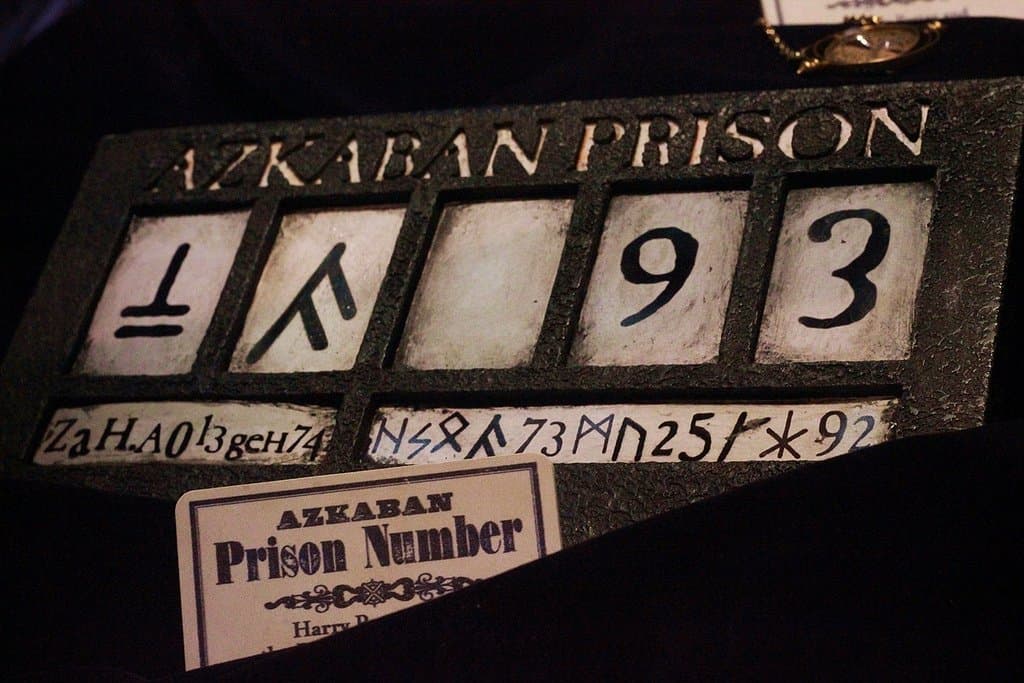

Growing up, my brother and I fought all the time. He played football; I sang soprano in the boys choir. He listened to as much gangsta rap as he could get his hands on, while I waited in line at midnight to get the latest Harry Potter book. I was a teacher’s pet where he was a regular in the principal’s office. His constant refrain was “you have no friends!” I would shout back “when they put you in jail, I’m not coming to visit!” He was the bullying cousin Dudley to my Harry Potter.

My brother has been in prison for most of the last five years. He was convicted on a minor drug charge soon after graduating from high school, and spiraled quickly into harder drugs as he found himself caught up in the Pennsylvania prison system. Driven by the thirst for profit, the commonwealth’s corporate prisons have fostered his dependence on the system so that their coffers might remain full. In particular, they regularly send him to solitary confinement for infractions that any outside observer would dismiss as a reasonable reaction to the toxic blend of addiction, loneliness, and helplessness that defines his daily existence. As a family, we share that helplessness with him, especially when the strictures of solitary confinement prevent even a phone call. We came to learn that the best way to communicate with a person so imprisoned is by sending books through Amazon.com.

Once my parents found out that we could send him books, they started a steady stream of reading material. From my dad, the latest crime fiction and sports history; from my mom, a grab bag of New York Times best-sellers. I got regular updates from them about his favorites–I think he’s read the entire John Grisham back catalog at this point. I was shocked to find out, then, that he had started to read Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire. I was flabbergasted to hear that he had devoured it. He asked my parents to send along the rest and quickly became attached to the characters to whom I had turned for refuge as a child. He couldn’t believe he had ignored these stories for so long.

As a Jesuit novice, my funds were severely limited so I couldn’t participate in the de facto book-of-the-week club with my parents. I wanted to help, though, so I outsourced my contribution. I emailed a group of close friends, citing their many offers to help over the years. I told them what he’d liked so far and encouraged them to pass on something they thought he would like. Because he was still in solitary confinement, we assumed the books arriving, but had no way of knowing for sure. Finally, his attorney managed to get a visit in. They talked for hours and she emerged with messages for each of us. I received an email from her that said “Tell Jake to let all his friends know how much he loves all the books. He was overwhelmed.”

Despite the years of claiming I wouldn’t, I visited my brother when travelling home last summer. Due to his unpredictable moves and my restricted novitiate schedule, we hadn’t seen each other in over 18 months. He looked different: taller, happier even. I noticed him before he noticed me because his eyesight has gotten so poor (maybe from all that reading). I bought him a cheeseburger from the vending machine (I declined one for myself) and begged him to tell me what I’d been wondering for months. What had he thought of Harry Potter? Who was his favorite character? What house did he think he was in?

In that stark fluorescent light, my brother entered the world that for so many years had been my refuge from him. He mourned for Professor Dumbledore, he got excited about the Triwizard Tournament, he sorted himself into Slytherin house. He told me about his attachment to Neville, the sad sack who emerges as a hero. And in that dingy waiting room, over a revolting microwaveable cheeseburger, we reconciled. We laughed in a brotherly way that had eluded us for our first 24 years together. We reminisced about our least favorite teacher, and fretted about our youngest brother’s progress in school. He told me about his defense of scrawny new prisoners, and I told him about how I’d been sent to help seventh-graders study for vocab tests. It was refreshingly normal.

The Bible is littered with stories of brothers at odds: Cain and Abel, the Prodigal Son and his scornful brother, plus Joseph and David and their respective broods. Consistently, God works through fraternal animosity to accomplish something greater. Stark contrasts in character lead to moments of surprising grace. For most of my life, I’ve tried to distance myself from my brother’s embarrassing behavior. But despite my best efforts, God brought us back together.

A few weeks after my visit, we both got cell phones again for the first time in two years. He moved to a halfway house; I moved to Chicago to study philosophy. We could finally text, his preferred method of communication. I quickly fell back into my role as type-A, bossy older brother. “What are you reading?” “Are you writing anything?” “Have you gone to SoulCycle yet?” (I was convinced that SoulCycle was the solution to everything.) He responded in his typical fashion: one word answers, plus occasional meandering phone calls in which he complained about boredom and worried about the prevalence of drugs in the state-run halfway house. And so we talked. The long-standing animosity between us seemed to have melted away. We were able to chat without the weight of years of fighting burdening us.

One day I snuck out of Mass to take his call. “I made a mistake,” he said. The immediate freedom of the halfway house had been too much for him and he had relapsed. “I think they’re going to send me back to solitary confinement,” he said. “Can you call mom and dad and let them know. I’m so sorry. I know I let everyone down. I know mom and dad are probably going to cut me off this time.” This moment had happened many times before, such is the nature of addiction. But never before had he chosen to confide in me. The newfound connection I felt had clearly meant something to him to.

In a moment I can only attribute to grace, I felt momentarily released from the bossy older brotherly-ness that is my default with him. I didn’t feel even the slightest urge to chide him. “I’m so sorry this happened,” I said. “We love you and we just want you to get better. I’ll have my friends send books. Have you read The Hunger Games?”

***

Image courtesy FlickrCC user Leticia Smania Donanzan.