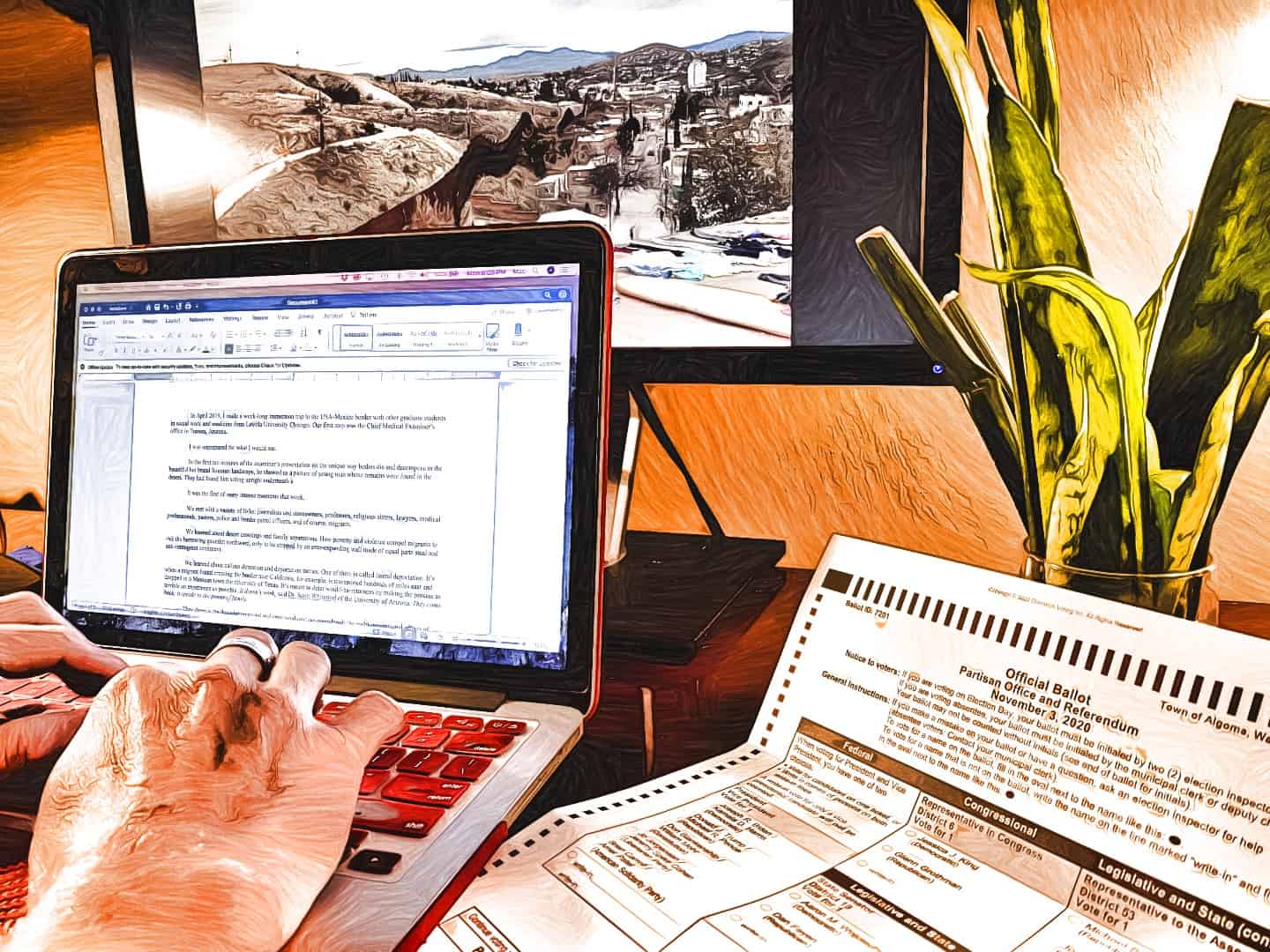

As I write this post, my absentee ballot is sitting next to me, still blank. There are Catholics who say the choice is simple. There is only one issue that matters. But those stories I heard suggest it is more complicated than that.

As I sit and discern my vote, I’m reminded of another experience. It happened a few weeks after we returned from Arizona.

I was at home in Chicago, in the middle of pouring myself a bowl of breakfast cereal when a picture from the medical examiner’s office flashed in my mind. It showed a young man whose body had been found in the desert. He was wearing jeans and a striped shirt. He sat upright on the ground underneath a rock outcropping, upon which a small tree had taken root. I imagine he stopped there to find shade. Did he know that is where he was going to die? His eyes were open, fixedly staring at the horizon, or as if on some dream that would never come to be.

At the breakfast table I began to weep. In that same moment, I recalled the lyrics of George Washington’s farewell song from the musical Hamilton; they had been haunting me for weeks. In it, Washington borrows a verse from the prophet Micah and sings:

I want to sit under my own vine and fig tree

A moment alone in the shade

At home in this nation we’ve made.Everyone shall sit under their own vine and fig tree

And no one shall make them afraid.

They’ll be safe in the nation we’ve made…(Micah 4:4)

To be with family, living in freedom, safe and secure. That was Micah’s desire. It was our first president’s desire. It was the desire of that young man who perished under that rock outcropping, and of all the migrants we met.

In these days of elections and fervent wishes, I add my own: that human suffering in all its forms will enter my heart and inform my conscience. That I might consider the myriad of issues at stake and carefully discern the complexities involved. That I might cast my vote for one who would reverence and defend not only the unborn, but those born anywhere, whose lives too are endangered by greed, indifference, and policies that strip people of their dignity.

-//-

Photo courtesy of the author.